It’s January in Southern California, and I’m in shorts and a T-shirt sitting outside and talking on the phone to Joe Bussard. He is speaking to me from his home in Frederick, Maryland, where it’s about 10 degrees outside. Every so often, he asks me to excuse him while he runs out to turn over a steak he’s grilling. Outside. In freezing East Coat winter weather. But that’s typical for Joe – he does what he wants to do, no matter the circumstances.

Joe Bussard is probably the most celebrated record collector this side of Dr. Demento. Unlike the good Doctor, who is a very shy, retiring fellow when not in character, Bussard is loud, opinionated, dismissive and not very flexible in any way I can name. He’s one of those guys who think Louis Armstrong lost his fastball by 1929. In the course of this particular conversation, he’s already torn into Elvis, Merle Haggard, every Louvin Brothers record on Capitol, Chet Atkins and anyone who opposes the war with Iraq.

I let these slide. But writing off Armstrong’s post-Hot Five career? This will not stand. I come back at Bussard because anyone with enough sense to wait until summer to fire up the grill also knows that Louis Armstrong had a second peak in the late 1940s, which lasted about 10 years and culminated with the masterpiece Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy. And I let Joe know it in no uncertain terms. I fire at him with everything I’ve got. Joe doesn’t exactly back down, but he makes an allowance in my case, recognizing that I’m pure of heart.

“You may be right,” he says, “but you gotta excuse me. What’s the word? I’m feeling adamant today.”

Not that Bussard is ever anything less. A visit to his MySpace (!) page–maintained by his son-in-law–gives you an idea. He’s like the “thumbs up/thumbs down” restaurant critic character Paul Wilson played on Curb Your Enthusiasm: a walking yay or nay on everything under the sun. (His fierceness actually reminds me of Ted Nugent.) Bussard is right at home making loaded statements designed to either provoke you or sort you out from the riffraff. His political non-correctness is only rivaled by that of Charlie Louvin.

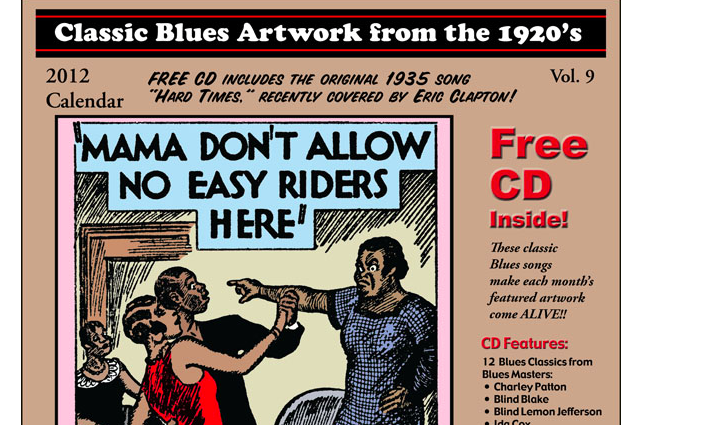

On the other hand, he’s the keeper of a certain impolite segment of Americana. Bussard boasts an immense record collection that tells the tale of pre-1950 American colloquial music. His musical world is populated with cowboys and Cajuns, blues singers and banjo-picking farmers, string bands and jazz bands, singing brakemen and medicine-show hucksters. Those in the know say that the Bussard collection is not just huge, but that everything in it is the good stuff, in amazing condition. And unlike a few dog-in-the-manger collectors, he makes his records available to interested parties.

Dedicated readers of liner notes may have noticed Bussard’s name on such notable collections as the Smithsonian/Folkways reissue of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music; Old Hat’s marvelous collection of medicine-show musicians, Good for What Ails You; and Revenant’s magisterial Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues by Charley Patton. This is because he lets anthology compilers raid his collection, which in many cases contains the only known copy of a particularly choice musical tidbit.

Bussard also hosts a handful of radio shows for local stations between Knoxville and Frederick, all in an attempt to spread the word about the music he loves. His theme, “The Lost Child” by the Stripling Brothers, is almost a manifesto for Bussard. It’s an archaic, anarchic fiddle tune played by Charlie and Ira Stripling, two brothers from Pickens County in western Alabama for whom the Louvin Brothers were allegedly named. “The Lost Child” opens the Old Hat CD Down in the Basement, a compilation of Joe Bussard’s favorite records.

“That’s an interesting CD,” says acclaimed roots musician Dave Alvin, who’s no stranger to record collecting. “It gives you a sense of what it was like for [guys our age] in the world before downloading, when you had to go find collectors who had these records that you had heard of or read about. And, if they were enthusiastic like Joe, they’d play you these old records that maybe didn’t sound old to you, and they’d just kind of teach you about this music and change your world.”

Joe Bussard is best known as a collector, but not many people know that he ran his own label, dubbed Fonotone, from the late 1950s to the late 1960s. Bussard ran it out of his basement record room in Frederick. He recorded people and cut – on his own cutting lathe – his own 78 rpm lacquer records. In 2006, Dust to Digital collected Fonotone’s output in an elegant box set, which was nominated for a Grammy … but not in a category that pleased Bussard.

“They nominated the box it came in!” he grouses. “With all that shit they give awards to, they should have nominated it for the music, and it shoulda won ‘cause every song on it is better’n anything they give a goddamn award to.”

Bussard’s objections aside, the box is a wonder and consists of five discs, a 160-page booklet, postcards of recording sessions, a Fonotone bottle opener and some cool paper ephemera, all housed in a cigar box. Fonotone is such a Bussardian creation: a local, hometown, one-man label whose output was almost entirely jug band, acoustic blues and bluegrass music. Fonotone never issued LPs or 45s, just 78s with homemade labels. That it ever existed is a testament to one man’s dissatisfaction with whatever was in the marketplace. Bussard gave the recording artists, most of whom were his buddies, very 1930s-string-band-sounding names like the Tennessee Mess Arounders and the Possum Holler Boys. That Fonotone lasted so long with so little monetary reward is proof that Bussard is, well, adamant.

Bussard made records of himself playing guitar with his band, the Georgia Jokers, and with Bob Coltman in the duo the Guitar Rascals. He also played the jug in Jolly Joe’s Jug Band. Fonotone was more than a vanity project, though, and scored more than a few coups. Fonotone was the first label, for example, to record John Fahey, who used the name Blind Thomas. Stefan Grossman made his first record there as Kid Future. Even Mike Seeger did a session for Bussard, using the name Birmingham Bill because he was under contract to Folkways. (Seeger’s recordings were payment for a bunch of tapes he’d made from Joe’s collection.) Bussard also recorded artists like Clarence Fross, an old, black banjo player he discovered on a record-buying trip, and a number of local fiddlers and guitar pickers who played the old-time tunes in the old-time way.

Fonotone is, forgive the hyperbole, the coolest thing I ever heard of, and when I found out there was such a thing and that it was being anthologized, I ran out and bought that box and listened to it straight through in one sitting. It about knocked me off my pins. Some of it was remarkable and worthy of the kind of overstated praise one might find in a teen mag like Spin (a very aptly named publication); some of it was merely great, some just very good, but every one of those tracks had something.

Just what is it about Joe Bussard that pulled magic out of these artists? Whatever it is, it seemed to work on all kinds of musicians–from legends in the making like Fahey or Seeger to some local cat whose career pinnacle was exactly that sole Fonotone recording. So, I decided to see Fonotone up close and experience, firsthand, what it’s like to be recorded by Joe Bussard.

Frederick, Maryland, is a lovely, old, small city in imminent danger of McMansion Expansion. Pre-World War II stone houses are still pretty usual there, but they no longer dominate the local landscape. Civil War buffs are well-acquainted with the area.

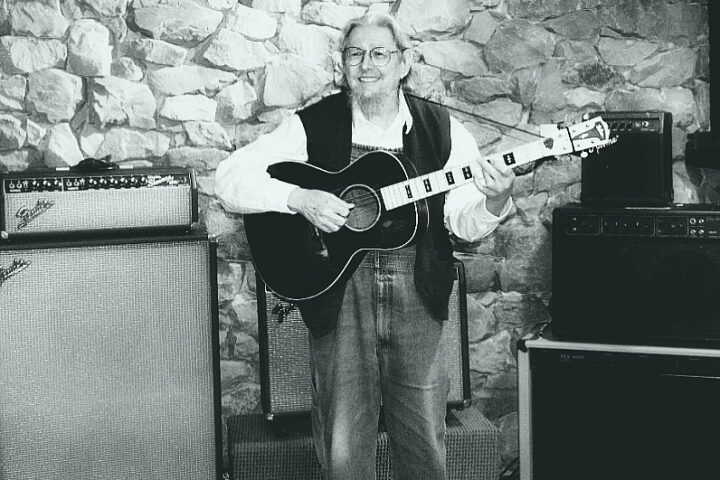

Joe Bussard’s house is off a main road, and he sees us coming and greets us in street clothes and battered black bedroom slippers. He wastes no time bringing us down to the record room, at which point he turns into an iPod on Dexedrine. As he plays each record, you can’t help but notice how well he knows it. He mimes every instrument as it solos, sings along, laughs louder than hell at every good lick and has another record cued up and going before the previous one hits the run-out groove. Each record gets louder than the last. (His love of sheer volume is apparently another value he shares with Ted Nugent.)

Bussard’s wisdom comes at you at about a mile a minute. He’s collected in excess of 15,000 78s and seems to have listened to them all, remembering every fine point of each one. And he wants to let you know it.

“One time, I found bunches of old records on the Montgomery Ward label,” he says, recalling one of the countless record-finding excursions he’s made over the years. “And I was in heaven, with all these great old Carter Family sides. And they’d be all played and beat to hell. Then you’d see a couple of really clean records, and you’d play them, and they’d be shit, just some bullshit dance band that wasn’t nothing. And you didn’t have to wonder why they looked unplayed after you heard ‘em once. I just wonder why they’d buy ‘em in the first place.

“Another time, I went to a house once in the middle of … oh, hell, I don’t even know if the damn place was on a map, but they had all these Paramounts there, and this was the local distributor for Paramount. And we found some records that day! You bet!”

He breaks into a laugh that is equal parts mischief and everything that ever had love for the world.

This is also the room where Joe Bussard produced every Fonotone session (with one microphone) and cut every copy of every record the label put out, complete with hand-typed labels. The typewriter is still there (there’s no computer), as are the reel-to-reel decks, but the lathe is in dry dock. The cheapest price among collectors on an original Fonotone is about $200, which is not an unreasonable ask given that each is a handmade artifact.

“Those were the days, I tell ya!” Bussard says enthusiastically. “We’d just go and go and go, one take! And ever’ record we made sounded like it, too!”

The range of records he plays for us that day is staggering. Novices may lump prewar music into a big, amorphous category (sort of like the way people lump cantors, klezmer and Israeli psych bands into something called “Jewish music”). Yet, Joe Bussard sees every record differently.

“The Depression really changed everything up in music, not for the better,” he explains. “There never was a period for recording music in this country or the world anything as good as what was in the ‘20s. You had families and brothers playin’ together, jazz was– well, it was jazz, and I don’t know what you call that stuff now, but it ain’t jazz. There were those beautiful tones. It was a much more inspired time, wide open.”

As if to underscore his point, we’re listening to Jimmie Rodgers’ “Blue Yodel #9” as Bussard speaks. Not only does Rodgers stake out his territory as the finest country singer who ever lived, but he’s backed quite ably by pianist Lil Hardin and her husband, trumpet man Louis Armstrong. You can just feel everyone playing on the very edge of the music, and it really does feel wide open.

If Bussard has a North Star above all other musicians, it is surely Rodgers. “The first time somebody gave me some records, there was a couple of Jimmie Rodgers’ in there, and I’d never, ever heard a voice like that. He’s the greatest I ever heard.”

(That rapid-fire crunching together of syllables, the disregard for tense, is true Bussardian English, in exactly the way that first-person present tense is Damon Runyon’s English. It’s not grammatical confusion at work: For Joe Bussard, this music is fast and alive and rolling as sure as it tumbles out of that huge speaker in the corner of his basement. He hits hard consonant syllables and short words with the alacrity of a tap-and-die. The once omnipresent cigar is no longer in evidence, and I don’t have the heart to ask if or why he gave up tobacco. )

Everything that looks even remotely like a shelf has records (or Edison cylinders) on it, kept in a careful order known only to Joe. Every ledge has a typewritten sticker that says “please do not touch records.” His system is seemingly foolproof, as he never has to look for a record. He just reaches and – voila – it’s that rarest of all birds, “Original Stack O’Lee Blues” by Long Cleve Reed and Little Harvey Hull on the Black Patti label, probably the most elusive of all commercially issued records. The specimen is pristine, the famed gold peacock against a black background. He holds it but lets me run a finger across the label, which is smooth and shiny. This record is rare enough that it could put your kid through his first year of college.

“You know what I been offered for that record?” he asks. “I could get 40,000 for that record with one phone call, if I wanted. Hell, I’ll never sell it. No way.”

He pulls out some test pressings from the old Gennett label, tracks the legendary Ernest Stoneman cut on sessions that were never issued because of a dispute between the temperamental Stoneman and Gennett label honcho Ezra Wickemeyer – or perhaps Fred Gennett himself. (Bussard is unclear on the matter – his words spill too fast to soak up, and his syntax is largely based around visual aids, starting with whatever record he’s got in his hand.) His basement is full of striking visual treats, from Jimmie Rodgers memorabilia to an Edison cylinder player, a cat and the original Harry Smith LPs.

He looks down at the instrument cases that mandolinist Tom Eaton and I have with us and asks, “Well, y’all wanna pick something or what?” He sets up an old (but not quite vintage) mic for the two of us, and we start into “Katy Cline.” Joe comes to life the way he came to life when he played us the Stripling Brothers record. He hits the record button and says, “Now!” Joe plays air guitar with me, mouths the words, strums an invisible mandolin, wags his head back and forth and pats the heel of his bedroom slipper in time with every beat. Tom and I are playing to a stadium crowd of one man. He’s 20,000 Zippo lighters at once, and we are Live at Budokan, Double Live Gonzo and Intensities in 10 Cities – right under his nose. He points at us, as if he’s finally made eye contact. He seems genuinely thrilled.

Joe Bussard has an interesting theory: Musical forms seem to lose their value when the electric bass is introduced. “That goddamn electric bass ruined everything!” he shouts. “I went to Trashville – I mean Nashville – in ‘57 to see the Opry, and I asked for my money back, I’ll tell you that right now. They didn’t have shit I wanted to hear. Garbage! When rock come in, I didn’t have any interest in anything that damn dumb! Elvis and all that bullshit! I already knew better than to fall for that, buncha gooddam shit for retarded 4-year-old kids!”

He considers Jimmy Murphy’s RCA records to be the last (non-bluegrass) records of any value to come out of Nashville. (Don’t worry, I’d barely heard of Jimmy Murphy myself.) One listen to Murphy’s “Big Mama Blues” is a step back to the kind of whipsnort unleashed by the Stripling Brothers or any number of old string bands. On the other hand – and Joe is not gonna like this – Murphy sounds like a backwoods rockabilly with professionalism. He’s a man apart from any time period; the closest comparison is Harmonica Frank, who cut for Sun. Neither performer had a hell of a lot to do with his peers or the marketplace. Depending on who you ask, each man’s respective style was either too far ahead of the rockabilly curve or 10 years too late for all-acoustic hillbilly boogie.

Everyone – not least of all Chet Atkins – thought Murphy had the elusive “it.” But stardom never lifted her skirt to Jimmy Murphy (I know I stole that phrase from Nick Tosches, but what a phrase), and he never got to quit his job as a bricklayer. In 1978, he was rediscovered and made an excellent album, Electricity, for the then-new Sugar Hill label. While its success was modest, it was success nonetheless, and when Murphy died in 1981, he was likely happy that he’d be remembered for something other than his masonry.

“Big Mama Blues” is a work of greatness, but on its face, its strengths are its commercial liabilities. It really does bring back the instrumental sound of an earlier time. It rocks hard. I mean, the damn thing screams, but it screams like Wayne Raney, not Little Richard. It is as relevant to its time as legwarmers are to 2007.

When Joe Bussard is gone, that’ll be it for his kind. No one today has quite the same world view – absolutely defined by records – that he has. Richard Spottswood and Henry Sapoznik each outscore Bussard in terms of reissue production and traditional scholarship. As for Robert Crumb, well, Crumb is Crumb, and it’s not his main forte to be anything else, although he too has done some impressive reissue work. But Crumb’s records will be relegated to a footnote in his legacy; he will always be known as the man who elevated comics to fine art.

And Joe? Joe Bussard is, like “The Dude” in The Big Lebowski, not exactly a hero, but the right man for his time. Except that time stands still in Joe’s basement.

Leaving Joe’s house – coming up from the basement into the brisk Maryland afternoon – was like leaving a movie matinee. Your eyes readjust to natural light. We all went to Joe’s favorite place to eat, a local coffee shop called Barbara Fritchie’s, immortalized in Desperate Man Blues, a documentary about Bussard.

“WegetchagoodcuppacoffeeaBitchie’s,” he fires, almost in a single syllable. He tops it off with a huge smile and another big laugh at the nickname he’d imposed on the restaurant. The coffee was excellent.

I hopped a Greyhound to Philly, and as Maryland morphed undetectably into Delaware, I thought of a passage from an article that Gay Talese wrote for Esquire in late 1965, called “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”:

He is a piece of our past – but only we have aged, he hasn’t . . . we are dogged by domesticity, he isn’t . . . we have compunctions, he doesn’t. . . it is our fault, not his. . . .

Joe Bussard is not a Sinatra fan, but I’m sure he would recognize his own life and his own wisdom in those words.

This article originally appeared in the Fretboard Journal #8.