The Avett Brothers’ Seth Avett is a prototypical little brother–sweet, affable and earnest, if a bit in his own world. He relaxes into the couch and watches as his big brother, Scott, intensely present and engaged, does most of the talking. Seth is prone to pondering the meaning of things, while Scott talks about making things work: the songs, the shows, the career.

In conversation, they support one another, finishing each other’s sentences and nodding as the other speaks. There is no hint of ego, tension or competition. It’s a peaceful, authentic balance of energies that is immediately and viscerally appealing. There would be something special about them even if they never made music together.

But they do. For all intents and purposes, they always have.

In their college years, the brothers played in separate rock bands. Seth was in a band called Margo in Charlotte, North Carolina, where he went to school. Scott was in a band called Nemo in Greenville, doing “a lot more screaming, and even some new-metal rap,” as he once told Raleigh’s Metro Magazine. Eventually, the bands merged under the name Nemo and started gigging around the state toward the end of the 1990s.

On Tuesday nights, they began attending jam sessions affectionately known as Nemo Downstairs, an all-acoustic revue with a rotating cast of players. They weren’t particularly into roots music; to this day, they cite Hall & Oates, Alice in Chains, the Pixies and hip-hop as formative influences. Nonetheless, Scott picked up the banjo. “It was out of irony,” he explained to Billboard. “I couldn’t have chosen a more opposite instrument to who I was or what I was into at that time. It was strange going into bluegrass. I didn’t grow up listening to that stuff. I was into rock music and metal and stuff like Prince.”

The irony wore off, but the songs stuck around. Just before Nemo fell apart, in 2001, Scott and Seth, with the band’s guitarist, John Twomey, put out a self-titled EP of high, lonesome country harmonies as the Avett Brothers. The following year, they replaced Twomey with upright bassist Bob Crawford and never looked back. It’s been nearly 10 years since then–with 200 days a year on the road and around 2,000 shows altogether.

“We really like to say yes,” says Scott, in his light drawl. “We always like to keep it in the forward motion.”

Chickens in the Yard

Roots music wasn’t entirely new to the Avetts. They grew up in rural North Carolina, with chickens in the yard; their grandfather was a preacher, and their grandmother played piano in church. Their father, Jim, an accomplished songwriter and musician in his own right, played Hank Williams, Tom T. Hall and Appalachian folk around the house.

What the Avetts found in their turn to acoustic music wasn’t so much a particular style as a way to sing more honest, personal songs. “If someone is standing 10 feet away talking to you on a bullhorn,” Crawford told the Vancouver Sun,“sure, you can understand what they’re saying. But if they’re standing next to you and whispering in your ear, it’s more intimate. And that’s what acoustic music does, essentially.”

Leaving the Marshall stacks behind was liberating. With lighter gear came mobility, spontaneity and less distance between the band and their audiences. They focused on crafting simple, openhearted songs and delivering them with unrestrained energy. The banjo-guitar-upright sound evoked old-time country and bluegrass, but the Avetts were never traditionalists or speed-picking virtuosos. Their early albums contain more than a few off-key notes and pitchy harmonies, but they got over on deeply personal lyrics and unerring melodic instincts. Their priorities are no different now.

“Still the main thing to us is the spirit of it,” says Seth. “The songwriting is always at the forefront; it’s always what matters the most to us. But I think sort of haphazardly, we’re getting better at our instruments.”

The early disregard for technique led to a few awkward moments, like one particular show at South Carolina’s Winthrop University. “We were circled around,” Scott recalls. “We had our hands in, we were going to get ourselves charged up, and as we’re doing it, they say, ‘The Avett Brothers!’ We turn around and we’re onstage. Nothing’s in tune, nothing’s plugged up. That show had long lulls where I’m standing there, tuning one string on one of the old [Gibson] B-25s–it just wouldn’t happen. Every string was out of tune, they’re waiting, you’re getting ready to do a song that you don’t really know . . .”

“And it’s not like one of the other guys is up on the mic, saying something clever,” Seth adds. “We’re all just standing there.”

The lack of traditionalism has at times gotten them in trouble with purists, as with an infamous early appearance at the International Bluegrass Music Association Awards.

“We were obnoxious when we went there,” Scott admits. “We set up in a lobby that was full of bluegrass groups kind of jamming. You don’t pay attention to one band there; it’s a group thing. But we were there trying to carve this path. We misunderstood what the IBMAs really were, and [realized] that we weren’t proper bluegrass.

“Nowadays, we wouldn’t dare disrespect what they were doing. We’d say, ‘Man, this is great! We don’t belong here doing that.’”

Both brothers learned piano as kids, and then guitar. To this day, they do their initial songwriting on piano, and Scott, to the chagrin of dogmatists, still plays his banjo like a guitar, flailing and whacking at it with manic abandon.

“I was taught traditional three-finger style–Scruggs-style–from a fellow named Ned Mullis of the Mullis family, which taught Seth and I how to play piano and guitar as well,” Scott notes. “They’re Piedmont musicians, intertwined with Arthur Smith, who wrote the ‘Dueling Banjos.’ But from there, the finger style just mutated and has changed to deliver the energy I try to deliver through my songs.”

Getting that energy isn’t easy on their instruments–the band is known for breaking dozens of strings per set. To absorb the abuse, Scott has always been a fan of Deering banjos. He bought his first Deering Sierra in the summer of 2001 and has had it ever since, accompanied now by a Black Diamond, a Tenbrooks and a Deluxe. Recently, they’ve been joined by a couple of Stellings–a Crusader and a Staghorn.

“The Deerings,” says Scott, “have just proven to be workhorses; they continue to get me through the shows. The Stellings are a bit more graceful and a bit more detailed and elegant instruments, and tend to serve other purposes. I’m very fond of the company and their philosophy.”

Up until a few years ago, Seth played mainly Martin D-35 and HD-35 dreadnoughts, but recently he found his perfect guitar, through sheer serendipity.

“This buddy of mine in Canada is named Jordan McConnell, a guitar player in a band [the Duhks] we’re friends with,” he explains. “Just by happenstance, I was in a hotel room with him and some friends, and there was a guitar sitting over on the side. I picked it up and started playing it, and I was like, ‘My God, what kind of guitar is this? This is incredible.’ And he’s like, ‘Oh, I built that.’

“At that moment, I started scheming and trying to figure out how I could get him to build me some guitars. I couldn’t really put it into words; it’s just exactly what I like. It’s loud; it’s very, very bold; the action is not really low and not really high. You just know when you got a natural fit.”

Bob Crawford, who was learning upright bass just as Scott was learning banjo–both of them making up in enthusiasm what they lacked in chops–also found resilience an issue.

“In the first four years of the band, we were very, very aggressive–always aggressive,” he acknowledges. “I had a Chinese carved bass, a more expensive classical bass, and I was destroying it. We would go out on the road for a week or two, and I would come back with these long cracks in it. I took it to a luthier, and he said, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing to it.’ So I got a plywood Engelhardt/Kay C1 in 2005, and I have beat the heck out of it. It always stays in tune and has responded very well to the abuse. It’s definitely held up on the road.”

Projection

The combination of traditional instruments and punk-rock energy has always been the band’s calling card. They wanted to be heard and remembered, and to do that at those early house parties and street fairs, they had to be loud. In some ways, it’s a habit they’ve had to break.

“We played a lot of outdoor, mic-yourself scenarios,” Scott offers, “and getting the crowd for us demanded a lot of volume and a lot of energy. Projection was key. It’s almost like Broadway singers: We got on the streets and just projected, projected. When you’re live on the street, tone is the last thing you need to worry about; you just need to get the crowd. Banjo, as an instrument, is a great tool for that, because it is very abrasive and very loud, and guitar helps set up a platform.

“We got so into going to these shows and just flailing and going at it, all of a sudden you find yourself at times going, ‘Oh, this isn’t working.’ We’ve always wanted many levels and layers in our show, and for that to happen, you have to be able to bring the sweetness to it. That’s tone and quietness, which amplification allows you to do with acoustic instruments as well.”

Early on, the Avett Brothers were a ramshackle acoustic three-piece aiming for rock grandeur; they were channeling songs with multiple parts, timeless themes and instantly memorable choruses through a low-fi filter. In recent years, they have become a full-on band. In addition to Joe Kwon, who plays a 1998 Peter Staszel cello, they’ve now picked up a full-time touring drummer, Jacob Edwards. They’ve even mixed in a couple of electric guitars, including a Guild S-100 and a Fender Telecaster. Grandeur has come within reach.

By their fifth album, Emotionalism, the early tension between street-performer spontaneity and rock classicism had begun to resolve itself–decisively in favor of the latter. Do they worry about losing that scrappy, seat-of-the-pants attitude? What will happen without those fortuitous mistakes?

“I don’t think we ever need to worry about not making mistakes,” Seth laughs. “Between each record, you’re looking at a few hundred shows. That’s bound to change how you approach your instrument. It’s bound to change, God willing, how well you play your instrument, how well you sing the notes. Some of the rawness and scrappiness will stay there as long as our enthusiasm is there for the music. But as far as the rawness of making mistakes and letting it go, that would be about as likely as going back in time. Some of the things I let go back then, I just can’t imagine letting it go now.”

Adds Scott: “We try to recognize when it works and when it doesn’t. We just aren’t willing anymore to allow it to pass without our critical thinking toward it. You can’t ever go back.”

“You can’t go back,” Seth quickly agrees. “If you taste every kind of root beer, you’ll find out what root beer you love and the reasons you love it, and then you just want that root beer.”

Root beer? That must be the Carolina coming out of you, I tell them.

Seth: “Let me choose a more universal example: barbecue.”

Scott: “Of course! Everybody knows barbecue.”

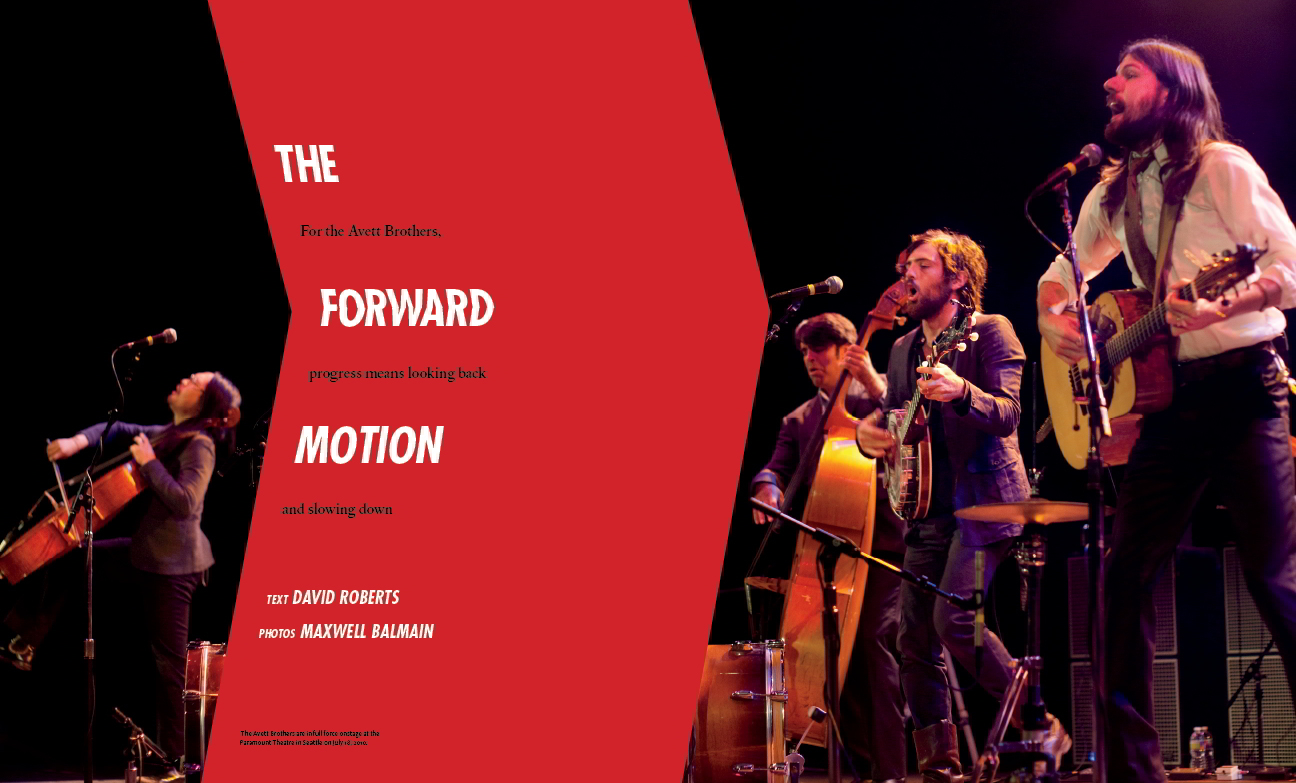

Photograph by Maxwell Balmain

The band is unlikely ever to return to the intimacy of its early shows. The team, the tour and the crowds are all getting bigger. The guys can no longer hang out after shows until every hand has been shaken and every autograph signed, as they did in the early years. Seth has said that the title track on I and Love and You, their most recent studio album, is in part about the growing distance between the band and its fans: The highway sets the traveler’s stage, all exits look the same.

“We operate as a unit more now,” says Scott. “And as a unit, we communicate more on a public level, through our songs. So our topics in songs may have become broader–to cover a broader message.”

From the beginning, Avett fans have responded to the message with exuberance–dancing, clapping, crying and singing along. “An Avett crowd is one of the best crowds to play,” frequent opener Langhorne Slim told American Songwriter. “That’s a fact.” It’s not a jam-band scene; there is no permanent convoy of stoners and grilled-cheese vendors following the tour. Aside from the occasional T-shirt, there aren’t even any particular tribal markers. But there is always a sizable contingent of what they call “Team Avett” at the shows, and it’s easy to spot them. They are, in a word, happy. Beaming.

Plenty of artists lend themselves to intense emotional identification, but when the songs are directed at young people, the message is, typically, “I understand your pain and heartbreak, and I’m miserable, too.” The Avett Brothers don’t tiptoe around pain and struggle, but they refuse to be miserable. They speak to their fans’ hopes and aspirations as well as their regrets, their pride as well as their doubts, in a cynical, media-saturated age when few others are doing so (outside of corporate marketing departments).

That sense of uplift may help explain why the audiences are so diverse in age and subculture, why there are older people and young parents with kids dancing among the hipsters and neo-hippies. A study of Avett crowds always reveals a strong undercurrent of personal affection and admiration; the band and their fans really seem to like each other. There’s a sense of family.

Family is at the core of the Avetts’ music. The last track on their third full-length studio album, Mignonette, “Salvation Song,” is as close as any band comes to a mission statement:

We came for salvation,

We came for family,

We came for all that’s good,

That’s how we’ll walk away.

We came to break the bad,

We came to cheer the sad,

We came to leave behind the world a better way.

What the Avett Brothers make is, in an almost pre-modern way, family music: music to be sung aloud, together. (A quick YouTube search reveals a treasure trove of small children singing their songs.) There is struggle in the songs, sometimes humor, sometimes anger, but there is no hint of ironic distance. There’s no hiding behind sunglasses or personas, no mumbled lyrics. The Avetts are almost unnervingly honest and plainspoken.

Such wholesome sentiments can be easy to mock. It takes confidence to be so vulnerable, a sense of self-possession that the brothers had from the very beginning, thanks to their upbringing in a tight-knit blue-collar family. Jim and Susie Avett have been married for almost 40 years and still live on the same small farm in Concord, North Carolina, where the boys were raised. (Both brothers, now married with kids, still live nearby.)

“My daddy, he had nine kids, and we loved one another. I grew up in that atmosphere,” Jim Avett told Magnet. “We tried to create that in our house. Scott and Seth love one another.” At the end of A Carolina Jubilee, the band’s second album, is a track called “Home Recordings,” made by the Avetts in 1985, when Seth was 5 and Scott 9. (“9 3/4!” he protests on the scratchy tape.) It’s only a brief fragment, but it’s a clear window into the steady, affectionate role Jim played in the kids’ lives.

“People say to me, ‘You must be so proud of them,’” he snorts. “I’m no more proud of them when they make music than when they’re making hay for the cows. If they’d never been musicians, we wouldn’t love them any less.”

It was Jim that ultimately encouraged them to bet on the band. “Play it the way you play it,” he told them, “and if it’s entertaining, then folks will come to hear you. If not, then we’ll sit here on the front porch and entertain ourselves.”

Purpose

It’s clear the brothers have spent their lives living up to the example their father set. Early albums contain plenty of songs about romantic and alcoholic misadventures, but there was always an undercurrent of purpose. The most frequent recurring theme in their music is growing up–working through the anxieties and temptations of youth to become good men. Contemporary commercial culture tends to represent masculinity as a kind of testosterone-soaked infantilism, wherein to be manly is to drive fuel-inefficient cars and get laid by blank-faced models.

The Avett Brothers sing about an older conception of manhood, one that’s about living up to responsibilities, being there for family and doing one’s best. Sings Scott in “Ill with Want”:

Free is not your right to choose,

It’s answering what’s asked of you,

To give the love you find until it’s gone.

In “A Gift for Melody Anne,” Seth sings:

I just want my life to be true,

I just want my heart to be true,

I just want my words to be true,

I want my soul to feel brand new.

Part of being a grown man is knowing how to treat a woman, and the brothers have made something of a specialty of the heart-on-the-sleeve serenade. The Avetts sing about the fairer sex with something like reverence. “Keep your clothes on,” Scott sings, memorably, in “Laundry Room,” “I’ve got all that I can take.” That guileless sentiment, perhaps the only recorded instance in pop-music history of a female being asked not to disrobe, tends to elicit an audible sigh from audiences exhausted by the insistent sexualizing and objectification of women in popular culture. Another frequent Avett subject that rarely makes an appearance on the Billboard charts: marriage and kids.

The powerful sense of family that has shaped the band has carried through in their professional life as well, where they’ve built a tight-knit crew of family and friends to run the operation. Manager Dolph Ramseur has been with the band since 2003 (he’s still operating on the handshake agreement they made back then) and has helped them build an old-fashioned career. It’s been slow and steady growth from the beginning, gig by gig, fan by fan, fueled by sweat equity and word-of-mouth marketing. It wasn’t planned that way; it just happened.

“In hindsight,” Scott reflects, “the good thing we’ve done–and we didn’t have any clue–was just not concern ourselves with success on day one, or year one, or even year four. If you want to write songs and play songs, start today doing it. And do it again tomorrow.”

“There’s no expiration date,” Seth continues. “It’s really attractive when you’re 19 or 20 to think that you’ve got to be like Cobain or Hendrix or something. Like your 20s is the only time to do it. But look at Clint Eastwood.”

“Willie Nelson,” Scott interjects.

“Look at Willie Nelson,” Seth agrees. “There’s no expiration date. Everybody’s going to mature, emotionally and professionally, in a different timeframe. If you’re not on the cover of Fretboard Journal by the time you’re 25, it’s all right.”

“That’s really hard to avoid when you’re young,” Scott adds.

“We had those thoughts,” Seth confesses, “but at some point, you get too old to have them. You have to believe that you can still do something, otherwise…”

Scott: “You got nothing.”

Seth: “You got nothing.”

Photograph by Maxwell Balmain

In 2007, Ramseur’s label, Ramseur Records, released the band’s breakthrough album, Emotionalism. That record and the tour behind it put the band on the national radar and brought them to the attention of legendary producer Rick Rubin.

“As soon as I heard the depth in their singing and songwriting, I was in for the ride,” Rubin said. “It’s unusual to hear such openhearted personal sentiment from young artists today.” He asked the band to come meet him at his home; they hit it off, and he brought them onto his Columbia imprint American Recordings to produce last year’s I and Love and You.

Longtime fans were openly anxious that Rubin would sand down the band’s edges for a mass audience. But to hear the band tell it, Rubin’s only directive was to slow down, experiment more and be patient about finding what the songs need. It was the brothers themselves that had a revelation early in the recording process. As Scott told Independent Weekly: “For the past five years, you hear, ‘Man, I love your records, but live it’s really awesome.’ So you immediately start thinking, ‘We gotta get the records like the live, with that energy.’ Forget about it. It’s not the point. The next day, we woke up and shifted everything and kind of embraced the idea that the record will always be a different thing.”

The studio work with Rubin yielded the band’s most crisp and refined music to date. The abrasive banjo of old gave way to swelling piano, strings and drums. Country and bluegrass largely gave way to a stylistic kaleidoscope of rock, pop, boogie and balladry (sometimes in the same song). It is exquisitely crafted music, poignant and often sublime, though some fans found the new sound almost too crafted, too clean and crystalline, as though the songs would shatter if treated roughly. Those concerns have been overcome as the band has played the songs live, where they’ve been loosened up and filled out into full-blooded rockers.

In many respects, the Rubin magic worked: The album sold well, and the band was launched onto a circuit they’d never accessed, one made available by major-label resources. There were TV soundtracks, late-night shows, music videos and opening slots for gargantuan touring acts like John Mayer and the Dave Matthews Band. Some 10 years into their career, they were introduced to a mass audience.

In the iTunes era, when every new band is instantly hyped, instantly available everywhere and just as instantly gone, the Avett Brothers are still forging those personal connections, fan by fan. Somewhere, a kid at Wal-Mart just found I and Love and You and is setting out on a journey back through a dozen albums and EPs–exploring a little corner of the overcrowded media universe he didn’t know existed, a little corner that feels like it was made just for him.

Postscript: Street Signs

On a sunny July afternoon in Seattle, the Avett Brothers graciously deliver a private acoustic performance in front of the Paramount Theatre. “What’s the first song you ever learned to play together?” they are asked. Scott squints for a second, glances at Seth and says softly, “Well, this is one we’ve known all our lives.” They sit down on the sidewalk, lean back against the wall, close their eyes and play the first chords of “Signs,” a song their father wrote and recorded in the early 1970s. As the song gets going, they slip right back into street-performance mode–projecting, projecting, getting the crowd. Pedestrians begin to gather. Over to the side, Bob Crawford taps his foot and grins like a kid on Christmas–like he couldn’t believe his luck.

After the applause is over and the crowd disperses, the band gathers their instruments and heads back down the sidewalk toward the tour bus. Before they are out of sight, they are at it again, the four of them, strumming and singing as they walk, still playing every chance they get, still keeping it in the forward motion. – David Roberts