You know what? Your favorite amplifier might owe a bit more to a drummer than you might have thought possible. Bryan Sours, of Portland-based Soursound, has pounded the skins in bands much louder and heavier than anything you’ve heard, probably, and he makes the output transformers favored by hotshot amp manufacturers like Benson and Otis. He also builds his own amplifiers (either custom or in small batches), one of the slickest one-knob boosts on the market, repairs amps and has recently delved into the arcane world of tape echo service and repair. His plate, to mangle a phrase, runneth over, so he’s a natural fit for our Bench Press column, but it was too much to manage via our usual email interrogation, so we got him on the phone, talked forever about everything, then whittled things down to a manageable conversation focused on those magical output transformers…

Fretboard Journal: So how did being a drummer in bands lead to what you’re doing now?

Bryan Sours: I was always kind of the guy in the band who would be sitting there playing drums and saying, “I’ll turn the mid up on that thing. I can’t hear you. You need to kind of like punch through or turn the gain up…” I was always the backseat guitar player. That’s probably a good term for it. I was always the annoying guy telling, telling everyone else how to sound.

I grew up working on computers with my dad. So I was always kind of into just gear in general, and I love the idea of recording. So I started that. I started working in studios when I was pretty young too. And, from studios, I wanted to be an engineer for a living and I was for a little while, and it’s kind of a weird world to exist in, I mean, at least like back back then…

FJ: When was this?

Bryan: Oh, back in like the late nineties. And there was always the financial entry point to stuff like that. So, I ended up going to school for engineering, and at one point in — when was that? I think that was like 2001 — I had a class that was just studio maintenance. It was one of those classes where lthey teach you Ohms law and what components are; no one really cared about the class, but it was actually a really good class and we’d have these labs and you build, like, little oscillators and stuff and I’d get my work done. And then I’d take the parts that were there and, while I was reading about distortion pedals online, then I’d try and make a distortion pedal and fail miserably.

But I had an instructor that was like, “Hey, you’re, you’re interested in this stuff. Would you ever want to work on gear?” There was this repair shop that he worked at that wanted to hire kind of a younger apprentice type that didn’t really know anything… And then they say, “Oh, you don’t know how to solder anything. Let’s start from scratch.” And that kind of got me into like repair means mentality. It’s like trial by fire. You’d get handed a piece of gear and the work order would say, this is what it doesn’t do, or this is, this is what it does that it shouldn’t do… something like that. And I’d have about 10 to 20 minutes to recreate the problem and figure out at least the section that it’s in or potentially just figure out what the fix is. And if I didn’t, well, it got yanked off the bench and the owner of the shop would take care of it and they put something else in front of me.

And at first you’re just passing gear, you’re not really figuring anything out and then [the boss] would work on it later and say, “Hey, here’s what was wrong with it? Does this make any sense to you?” And of course at first it’s like, no, I don’t really get it. But I caught on really fast and I started actually figuring out what was wrong with stuff.

And then eventually I moved to Portland and started doing pedal and solid state repair, ‘cause there was no one doing that and I couldn’t really get a job anywhere. So I started doing that at home and everything kind of went from there. And then I, I ended up working at a shop [Old Town Music] doing pedals and keyboards and stuff. And there was another guy [Jeff Brown] who ended up leaving to start his own shop and we stayed friends and shot work back at each other. I started doing the tube amp stuff there. This was probably like, well, it’s kind of blurry… 2004, 5? That sounds, that sounds about right. Maybe 2006 when I took it over.

FJ: You’re in a strange little niche where you’re building components and devices and amps and…

Bryan: Yeah, it’s too much stuff. It’s a pretty wide view. Part of that is just ADD. [laughs] And it’s the fact that I have an interest in every detail, every aspect of everything involved with what I’m doing. It’s very hard for me to go, “Well, I just want to do this,” or “I just want to do that” because, quite honestly, being a small business, being an independent business in this industry, you have to do a little bit of hustling, and that’s really not the right word. I should be careful with that word. It’s not the right word, but… we’ve all seen high-end builders that also still do repair work [for] cashflow… managing the business and actually making it so you can pay your bills and all that stuff. So as much as I’ll find this niche and I’ll get in there and chase it down the rabbit hole, there’s still all of this work to add up to the final product, which is paying my bills and having sort of a life. It’s a very difficult thing because I want to wind transformers, I want to work on all these tape echoes, I want to build amps, I want to design pro audio gear, I want to do some pedal stuff. And it’s tricky because the balance between them all is… almost like unobtainium. It’s this constant, “What do you want to do? What pays the bills? Can you make what you want to do, pay the bills…” But you want to do all these things.

I don’t want to say that I’m going to be doing this or that forever. You specialize a little bit more and I feel like the transformer stuff is obviously super-specialized, and so is the tape echo stuff. I’m doing a lot less amp repair these days, that’s for sure. I’m not really taking on new clientele with that stuff. I only have a certain amount of hours per week to do that work. And as far as [amplifier] builds go, I’ve got some older build projects that I’ve committed to, that I need to get wrapped up, that I’m admittedly a little bit behind on, and then I’ve got people asking me about building amps after that, and I’m not exactly sure where that’s going to go. You don’t want to over-commit and I’m already kind of over-committed.

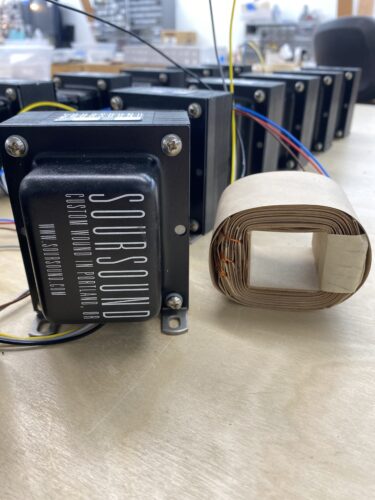

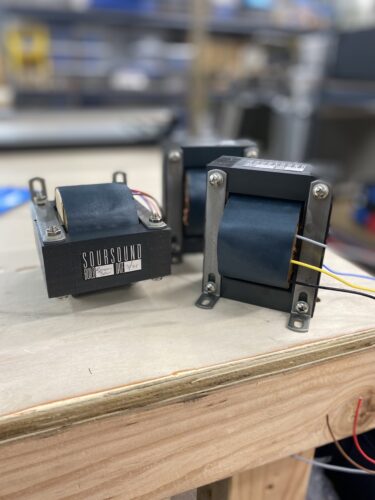

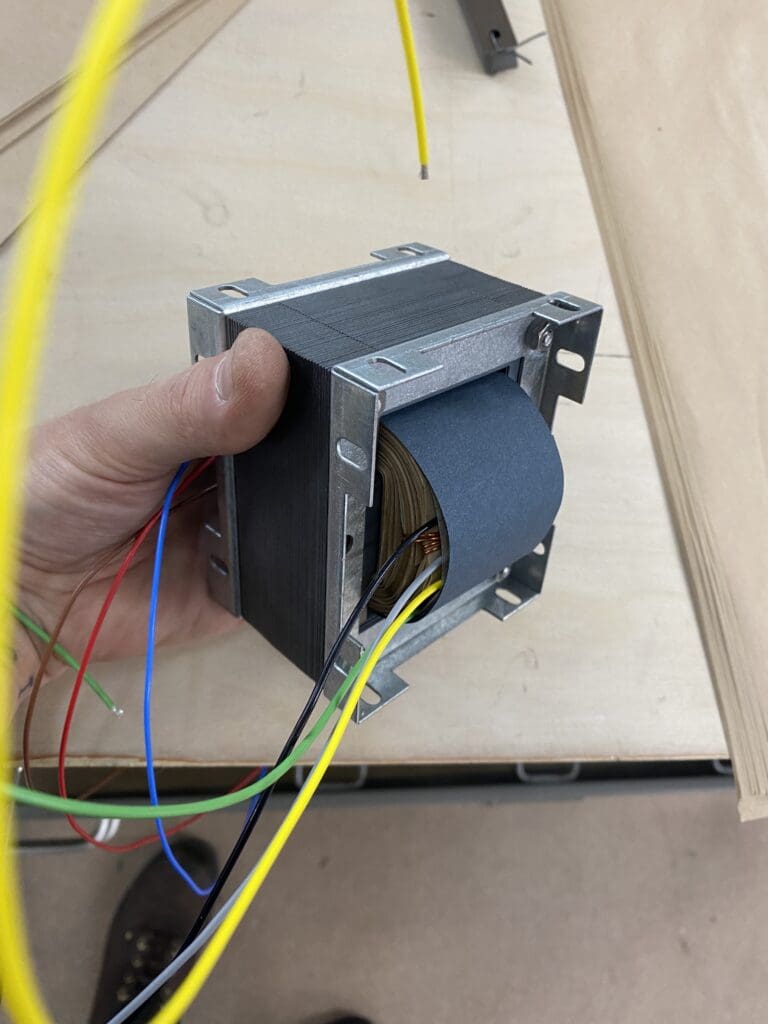

The transformer winding stuff… it’s bizarre. It just keeps growing. I get emails from people all the time. I’m currently pretty deep right now into this winding batch for August over at Otis Amps. I just packed up a big order for Benson and then they dropped another big one on me. So, I mean, I like kind of put together my winding calendar for the next couple of months and, man, I got a lot of stuff to build.

It’s exciting! It’s growing and I feel like I could probably grow it to whatever size I really wanted to. It’s all about what I was saying before: you got to find the focus and then figure out how much focus you can allot to it and then balance it with everything else. I’m sure you’ve talked to builders and people in this industry that have that same issue — they’re interested in a lot of things and they want to do a lot of stuff and they have passion for all these things and [there’s] that ever-elusive sense of balance, of all the different hats you have to wear. You’ve got to manage the business, but you also have to wind a transformer or design transformers and the creativity that’s involved with things like that versus just maintaining a business, it’s… Yeah, it’s the ever elusive balance.

FJ: How did you start winding transformers?

Bryan: Part of it… it’s kind of odd. I mean, part of it was out of necessity. Part of it was out of a desire and passion to chase something down the rabbit hole. In the early days when I’ve worked with other companies, I did pretty loose specifications and as I learned more and was more exerting design control over what I was building… an amp here or an amp there. It became another tool in the voicing process, in the design process.

I think with boutique amps in general, especially small builders, in the end, what you’re buying is not just what’s actually been built, but the vision and the creativity and the passion that went into even designing it and then the ear that’s there for the voice. The same thing with guitars, same thing with electrics, acoustics… it’s not just about the skill of the execution. It’s about what the idea was.

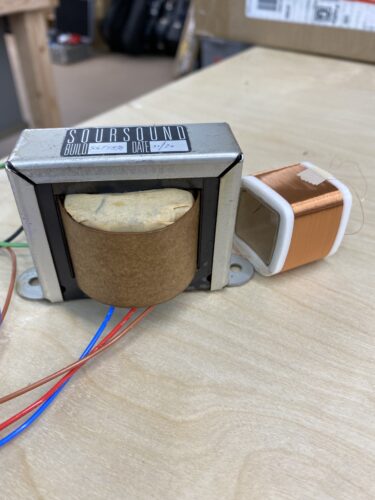

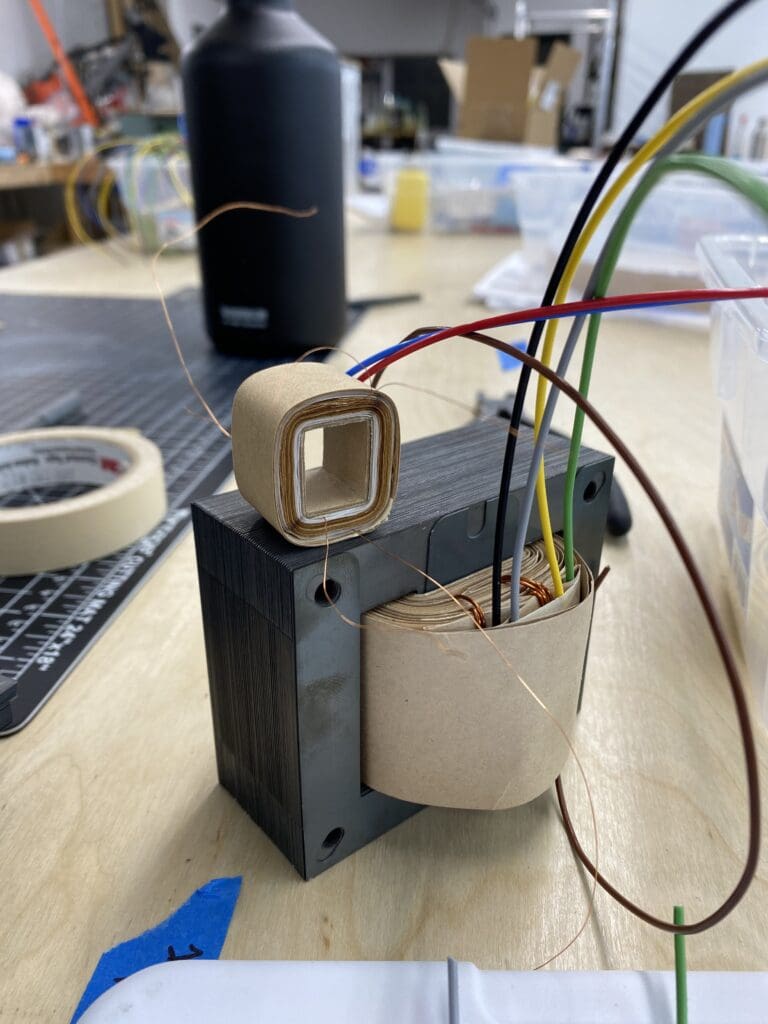

Transformers are something that — specifically output transformers, but power transformers and, and power supply chokes and audio inductors as well — a lot of builders tend to think of as black boxes. To me, it’s just another thing that I can control, another thing I can utilize in achieving this idea, achieving this vision of what I’m designing is. Over the years of building amps, I started spec’ing more and more things: I want this material, I’m looking at this lamination size…

Once I got to the point that I started winding wire? I’m not going to say my first transformers were any good, but I feel like once I was able to do that… I kind of got the bug, for lack of a better word.

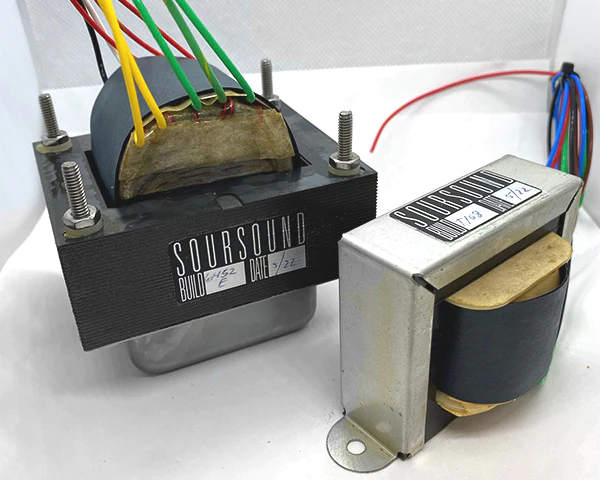

FJ: Do you make output and power transformers?

Bryan: I don’t make power transformers for production. Same thing with inductors, purely because I’m winding everything myself. It’s not like I’ve got winders down on the floor and I just sit up in the office and do design work. So it’s really a time constraint. I’ve done power transformers for my own projects and I feel like the next time that I release an amp design, everything in there is going to be wound by me for sure, but for production, specifically outputs.

FJ: I’m fairly ignorant about the process for winding a transformer. Is it much like winding a pickup? You have a spindle…

Bryan: Yes and no. The basic concept is what it is. It’s turning wire around a permeable material. That’s pretty much what it is. You’re just making an electromagnet. With transformer stuff, I think a lot more goes into design than what would be required with a pickup… there’s a little bit of design and, on paper, go through all your equations and look at what your potential leakage, inductances, what your potential capacitance is, what your primary inductance is, all these, all these things. And then in the end you still have to test it and see what it does. I don’t know a lot of pickup winders, but my assumption is that they have to go through a lot of those same processes.

One of the things I try to bring to the table with making amplifier transformers, at least, is that I have this experience of building and specifically repairing all of these old amps for so long now that,I’m able to design something that is as much a part of the voicing that a builder is doing. That’s kinda my focus… to work with another builder who has a vision, or has an idea, has a voice in their head thatthey want to bring to life. And the idea that this black box, this thing that’s historically been thought of as a black box is actually just another tool for the voicing.

A lot of times I’ll actually put these components into test beds or into prototype units and play them and see what this stuff sounds like. Especially if it’s custom work for people. All the Benson stuff that we did, we started from scratch and he would give me specs and I would design something and do a loose prototype wind of it, just kind of see where we’re at, do some tests, build something a little tighter and then say, okay, let’s listen to this.

FJ: What are the specs for that he gives you? Is it voltage that you’re controlling? Is it current? Again, this stuff is a mystery to me…

Bryan: Without getting too technical about it, basic specifications are going to be how much power is going through this thing, how much power is being developed by the output section that you need to couple to the speaker. And what’s the approximate load that you want the output section to see with this speaker. Do you want an 8 ohm tap? Do you want a 16? Do you want 8 and 16? What are the consequences of having both of those in there? And then just, like, this “nontechnical spec,” is kind of what I call it, where it’s like, what do you want this thing to sound like? What are you after? Tell me a little bit about the amp. And a lot of times I’ll be given some specifications along the lines of a schematic or just a bare bones breakdown as to what the output section’s actually doing, and then, honestly, I treat it like I’m building an amp: what do I want? If this is the goal and we want this, this type of feel, this type of sound, this type of reaction, what is the transformer design gonna need? Is this something that doesn’t have a lot of interleavings, or is it something that’s highly interleaved? Do we want high permeability or medium permeability material in there? Do we want to undersize the core?

I kind of do the technical approach to whatever this abstract sonic goal is for the builder, and in the end, it’s a cool thing because it forces me to kind of say, “Well, I know what I would want, but what does this person want?”

FJ: It sounds like Chris and August and others are not necessarily coming to you for a “Sours” sound; they’re coming because you’re able to give them the Benson sound or the Otis sound…

Bryan: Sure. Or even something that’s like an amalgamation of all of those, or even a sound that they didn’t necessarily quantify ahead of time. That’s how I like to approach it. The goal of me winding for other people is not, “Here’s a spec, make what I want,” or “Here’s an off-the-shelf, just let me get that.” That’s part of a business, but the he drive, the passion behind it is really to take these abstract concepts — What do you want this to sound like? What do you want this to feel like? — and try and put something tangible that either achieves that or achieves something that you didn’t necessarily know was a possibility… not to sound overly artistic about it, but I mean, honestly, that’s my thing behind it. I have trouble looking at it as a business. I look at it more as a kind of a challenge.