In the summer of 1957, comedian Phyllis Diller was forced at the last minute to cancel a weeklong booking at San Francisco’s Purple Onion nightclub. Frank Werber, a talent agent who had an office above the venue, saw this as a perfect opportunity for the new act he had just signed to get some much needed stage experience. He persuaded the Purple Onion to give the slot to his group, the Kingston Trio.

That first week went very well and the Kingston Trio—Bob Shane, Nick Reynolds and Dave Guard—were asked to stay on for another week, and then another, and then another. Eventually, their one-week trial booking stretched from June until December. During that time, word about the Trio’s powerful singing and hilarious stage patter made its way down south to Los Angeles. Various music industry figures, and the occasional movie star, made the trek north to San Francisco to check out what the fuss was all about. Voyle Gilmore, a producer at Capitol records, liked what he heard and signed them to a contract. In February 1958 the Kingston Trio recorded their first LP. One song off that LP, “Tom Dooley,” became a massive hit and immediately made the Kingston Trio the most sought-after musical act in America.

For the next few years, the Kingston Trio toured relentlessly, playing on college campuses and in nightclubs across the country. From 1958 to 1964 (the year they left Capitol records), they had played thousands of shows and had released 19 LPs, five of which made it to the top spot on the Billboard charts. The Kingston Trio brought the urban folk revival into the mainstream of American popular culture and made Martin guitars and long-necked banjos must-have items for musicians everywhere.

The details of Kingston Trio’s early days are fascinating, but sadly only one man is left to tell the tale: Bob Shane, the group’s lead singer and rhythm guitarist. Dave Guard, the trio’s banjo player, died in 1991 and Nick Reynolds, the group’s tenor guitarist and percussionist, died in 2008. John Stewart, who replaced Dave Guard in 1961, died in 2008; Frank Werber, the Trio’s manager, died in 2007; and Voyle Gilmore, their producer at Capitol Records, died in 1979.

Bob Shane is now retired from performing. In 2004, shortly after his 70th birthday, he suffered a major heart attack. He now lives in Arizona, where he oversees the Kingston Trio’s business interests. I was very excited to have the opportunity to talk to him. My mother had quite a few Kingston Trio records when I was growing up, as well as records by performers who followed in their wake such as the Limeliters and the Chad Mitchell Trio. She really liked the music, but she had a soft spot for the Kingston Trio because in 1956, when she was a teenager, Dave Guard pulled her out of a wrecked car.

I wanted to talk to Bob Shane about the early days of the Kingston Trio. When I called him for this story, I was pleased to discover that he had been thinking quite a bit about that period himself. The roots of the Kingston Trio go back to the early 1950s, to the Punahou School in Honolulu, Hawaii, where fellow students Bob Shane and Dave Guard first met. Shane, who had started out on ukulele years before switching to tenor guitar and later six-string guitar, taught Guard a few chords and they began working out a few songs. “We played and sang Hawaiian music and mellow music,” Shane recalls. “We also liked Tahitian music because it was more up-tempo than Hawaiian music. We also sang a couple of songs from Samoa. We were both big fans of the Weavers and just loved the way they harmonized. We weren’t great guitar players, but it didn’t really matter because all we wanted to do was sing harmony.”

After graduating from high school, the two friends headed east to California, where Guard enrolled at Stanford to study economics and Shane got into nearby Menlo College, where he enrolled in the business administration program. At Menlo Shane met Nick Reynolds, a hotel management major from Southern California who grew up in a musical household. According to legend, Reynolds first noticed Shane sleeping during an accounting class and figured that was a guy he had to get to know. They two students quickly discovered that Shane’s baritone and Reynolds’ tenor blended beautifully and, more importantly at the time, that their singing got them invited to the best parties. “And by best parties, I mean the ones with the best booze and the prettiest girls,” Shane clarifies.

Shane introduced Reynolds to Guard and they began performing together at frat parties and local beer gardens as Dave Guard and the Calypsonians, sometimes as a trio or occasionally with other friends. At the time, calypso music was extremely popular, and the group played songs like “Jamaica Farwell” and “Come Back, Liza” that Harry Belafonte, the reigning king of calypso, hade made popular.

In 1956 Shane graduated and moved back to Hawaii to work in his family’s sporting goods business. During that time, he worked up a solo act and got a regular gig at the Pearl City Tavern in Honolulu. “I did a few different things like singing Harry Belafonte and Hank Williams songs, but what most people don’t know is I was the first Elvis Presley impersonator in the world,” Shane says. “I was billed as Hawaii’s Elvis Presley in 1956, which was the same year he got really popular. It was a great idea because they didn’t have much television in Hawaii yet, so you could do whatever you wanted. I had sideburns and I wore a bright sport coat and stuff like that. And I’ll never forget when I met Elvis in ’63, just briefly, and I told him that’s how I got my start. And he said, ‘What did you want to do that for?’ That’s exactly the way he said it. That’s the only thing I ever said to him.”

While Shane was in Hawaii, Reynolds and Guard continued to perform in the Bay Area. They joined up with Menlo College student Joe Gannon, who played rudimentary bass, and singer Barbara Bogue. They refashioned themselves as the Kingston Quartet (they maintained their link to calypso music by naming themselves after the capital of Jamaica) and tried to get jobs at various local nightspots, but they had little success. The struggling quartet crossed paths with publicist and talent agent Frank Werber, who liked them but felt that Gannon’s bass playing wasn’t good enough. When he suggested he might sign them on if they got rid of Gannon, Bogue said she would leave the group if Gannon was kicked out—so they did, and then she did. (Gannon later went on to have a successful career as a stage designer for acts like Neil Diamond and Alice Cooper. He and Bogue eventually married.)

Guard and Reynolds called Bob Shane in Hawaii, who was finding life in the family sporting goods business uninspiring. And although he was doing pretty well as a solo performer, he really missed singing in harmony. In March 1957 he came back to California to join the now-renamed Kingston Trio under the management of Frank Werber. On June 25, Werber got them the weeklong gig at the Purple Onion that later stretched to a seven-month residence. After the weeks stretched on, it dawned on Werber and the Trio that they didn’t have enough material, so they began a relentless search for new tunes.

Some of the songs they came up with dated back to Shane and Guard’s days in Hawaii. Selections like the Tahitian medley “Tanga Tika/Toerau” and the Hawaiian tune “Lei Pakalana” made it into their stage act and later appeared on various LPs, while others, such as the Samoan song “Minoi Minoi,” didn’t make the cut. “Run Joe,” which Guard used to sing with the Calypsonions, was in the act for a while, but was never recorded. “Truly Fair,” a song Shane learned in 1951 and sang during his Hawaiian Elvis days, was tried out, but it was found wanting and dropped from the act.

From the beginning, the Kingston Trio decided to avoid protest songs and material with a political bent. The Weavers, who were a major influence on Shane and Guard, had their careers ended because of the entertainment blacklist during the McCarthy Era. The Trio considered themselves entertainers and not activists, and felt that protest songs didn’t fit into their act. Over the years, the more politically oriented part of the folk music community would use this decision as one of their main complaints about the group.

Two of the band’s most famous songs showed up under fairly mysterious circumstances. The first, a jazzy barroom ballad called “Scotch and Soda,” was brought in by Dave Guard, and it was perfectly suited to Shane’s slightly raspy baritone. Guard was dating a girl named Katie Seaver (the older sister of baseball great Tom Seaver), and her parents taught him the song. The Seavers first heard it in a hotel lounge when they were on their honeymoon in Phoenix, Arizona, in 1935; they had the piano player write the lyrics and melody down so they would always remember it. Sadly, the piano player neglected to write down his name, and to this day no one knows who actually composed the song.

Furthermore, nobody in the Trio could recount how they happened to learn their most famous song, “Tom Dooley.” It was a failing that had legal repercussions later on (see sidebar). Reynolds once said they first heard the song when a now-forgotten singer sang it during an audition at the Purple Onion. Shane thinks they learned from an LP by the Tarriers, the New York-based group that featured Erik Darling, Bob Carey and soon-to-be actor Alan Arkin. The Tarriers were best known for writing “The Banana Boat Song,” which became a huge hit for Harry Belafonte under the name “Day-O.”)

In 2010, Shane was cleaning out a closet and found a box of old reel-to-reel tapes that the Trio made in 1957 during their initial stand at the Purple Onion. “We would record our songs on a Wollensak tape recorder so we could go home and learn our parts,” he explains. “At the time, none of us could read music, and this was the best way of doing that. There was a storeroom above the Purple Onion and we would spend our days up there rehearsing, five and six hours at a time, and then go downstairs in the evening to perform. We really worked our butts off working on our act.”

Shane remembers the makeshift rehearsal studio as being particularly grimy. “Have you heard about the huge dust cloud we had here in Phoenix?” he asks. “It was like a mile high and a hundred miles wide. It looked like the Black Death was coming at you. It completely blacked out the airport to the point where they had to cancel all of the flights. And when it finally left, it left a whole lot of dirt around. That’s what it was like upstairs above the Purple Onion. It was really dusty.”

Werber would watch each performance and keep careful track of what songs went over well and which ones flopped, which bits of stage patter received the most laughter and where in the show the energy flagged. As the months dragged on, Werber and the Trio found they were getting a good response from the folk songs the group sang, so they began to add more to the act. “We weren’t folksingers,” Shane stresses. “We were an act that did some folk-oriented material. From the beginning we also did stuff like ‘They Call the Wind Maria,’ which was a Lerner and Lowe song from Broadway, but people don’t remember that.”

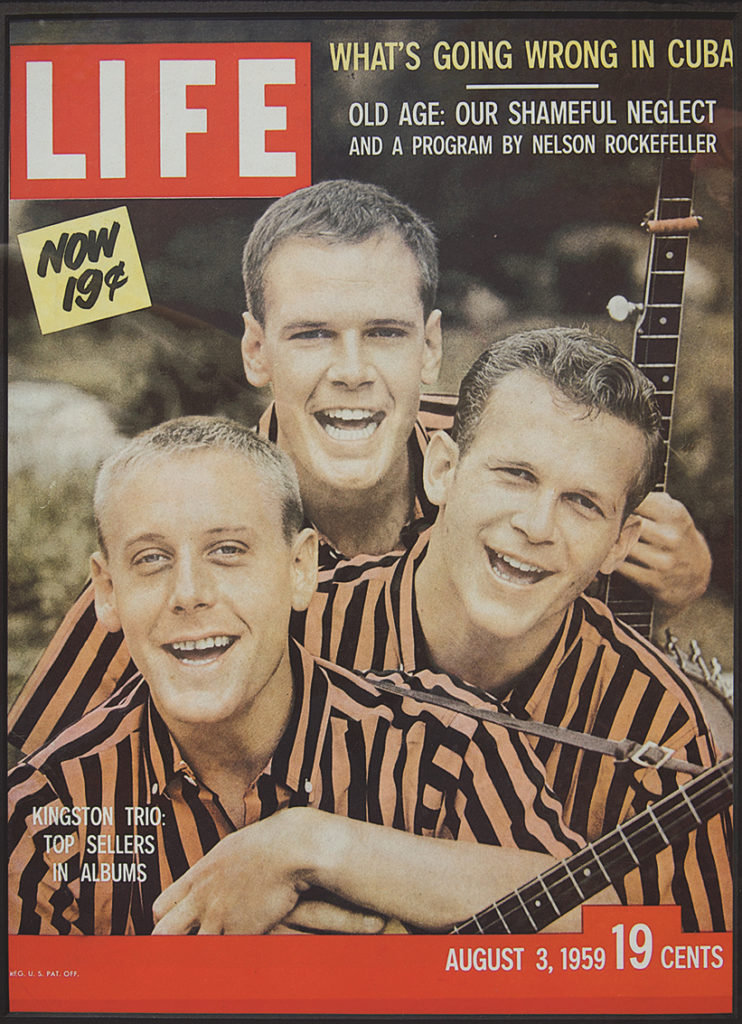

From their inception, the Kingston Trio dressed in matching striped shirts that they bought at a small shop in Sausalito, California. “I think we also got some at Brooks Brothers,” Shane says. “We wanted to project a certain image. We were collegiate and those striped shirts were the only styles that would fit all three of us. They became so well known that we later had our own line of Kingston Trio brand shirts.” The short-sleeved, striped shirts caused a minor fashion stir in California, and even inspired the Beach Boys to emulate the look. (Truth be told, the Beach Boys did more than just ape the Kingston Trio’s garb; in 1965, at Al Jardine’s insistence, they covered “Sloop John B” from the Trio’s first LP.)

The genre problem would bedevil the Kingston Trio throughout their careers. They were always trying to expand their repertoire beyond the folk songs, but the world at large didn’t seem to care. Over time it began to seem like the Kingston Trio would introduce songs only to have them later become hits for other artists. In 1961, they recorded “It Was a Very Good Year,” a song composed for Bob Shane by Ervin Drake, only to have it become a massive hit for Frank Sinatra. They recorded Will Holt’s “Lemon Tree,” but it was Peter, Paul and Mary and later, Trini Lopez, who had the hits with it. The Trio recorded the first version of “Seasons in the Sun” in 1963, but Terry Jacks had the hit version in 1974.

After a few months onstage at the Purple Onion, the Trio was still a little rough around the edges, but they had forged a winning performance formula. “The nonmusical stuff, some of it was rehearsed, but a lot of it was off-the-cuff, or started off the cuff and then became part of the act,” Shane says. “It was pretty much of a natural thing. We were all pretty natural performers. We didn’t read music and we just would play and sing with tenor guitar, banjo and guitar and just use simple chords, and had good humor and good singing.” The three bandmates developed something of a formula for their stage show, although Werber had to keep reminding Shane to attend to business. “Quit partying after hours: stop being a corny ham; don’t be a clown,” read one of Werber’s many notes to Shane from the early days.

After their run at the Purple Onion ended in December 1957, the group prepared to record their first LP. On February 5, 1958, they headed into the studio in the Capitol Tower in Hollywood, where over the next three days they recorded their self-titled debut record. Capitol producer Voyle Gilmore had previously worked with Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra and Judy Garland. Rather than soak the Trio in strings and grand orchestrations, as was the style at the time, he opted to record Shane, Reynolds and Guard essentially live in the studio.

The stark, guitar- and banjo-driven sound was very unusual to hear on a major label. But in some ways, Capitol was good fit for the Trio. “We would go see folk acts in San Francisco when they were playing,” Shane says. “But that was as much to check out the competition as anything else. If we had the time, we really liked to go to Reno or Vegas and see the lounge acts. I can’t say it enough. We never called ourselves folk singers; somebody else did that. But when somebody calls you a folk singer and says, ‘Here’s a lot of money’ …you say, ‘Oh, sure, I’ll be anything you want.’ Don’t forget, we were all business majors. We loved to sing, we loved to perform, but we also loved to make money. The great thing about the Kingston Trio was that we could do all three things.”

At first, the group’s debut LP had only modest sales, but the Kingston Trio didn’t really notice—because by the time the LP came out the band was in the early stages of what would become an insane touring schedule. They would be on the road playing more the 250 shows a year for the next few years. Initially, they were booked into nightclubs like Chicago’s Mr. Kelly’s and New York’s Blue Angel and the Village Vanguard, venues where they shared stages with jazz artists and cabaret performers. That June, they found themselves playing at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu when they got some surprising news. Two deejays, Bill Terry and Paul Colburn at the Salt Lake City radio station KLUB, fell in love with “Tom Dooley” and started playing the album track. Other deejays across the country followed their lead, forcing Capitol to release the song as a single. “Tom Dooley” made its way up the charts, and on November 22 the record was at the top, an amazing feat for an obscure ballad about a grisly murder.

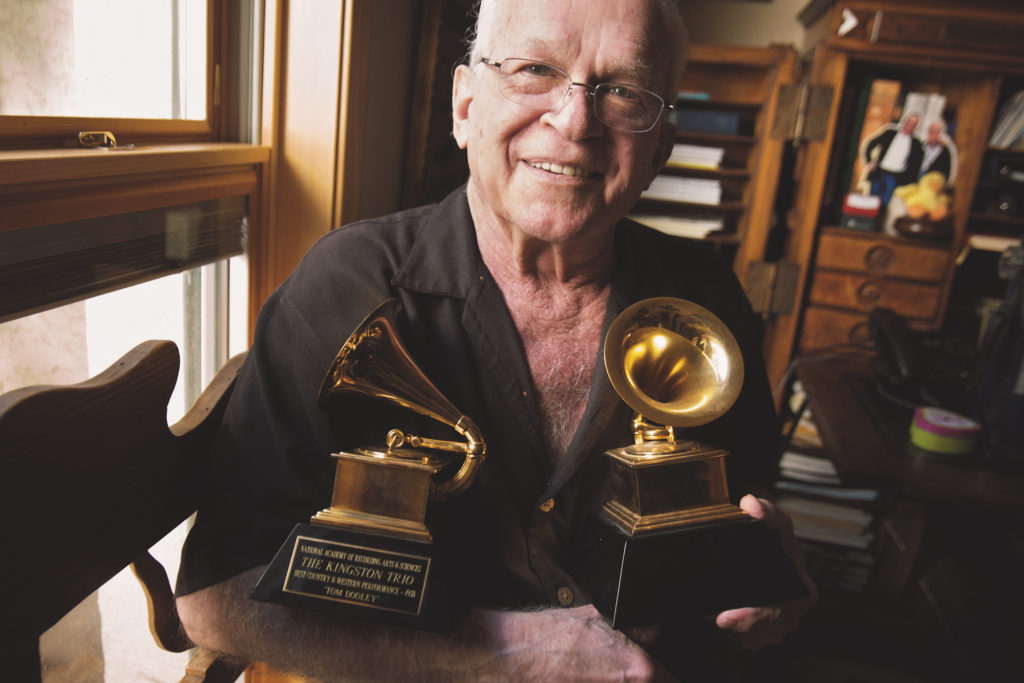

The Kingston Trio ended 1958 as one of the most popular bands in America. In 1959, they continued to thrive—but things began to get a little weird. On May 4, at the inaugural Grammy Awards ceremony, they won the award for Best Country and Western Performance for “Tom Dooley,” a fact that didn’t, and still doesn’t, sit well with the Nashville establishment. “The Grammy people wanted to call us folk singers, to give us a Grammy for folk music, but they didn’t have a folk singing category,” Shane recalls. “So they took liberties and they gave the Kingston Trio the first Grammy ever given for Country and Western.”

That year they released four LPs—…live from the Hungry i, Stereo Concert (one of the first live albums recorded in stereo), At Large and Here We Go Again!—all of which sold very well, with the last two both hitting the top of the LP charts. By now, the Kingston Trio were a national phenomenon and folk songs were a national craze, particularly among younger people. The Trio hit on the idea of playing on college campuses, the first band to discover this lucrative market. “In our first two years of touring, we played 275 colleges,” Shane recalls. “Hell, I didn’t know there were that many! The great thing was that as soon as the show was over, we would walk out into the crowd and sign autographs. Nobody ever did that. And people would ask, ‘Why would you do that?’ And I said, ‘How else are you going to meet the chicks?’”

The Trio was traveling so much they decided it would be more efficient to rent their own airplane to get them to gigs. “We got a 1939 Beechcraft D-18, with a split tail that sat on the ground,” Shane says. “I remember the model number because it was the same as the Martin guitar. We flew in that thing all the hell over. Landed in everything, from gravel fields to grass fields to airfields to whatever. We had our guitars and Dave’s banjo on the plane. Our bass player at the time was David Wheat, but we called him Buckwheat. We hung his bass from the center of the aisle, so there were two guys at each side who could not even see each other because the bass was hanging there.”

Shane says that most of the shows from that period blend together in his memory, but one in particular stands out. On March 15, 1959, their plane developed trouble on the way to a gig at Notre Dame and started to go down. “Buddy Holly had died in plane crash only a couple of weeks before, so the last 15 to 20 minutes we were on that plane, we knew we were dead,” Shane remembers. “So we drank a fifth of booze between the four of us. Our pilot flew B-17s during World War II and he managed to land relatively safely in a field. We stepped off the plane into the snow and some guys were running across the field saying, ‘Are you all right?’ And I said, ‘Parlez-vous Italiano?’ The guy said, ‘No, you are in Indiana.’”

They were only a few miles from Notre Dame and managed to make it in time for that night’s show. “We were backstage and a priest came up to us and said, ‘I understand that you do blue shows,’” Shane says. “I had never heard the word before, and so I asked him, ‘What do you mean “blues,” sir?’ ‘Well, you say “damn” and things like that.’ And we said ‘Oh.’ He said, ‘If you do that, we will just turn the lights and the sound off.’ So, we’re performing in a field house with a corrugated steel roof, with 4,000 people in bleachers. We finished the first opening act and nobody is cheering; David said ‘Father such and such said that if we did any blue material here they would turn off the lights and the sound.’ Then there is this silence. And then a sole voice from the top of a bleacher called out ‘Horseshit!’ And the whole place went crazy. The crowd was pounding their feet on the bleachers and making this weird rumbling sound. That was some day. I remember it just like it was yesterday.”

A few months later they were invited to perform at the first Newport Folk Festival. They were scheduled to close the event, but an outcry from some of the other performers, who felt that Kingston Trio were just capitalizing on folk music, caused George Wein, the festival’s organizer, to have them go on next to last and have Earl Scruggs close the show. But the audience kept calling for the Trio and after Scruggs finished, Wein sent the group back out for an encore.

From the recording made at the festival, it’s clear that audience loved the Trio’s performances, but backstage, a lot of the musicians were incensed. Many perceived the Trio’s encore as an insult to Scruggs. “I lost a lot of friends in the folk world for that slip-up,” Wein later said. Shirley Collins, the English folk singer, succinctly summed up the opinion of most of the traditionalists toward the Trio: “I despised them.” But she did add, “The audience loved them!”

The rest of 1959 was a blur of recording sessions, television appearances and concerts. The hits kept on coming: “M.T.A.,” “A Worried Man” and “The Tijuana Jail” all made the Top 40. “Tom Dooley” sold more than 3 million units.

As 1960 dawned, the Kingston Trio were the most popular vocal group in America, but there were tensions forming in the band. Dave Guard, perhaps stung by the criticism the group received at Newport, wanted to move the band in a more traditional folk direction. He kept insisting that all three members take time out to study the older styles, to try to make their performances more authentic. “Nick and I said, “Gee, Dave, it seemed to go pretty well so far,” Shane recalls. “We’re the biggest-selling group in the world.”

As the year progressed, the group continued to go from success to success. At the 1960 Grammys, they got the award in the new category Best Folk Performance for their LP The Kingston Trio at Large. (No more country music awards for them!)They also continued to release LPs at an almost alarming rate. That year saw the No. 1 Sold Out and String Along, and the Christmas LP, The Last Month of the Year. They played even more concerts and appeared on even more television shows. But as the year came to an end, the tensions in the band continued to worsen. At one point, their accountant made a bookkeeping error. Guard was upset because Shane and Reynolds seemed to be unconcerned about it. It was soon corrected, but that, in combination with the different idea about the band’s musical direction, led Guard to leave the group in May 1961. “We were smart enough to say when we formed the band that if there ever gets to the point where somebody’s really pissed-off with the whole thing, he has the freedom to go anywhere he wants,” Shane says. “Time magazine quoted Dave as saying, ‘Nick and Bob wouldn’t rehearse or learn to read music better,’ or do this, or do that. As I said, we were so busy that Nick and I didn’t see reason to change.”

Guard continued to perform with Shane and Reynolds until they could find a replacement for him. They auditioned dozens of musicians, including a young musician named Jim McGuinn who later changed his first name to Roger and formed the Byrds, before settling on a talented songwriter named John Stewart, which is a story that will be told some other time. Sometime in August 1961, Dave Guard left the band for good. Sadly, the parting was less than amicable. Over the years, the former friends rarely spoke to each other. The new version of the Kingston Trio continued to prosper, until in 1967 the three members decided to call it a day and the band broke up.

The original Trio of Bob Shane, Nick Reynolds and Dave Guard reunited for a PBS television specialrecorded in 1981. After that show aired, Shane and Guard reconciled enough to begin talking about a reunion, but Guard tragically contracted lymphoma and died before the plans could come to fruition.

In the early 1970s, Shane formed a group called the New Kingston Trio to perform different material. He quickly discovered that people really wanted to hear all the old songs. In 1976, he bowed to the inevitable and dropped the “New” from the band’s name and hit the road with various hired musicians to play “Tom Dooley,” “M.T.A.,” “Scotch and Soda” and all the rest until his heart attack forced him to retire. (He currently oversees a version of the Kingston Trio made up of musicians who played in the band in the past.)

Shane is generally happy with the way his career turned out and he’s fiercely proud of everything that he and his bandmates accomplished over the years. For four years, from 1958 to 1961, they were one of the most popular bands in America. They sold millions of records and played thousands of concerts all over the world. They demonstrated the commercial viability of acoustic guitar-driven music, and the folk boom they inspired paved the way for musicians like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez among countless others. They also helped create a demand for acoustic guitars that continues to this day.

But the Kingston Trio did more than just inspire other musicians: they made some damn fine music of their own. And happily, more than 50 years after the group first got together, it looks like the “Are they folk singers?” silliness has finally died down. If it does reignite, perhaps we would all do well to remember these words from Big Bill Broonzy: “All music is folk music; I ain’t never heard no horse sing a song.”

The Tale of the Saga of Tom Dooley

“Tom Dooley” was a real person, but his story was even more sordid than it appeared in the Kingston Trio’s famous song. Thomas Dula, as his name was originally spelled, was born in Wilkes County, North Carolina in 1844. (In the local dialect, Dula was pronounced Dooley, similar to the way opera became opry.) According to John Foster West’s Lift Up Your Head Tom Dooley, an excellent book about Tom Dula’s life and death that’s based on the transcripts from Dula’s two trials, Tom Dula was a randy teenager who was always getting into trouble with the local girls, particularly one named Ann Foster. In 1861 Tom went off to fight in the Civil War. When he returned home, he restarted his affair with Ann Foster, who had married a farmer named James Melton.

Apparently Ann wasn’t enough for Tom, because he started sleeping with Ann’s cousin, Laura Foster, and yet another cousin named Pauline Foster. Tragically, Pauline had syphilis, which she passed on to Tom, who in turn gave it to Laura and Ann. At the time, though, Tom and Ann thought they caught it from Laura. It appears that Tom and Ann hatched a plan to get revenge on Laura. Tom suggested the he and Laura elope, and on May 25, 1866, Laura packed her clothes in a bundle and went off to meet Tom in the forest. She was never seen alive again.

Most of the people in the area assumed that Laura had run away, but about a month later rumors started to spread that Tom had murdered her. In late June, Tom panicked and ran for the border. He wound up working in Tennessee on a farm owned by Col. James Grayson. When Tom heard that deputies from Wilkes County were coming to arrest him, he ran away, only to be hunted down and arrested by Grayson.

Tom Dula was sent back to North Carolina, where he and Ann Foster Melton were charged with the murder of Laura Foster. While he awaited trial, Laura Foster’s body was discovered in a shallow grave, which caused a sensation and inspired local poet Thomas Land to compose “The Murder of Laura Foster,” a long ballad, to mark the occasion. That was the first of three songs written about the murder.

On October 1, 1866, the trial of Tom Dula began. Ann Foster Melton was tried separately. After hearing from numerous witnesses, Tom was found guilty. Tom appealed the verdict and a new trial was held, which also reached a guilty verdict. While in jail, Tom said that he was the sole murderer of Laura Foster, a confession that led to the acquittal of Ann Foster Melton in her trial. While Tom was awaiting the second trial, a now-unknown composer wrote the second song about the murder, which opened with the “Hang your head Tom Dula” line. This is the lyric that evolved into the hit song of the Kingston Trio. Tom Dula himself supposedly composed the third ballad, although today most folklorists doubt that claim. After the second trial, Tom Dula was hanged on May 1, 1868.

After Tom’s death, the three songs remained popular in North Carolina, but over time, the “Hang your head Tom Dula” version won out. In 1929, a duo known as Grayson and Whitter made the first recorded version of the song. (Grayson was the great-nephew of Col. James Grayson, the man who arrested Tom Dula in the first place.) In 1940, a folklorist named Frank Warner made a field recording of Wilkes County native Frank Proffitt singing a version of the song that had the same melody but somewhat different lyrics as the Grayson and Whitter version. (Proffitt’s grandmother had known both Laura Foster and Tom Dula.) Warner himself then created a shorter version of the song based on Proffitt’s that was included in the anthology Folk Song U.S.A., compiled by John and Alan Lomax in 1947. Warner recorded his version in 1952; it was later covered by the Folksay Trio and the Tarriers.

The Kingston Trio’s “Tom Dooley” is very similar to Warner’s version, but they took it at a much slower tempo and added a spoken intro that states the song is about the “Eternal Triangle” and the story of Tom Dooley, Mr. Grayson and an unnamed beautiful woman. (As the history shows, the story was really about Tom Dooley and three women, making the situation more of an Eternal Trapezoid…and Mr. Grayson was just an important but minor character.)

In the early 1960s, Frank Warner and Alan Lomax sued the Kingston Trio for copyright infringement. In 1962, the Kingston Trio reached an out-of-court settlement, and to this day “Tom Dooley,” a song that dates back to the 1860s and was first recorded by Grayson and Whitter in 1929, 18 years before Folk Song U.S.A. was printed, bears the copyright notice “Frank Warner-John A. Lomax-Alan Lomax.” —MJS