The Fretboard Journal is proud to premiere Jack Schneider’s Best Be On My Way album, officially out on November 11, 2022.

For the last few years, we’ve been hearing all about Jack Schneider. He’s a young and uber-talented Nashville-based singer-songwriter who seems to check all of our favorite boxes: Jack has immersed himself in vintage instruments working alongside George Gruhn at Gruhn Guitars; he’s toured with Vince Gill as both a guitar tech and rhythm player; and he’s collaborated with David Rawlings, among many others.

On Best Be On My Way, he incorporates all of the above with some stellar guests (yes, Rawlings and Gill are on there); some incredible vintage guitars; and truly great songs. This doesn’t feel like a debut at all. Check it out via the above Soundcloud link, give it a listen, and share this page with friends.

Jack on His Guitars with Vince Gill

“My main two acoustic guitars for working with Vince are a custom herringbone Martin 0000-28 I bought from George Gruhn in Nashville. I had some of the finish sanded off from the body, which helped the guitar open up quicker.

“The other instrument is a guitar made by the late, great Carlo Greco, former foreman of Guild Guitars in the 1970s. He built this one in late 1999 for a neighbor. I discovered who Carlo was by researching several iconic guitars I coveted as a child: Paul Simon’s main 1960s Guild F-30R, John Denver’s Guild F-50R Special and F-612, and the acoustic parlor guitar that Mark Knopfler played on Bob Dylan’s Infidels record. All instruments I discovered had been built by Carlo himself at the Guild factory, and I found Carlo’s name in the white pages and called him up. I was seventeen, he was 88. He could not have been kinder and answered many of my questions about guitars and instrument construction. He passed a few months later, and I sought out one of his guitars for a year but never found one. Then, right before my high school graduation, this one showed up online. I spent all my college money on it, and my folks helped cover the difference. They surprised me with it on the day of my high school graduation.

“This old friend has traveled the world with me. From my first days of college in New York to beer joints in a punk band to the streets of Paris to the Ryman stage with Vince, it has been a joy to grow with this beautiful instrument… and to accumulate miles together.

“Both instruments are equipped with Paul McGill Go Acoustic Audio pickups. I run them through a Grace Felix pre-amp, and have a Strymon Flint on my pedal board for reverb which I will use from time to time, depending on the room. Tuner pedal is Boss Tu-3.”

On Best Be On My Way, Jack’s primary writing guitar was a 1956 Martin D-28 dubbed “Big Jim” (pictured in the gallery below). It was formerly owned by Gillian Welch. “I bought it from her and David in January 2021, wrote many of the songs on the record on it, and played it on almost every song,” he says.

He also used a 1964 Gibson B-45-12 12-string on “Marietta” and “Del Rio Blues,” and wrote many of these tunes on a 1970 Martin D-41.

There’s also a custom sinker Mahogany Martin 0000 12-fret twelve-string guitar on “I Still Believe In You,” which was tuned to open Eb. And on “Don’t Let Our Love Start Slippin’ Away,” Jack borrowed one of Vince’s custom 0000 Martins and strung it with a 5-string open G tuning, a la Keith Richards.

Meanwhile, Vince performed on “Farewell Carolina” and “Nothing Left to Show” with this 1930 Martin OM-45. Jack says, “It’s truly one of the finest guitars I’ve ever heard.” (He liked it so much, he played it himself on “In the Morning.”)

Jack continues with his gear rundown: “I use Kyser capos exclusively. They were kind enough to make me custom low-tension capos for the summer tour and I am crazy about them. Normal Kyser capos are great for harder playing, but the tension can make the guitar go out of tune as you capo higher up the neck. I play so lightly that I don’t need the extra tension, and these custom capos don’t make the guitar go out of tune between different capo positions.

“For picks, I use D’Andrea mediums, rounded edge. For lead, I’ll switch to a Dunlop Tortex .73mm, or a D’Andrea Extra heavy. D’Andrea has the best-sounding celluloid, in my opinion. It is closest to the sound of my favorite vintage Fender picks from the 1950s and 1960s.

“For strings, I’ve been cycling through a few different favorite sets. I really like Martin Darco 80/20 light gauge strings. They have a slightly heavier G string and a slightly lighter A string, which is good for my particular touch. I do like D’addario EJ16s and use those pretty consistently. Sometimes I’ll use Ernie Ball Earthwood Medium light 80/20. The 80/20 strings I think sound better straight out of the package but die faster. I’ll pick strings depending on how many shows in a row we are going to be playing, and what the venue conditions are. High humidity kills strings a lot faster.”

Best Be On My Way: Track Notes by Jack Schneider

1. “Josephine”

“Josephine,” composed with my friend and collaborator Wes Langlois, was recorded live to analog tape at Sound Emporium Studio B in Nashville on July 2nd, 2021. Featuring David Rawlings on lead acoustic guitar, Stuart Duncan on mandolin, Dennis Crouch on upright bass and Liv Greene on harmony vocals, Josephine came to life organically, in a matter of just two or three takes. The song itself showed up a few weeks before. Wes had written the chorus already, a melodic ode to a character from the distant past, a memory preserved in the framework of the cadence. The verses were written around that image to capture the essence of a fleeting memory, one that lingers, evolving with the passage of time. The recording itself fell into place quite similarly. We all played to that figurative image, and the result encapsulated the sense of movement outlined in the lyrical narrative.

2. “Farewell Carolina”

Wes Langlois and I wrote “Farewell Carolina” the week before the initial recording session. The melody came first, and the story formed around it. As we wrote, the figure of Carolina emerged: a symbol for the unstoppable motion of life, of inevitable new beginnings and difficult goodbyes. Vince heard this song in its infancy and suggested a few revisions, and when we got to the studio, it was he that suggested the song be one to try putting to tape. He pulled out his guitar — a 1930 Martin OM45 — and laid out the foundation. By the end of the first take, it was clear that my role was to tell the story, not to perform it, so I set down my guitar. Between Vince, David Rawlings, Stuart Duncan, and Dennis Crouch, the image of Carolina — place, person, and memory — was brought to life.

3. “Marietta”

When Wes and I sat down to write on June 14, 2020, we started with a song originally called “Henrietta.” We loved the melody and lyrics we’d come up with, but it didn’t feel right to have a character conceptually waiting “just around the bend.” Instead, I suggested changing the title to “Marietta,” a city just outside my hometown of Atlanta, Georgia. In researching Marietta’s historical significance, we stumbled upon the fact that on the very day we were writing the song — June 14 — in 1864, a confederate general, Leonidas Polk, was shot in half by a Union cannonball at the Battle of Marietta. Upon this discovery, the song became something of an anti-war piece, a cautionary tale against a “game that you can’t win.” Ultimately, it is a meditation on the impending demise we are all walking towards.

4. “Tennessee”

“Tennessee” was the first song that we recorded for the album, and thus it served as a discovery of form, setting up a framework for the remainder of the record. Our approach to that first recording was hands-off and natural: We only needed one or two takes to capture the essence of the song, and for the most part, that ease and spontaneity were a consistent tenant of our workflow for the entirety of the project. The song itself was largely composed by Wes as an exercise in trusting in cadence, and it feels important in the context of the record as both a concrete narrative and a point of universality for the listener. Like many of the pieces on the record, it’s a journey song, an Odyssey-like story of going off on an adventure and returning to see if the one you love is still there. It’s about coming to peace with the undoable and trying to salvage what you can after all is said and done, and its figurative intersection of the geographical and the personal is imperative to the record as a whole.

5. “Best Be On My Way”

At the heart of the record is its title track, “Best Be On My Way.” It’s a song that encapsulates a life philosophy of surrendering to forward motion, an honest admittance of both our ignorance and our responsibility in existence. It’s a march toward death, in the most uplifting sense. This piece was a true collaboration between Wes and me: We wrote the chorus together, Wes banging on his Martin in the kitchen while making coffee, and then we each wrote five or so verses and stitched the story together out of the best of them. It’s the only song on the record in which I play lead guitar, and its placement at the end of side A was strategic in its use of symbolic momentum to push the record toward side B. Ultimately, this song epitomizes not only the narrative moral of the project but also my own attitude toward life: that despite the unknowns of existence, one’s only option is to keep going.

6. “Don’t Look Down”

“Don’t Look Down” was written on a stormy night in Nashville sometime in the summer of 2021. It showed up fortuitously, a simple piece reflecting on the nature of the previous year: the turbulence, the chaos, the world feeling like it was tearing at the seams. The song emerged as a glimmer of hope, a reminder of the ground beneath my feet, the simultaneous wariness of—and trust in—forward motion. When I began recording the album, “Don’t Look Down” was tucked away in the back of my mind, abandoned but not forgotten. Following the first full day of tracking with a band of heroes—Vince Gill, David Rawlings, Stuart Duncan, and Dennis Crouch—I found myself back in Sound Emporium’s Studio B to shoot some photographs and video content for the half-formed record’s eventual release. On a whim, I had recording engineer Mike Stankiewicz set up the tape machine and one mic, a vintage Neumann U67. I pulled out a guitar and set foot in front of the mic, and that ephemeral tune came to me once again. Liv Greene, an old and dear companion I met at Interlochen summer camp as a teenager, was there for video filming, and I invited her to join in on the banjo.

We played the song once for the camera. It was an imperfect take: I got some of the words wrong, my voice was still learning the cadence, my fingers still finding their way around the melody. But the essence of the song was intact. The journey was in motion, and the feeling was overwhelming. Months later, when mixing the record, I was narrowing down songs with David Rawlings. “Don’t Look Down” was on the cutting room floor up until that point, but Rawlings came to its rescue. At his advice, I included it on the record, and it has since come to function as a pivotal point of reflection both in live shows and in the musical narrative of the record itself.

7. “Slow Things Down”

Wes and I wrote “Slow Things Down” on a trip to play a private event in Gasparilla, Florida, and it fell together seamlessly both in its composition and recording. We were killing time by the pool late one night, looking out over the ocean for the first time since before the pandemic, and this song showed up simultaneously with a great wave of calm, an exhale of freedom, a feeling of the body sinking into itself. It’s impossible to go on a journey without sitting back to observe the miles traveled and the miles left to go, and that’s exactly what this piece is doing. The manner in which we recorded it was completely loose and unrestrained: the additional solo at the end — where David Rawlings and Stuart Duncan shine on guitar and mandolin, respectively — was completely unplanned. It was proof of concept that when you surrender and step back, the work will do itself, and both transparency and freedom will emerge.

8. “Nothing Left To Show”

“Nothing Left to Show” was an exercise in the intersection of Nashville and Texas-style writing, a song about being down and out that lives somewhere in the world of Townes Van Zandt and Rodney Crowell. While lyrically and sonically a deviation from the rest of the record, it’s equally vivid in its narrative, which takes place in Houston and is loosely based on the film Paris, Texas. The magic of this particular song materialized in the recording process when Dennis Crouch breathed new life into it with his part on upright bass. The bass line is moving and pulsing, accentuating and extending the space between notes rather than framing the song’s sections. It gives new meaning to the song’s sense of boredom, of seconds ticking by. This is the second song on the record on which Vince Gill lent his velvety harmonies, in addition to the main part on his 1930 Martin OM-45.

9. “In The Morning”

Irish folk music has had a huge influence on my songwriting and artistry, and Wes and I wrote “In the Morning” during a time when I was listening to a lot of Mícheál Ó Domhnaill, Paul Brady, and the Bothy Band. It came out of a study on the impressionistic nature of that tradition and was our attempt to encapsulate the feeling of deep and unresolved tragedy those artists have tapped into. The recording itself, which is rather soft and pretty, stands in contrast to the dismal nature of the story: that of a man whose love has died, and whose only motive to continue living is his nightly dream of seeing her again when he awakes. Tracking this song with Stuart Duncan on fiddle felt like having a conversation with a ghost — my vocal followed Stuart’s musical intuition, narrating the tale in dialogue with a symbol of the perished lover. I played this song on Vince’s OM-45, tuning it to open D and playing the part as closely as I could to what I imagine Mícheál Ó Domhnaill might have played: a meditation on beauty and darkness, and how they inform one another.

10. “Del Rio Blues”

In many ways, the record ends with “In the Morning,” and “Del Rio Blues” serves as the soundtrack to the credits rolling, the music lingering on as you’re walking out of the theater. It’s an obvious sonic departure, an epilogue, a tip of the hat to the intersection of Neil Young’s Harvest and Bob Dylan’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (a representation of the duality of self that Wes and I refer to as “Dylan Young”). The recording is overcooked, but we ended up liking it: the inclusion of electric guitar (David Rawlings) and drums (Griffin Photoglou) reframes everything that comes before it, and forces the listener to reconsider the miles they’ve traveled thus far. The record ends in a fade-out, an allusion to its boundlessness: panoramic yet humanistic, a denial of a finite horizon.

On behalf of all of us here at the FJ, we hope you enjoy this early listen to the album, and huge thanks to Jack for walking us through it.

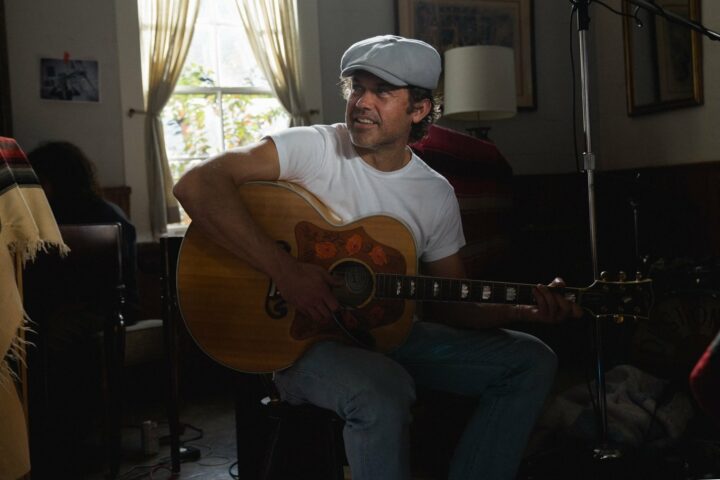

Above photo: Nathan Rocky