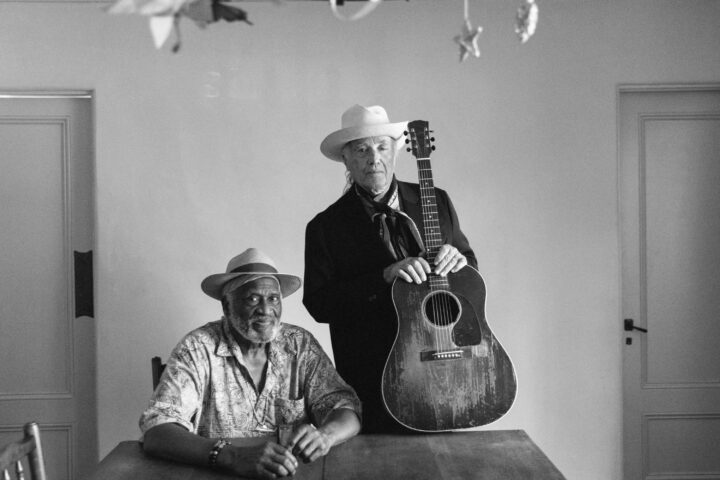

[Editor’s Note: The following is a brief excerpt from the lengthy Ry Cooder interview contained in our forthcoming Fretboard Journal Electric Guitar Annual (shipping in late August 2018). Pre-order your copy here.]

“No more snare drums,” Ry Cooder sighs. That’s the dictate Joachim Cooder gave to his father. Ry’s Gear Acquisition Syndrome hasn’t slowed down, and his son would like him to apply the brakes.“I’m his curator,” Ry explains and then adds, with all the parental pride one can muster, “Get this—I got him a set of Elvin Jones’s hi-hat and ride cymbal!”

We’re sitting in the music room of Cooder’s Santa Monica home. It is exactly how you’d imagine it. Cramped with cases, vintage Fender and Standel amps, drums (Joachim may have a point), weird Japanese guitars and, leaning lazily on a rack, two of the most iconic instruments recorded since the ’60s: Ry’s two, endlessly copied, never-quite-finished Fender Stratocasters.

It’s a bit of a mess right now, something the 71-year-old guitar hero simply shrugs off. “I’m a one-man shop. I don’t have little guys who come in at night like elves and take care of things for me. My wife says, ‘Can’t you get an assistant?’ I said, ‘What do I tell them to do? It’s all me.’”

During the time of my visit, Cooder had just unveiled one of his finest albums ever, 2018’s The Prodigal Son. It’s filled largely with gospel and bluegrass tunes that Cooder has transformed into his own thanks to his usual stellar guitar playing, some great vocal work and incredible percussion accompaniment from Joachim. It’s a triumph. The problem at hand now, on the day of our talk, was how Ry could re-create the damn thing on the road. As we sort through his gear, old and new, during this interview, Cooder is cracking jokes, describing how the album came to be, and most importantly, calculating just how many flight cases he would need to custom order.

Fretboard Journal: Based on the material found on the new record, I have to ask: Have you found religion?

Ry Cooder: Yeah, they said I would be asked that. I’ll put it this way. It’s 2018. In 2015, Joachim and I went on tour with Ricky Skaggs and the Whites. We’re going to do quartet singing and country songs, so we spent about a year—Joachim and I would fly to Nashville and rehearse with them once a month—it took about a year to get that repertoire together. I found that the most interesting of all the songs, just Hank Snow, Hank Williams, but the best fun is the gospel songs, because they’re the most rousing, I guess you could say the most involving. You get into it. That’s what it’s all about, that music. You feel it. I’d always liked it.

It’s what got me interested in bluegrass when I was in high school. And I went and got a banjo back then, I was going to learn banjo and play the music. But it didn’t work out, I didn’t end up doing it. But I had learned all those songs and I knew them, I had memorized them all. I used to think the bass part is the most interesting, that’s the fun stuff. I don’t have a bass range or anything, but when we were rehearsing they said, “Well, sing down there. It sounds good,” because they all sing up high. The sisters and Ricky, they’re all tenor singers.

We got going on this, and then as we went along the highway, doing shows, I said, “You know, you guys want me to sing this Hank Snow song or this Lester Flatt song.” I said, “I don’t have any business singing this stuff. I don’t think I can pull it off.”

“Oh yes, we like it. We like your sound on that, so go ahead, do it.” I said, “Yeah, I just don’t know. I don’t think I’m there.” And they said, “No, do it.”

“Okay.”

So, I persevered and I kept doing it, and especially singing the quartet stuff. By the end of the tour, I had gotten to where I began to think, “This is okay.” I used to shy away from that. I used to sneak “Jesus on the Mainline” or something onto one of these records, for all these years, some [Blind] Alfred Reed tune…just to have a little extra fun without making a big deal out of it. It was just there.

I also would say that I always remember the audience liked it—they would respond to these tunes. [The songs] have a lot of traction or something. It’s very appealing music, naturally. People wouldn’t have been drawn to it through the years if it had been boring. It’s anything but.

By the end of the tour, then I thought, “Well, you know what? I’m going to think again about doing these tunes. At my age and station, who’s to say it’s wrong? I’m just going to give this some serious thought.” And then Joachim came and said, “It’s time to make your own record.” You could see the audience was there, they liked what you’re doing. That tune “You Must Unload” was the one that the people would go crazy for, they’d stand up.

I said, “Well, okay. Should I be singing this stuff? You mean, make a solo record?” I said to him, “Make a solo record of that kind of material?” He said, “Yeah, if you like, it play it. Just play it. You don’t have to worry about accordions and banda horn players and whatnot. And forget about politics.” He said, “That’s hopeless. It’s no good. It’s a lost cause. You’ve done all that.” I said, “Yeah, I agree with you.” It hurt my back, I used to get so mad. My acupuncture doctor said, “No more of that stuff.” She was Chinese, she was very strict.

Then I thought, Okay, but I’m not the Singing Rambos. I’m not going to be able to do that the way it was done. Or the Stanley Brothers or the Foggy Mountain Quartet. We don’t have that here in Santa Monica. And it really doesn’t exist. Ricky [Scaggs] and the Whites are kind of it, in terms of quality. In terms of living in that world and growing up with that music, and being that. But when you’re from Santa Monica, everybody talks about, “Uncle Billy Bob taught me how to do this, and sang in church.” And as I always say, there’re no uncles in Santa Monica to speak of. There isn’t that lineage and that DNA here. It just doesn’t exist.

This is strictly a backwards ball cap, Range Rover town. Although, it used to be an aircraft worker town. Those people were transplanted boarder Southerners and did like Merle Travis and so forth, but that world is long gone. That’s the Kash Buk world. Joachim said, “No more Kash Buk.” He goes, “You did that. You can’t keep going down that road.” He said, “People don’t know what that’s all about. Skip it. Just sing these good tunes that you like to play and we’ll do it.”

That was the initial thought to the record. Gospel music, yes. Simple music, beautiful, I really love it very much. Then one day I came in here and Joachim was here, sitting with his tracks on the screen, and he had this little watery kind of fluid dapple light effect sound that he was working with, that he had created. And I said, “Is that a new song of yours? Is that something you’ve got lyrics to or something?” He says, “No, I’m just fooling with it.” Then I said, “Well, can I borrow it, because ‘Straight Street’ will go right over top of that easily.” “Straight Street” by the Pilgrim Travelers was a real flat-footed walking rhythm gospel tune from the ’50s.

If you’re smart, you don’t say, “I will be the new Pilgrim Travelers.” It’s not going to happen. And for that matter, African-American people today don’t sing like that, either. Nobody does, or almost nobody. More about that later. I said, “But I can resing, I can redo ‘Straight Street.’ The lyrics are good. And this thing that you’re doing,” I told him, “suggests this kind of a slightly more ambient, easy way of doing the song. It’s not shouting and stamping, and it’s certainly not Mavis and Pops [Staples]. It’s more in my hands, something I can do.”

So, I did that. We took the track out to the engineer’s house, I sat there and put earphones on and sang it, and then played the guitar at the same time. I said, “That’s good. That’s an idea. Let me do some more like that.” So there were other tunes on the record that were done in that way, and it was encouraging and I could see this is fun and I like it. Then we said, “Well, let’s cut some live stuff.” So we did that too, in the studio.

Also, based with a playback of these ambient tracks of his also in there, giving us something to just surf along the top of. So you don’t have to do everything from just brutal scratch. That’s hard, because it gets to the point where you just don’t know anymore. “I just don’t know. What’s the right thing to do?” You know what I mean? “Do I like this groove? Do I like that groove? Do I like this key? Do I like this other key?” I just can’t take that and it’s too much, it’s too hard. But he already has the key, then, with the playback.

It’s a nice key, he’s figured this out. He’s sensitive to keys. “Harbor of Love” is the best example of that on the record. That song is light years away from Carter [Stanley]’s original, which was 3/4 time. Now it’s vaguely in 4/4 time. But it gave me some place to occupy, to sit there. So, back to your question about religion: It doesn’t really have too much to do with religion. It’s just the songs that I like, that I feel … What’s the word I want? I’m not sure what the word is. But it is a long-time thing. I’ve known these tunes for a real long time. And I’ve always liked them through the years, decade-in, decade-out.

“Harbor of Love” is the perfect example. The lyrics are good. Carter Stanley was a great songwriter, in that back-porch style of his. He’s not a Nashville pro. He wasn’t. Wherever he had come up, through church or his mountain man experience, he was able to really compress it into something. He had a lot of good tunes. Funny, sometimes, and terribly sad… “Mother’s Not Dead.” Did he write that? I’m not sure. I think he did. It’s like, “Whoa, what a brain up there.” It isn’t something I grew up with, like Ricky did from birth, in the house, in the community, in the village. Church on Sunday? Nothing like that here. This is, as I say, a ball-capper town. An artisan, olive oil town. Whatever people are into.

It’s not a question of faith for me or anything like that. I’m strictly just outside the tribes. I’m not a tribe member of any tribe. But I like to play this stuff and sing it. Now it’s been so many years of trying to make records, and learning to do that…it takes a lifetime. To learn to play and sing something that’s good, I guess. Unless you’re born into it like, say, Ira Louvin. God help you, but if you are Ira, it’s a tough road. But you could be that great in that one particular way that he was very great.

But we of Santa Monica can never do that. That could never happen.