Like so many respected musicians–Jimi Hendrix and Charlie Christian among them–Otis Taylor began with the ukulele. Back in the early 1960s, Taylor’s mother gave him a ukulele, and when young Otis broke a string, he took it into the local music store to get it fixed. Fortunately, the local music shop just happened to be the Denver Folklore Center, one of the first stores in America to specialize in fretted instruments. As soon as he walked through the door, Taylor was entranced by the array of new and vintage instruments.

“I went to the Folklore Center and just never came out,” he recalls. “The people were so nice. There were all kinds of instruments hanging on the wall–guitars, mandolins, things I didn’t have names for–but, for some reason, the banjos just sort of called to me. I don’t know why I liked the banjos so much; I just did.”

Almost immediately, Taylor put away his uke and devoted himself to learning the five-string banjo. He didn’t have the money to pay for lessons, but he was obviously so eager to learn that the store’s teachers would give him impromptu playing tips during their breaks.

According to Harry Tuft, founder of the Denver Folklore Center, Taylor was always hanging around the store; thanks to the steady stream of musicians coming through the door, he had a chance to meet some legendary players.

“Back in the 1960s, players heading from one coast to the other would make it a point to stop by the shop,” Tuft remembers. “We ran a small concert hall next door and booked all kinds of players. I remember, once, the Reverend Gary Davis was in town for a week and spent hours in the store playing and answering questions. Doc Watson spent a lot of time trying out guitars there, as well. And Otis was there to hear them all.”

Taylor’s musical education continued at home. He was born in Chicago in 1948, but after his uncle was murdered, his parents moved to Denver in search of a safer area to raise their kids. His father worked for the railroad, while his mother stayed home to take care of the children. Money was scarce, but there was always enough for the occasional jazz, blues or R&B record. Taylor’s father loved jazz, particularly bebop, and his mother was a fan of blues and soul singers like Etta James. Thanks to the tutelage of Folklore Center teachers like Mike Kropp and Mac Ferris, Taylor had learned to frail the banjo in short order and he even picked up a little of the three-finger Scruggs style. Otis Taylor was something of a budding showman and was often spotted around Denver playing the banjo while riding his unicycle, proudly displaying his growing mastery of two esoteric arts.

Along with his lessons in music, Taylor began to learn the history of his chosen instrument, a history that had some painful racial connotations for the young musician. “I had been playing for over a year before I learned the banjo was originally an African instrument,” he says. He learned how the ancestor of the modern banjo had come from Africa with the slaves in the 1700s and how it had become popular as part of the traveling blackface minstrel shows that crisscrossed America after the Civil War.

Taylor’s picking progressed rapidly; sometime around 1964, he met the legendary banjo picker Doug Dillard at a party and played for him. Dillard was very impressed and suggested that Taylor enter some of the banjo contests that were held in the southern part of the U.S. “I was aware of what was happening with the Civil Rights marches and so forth, and for the first time it hit me that the music I was playing, the bluegrass and the old-time music, came from the South,” he says. “So I freaked out and sort of stopped playing banjo so much because I thought I was playing the music of people that hated me.”

Taylor began to devote his energies to learning blues guitar and harmonica, only picking up the banjo from time to time. In 1965, when Taylor was 16, he formed the Butterscotch Fire Department Blues Band. “That was my first group,” he recalls. “We got together and only played one job, the Mr. Colorado Bodybuilding Pageant.” In 1967, Taylor moved from Denver to Boulder, drawn by the burgeoning rock scene. “All the bands in Boulder seemed to be into blues rock, which was easy for me to play,” he said. “Plus, there were lots of girls, and it was just a much hipper scene than Denver.”

He formed the Otis Taylor Blues Band and gigged frequently, but didn’t manage to record. In 1969, he went to England to pursue a record deal with Blue Horizon, the label that released some of the first Fleetwood Mac recordings, but nothing came of it. In 1970, he found himself back in Boulder, where he met Tommy Bolin. The two musicians formed T&O Short Line, which only stayed together for a handful of concerts. “We did get a great poster for the band, though,” Taylor notes.

Taylor and Bolin played together off and on during the next couple of years, until Bolin went on to play in the James Gang and was later tapped to replace Ritchie Blackmore, who was departing from Deep Purple. In 1976, Bolin died of drug-related causes, and although they hadn’t played together in quite a while, that event, coupled with his lack of success in scoring a record deal, caused the disillusioned Taylor to drop out of the music business.

Taylor kept busy during the next few years. He became a successful antiques dealer and an expert in what are now known as “mid-century modern” pieces. He also brokered the occasional vintage car and, in the 1980s, coached an amateur bicycling team. Taylor continued to play music with friends and family but no longer tried to make a living with it. Then, in the mid-1990s, a friend asked him to play for an event he was organizing.

“I told him I’ll call some people to come play,” Taylor says, “so I called my friend Kenny Passarelli to come play, and we had fun. So we did it again and again, and all of a sudden, in 1997, we made a record. So I had no intention of going back into music. My wife used to say there’ll never be a second album; that’s what she used to tell me.”

Thirty years after leaving home to become a working musician–and then quitting the music business altogether–Otis Taylor finally recorded his first album. That record, Blue-Eyed Monster, introduced a relentlessly rhythmic style that Taylor later dubbed “trance blues.” Taylor played electric and acoustic guitars as well as mandolin.

Taylor’s songs are intensely felt, and their primal power can make them sound as if they were channeled rather than composed. “My songs, they come to me like dreams, sometimes,” he says. “I can sit down and write a song on purpose, and sometimes when I play guitar, a song will come to me. But the best ones come to me before I get to the guitar, you know what I mean?”

His lyrics tend to tell tales from the bleaker side of life and deal with murder, racism and injustice–themes that reflect the sometimes-harsh circumstances of his upbringing. But Taylor’s harrowing words are offset by a compelling percussive drive and soulful melodies that suggest redemption is more than just a possibility.

Blue-Eyed Monster sold well enough to inspire a follow-up, When Negroes Walked the Earth, and before he knew it, Taylor was back in the music business full time. He continued to refine his trance-blues style–characterized by chugging, hypnotic rhythms, slowly changing harmonic patterns and passionate lyrics delivered in a powerful growl. He was also adding songs with more-traditional blues forms into the mix, which made his albums sound like the past and the future were happening simultaneously.

Before long, the release of each new Otis Taylor CD was a welcome event in blues circles and among other discerning music devotees. Taylor routinely graced the annual best-of lists and began to rack up an impressive number of awards. He also reached into his past and started to play more banjo on his records.

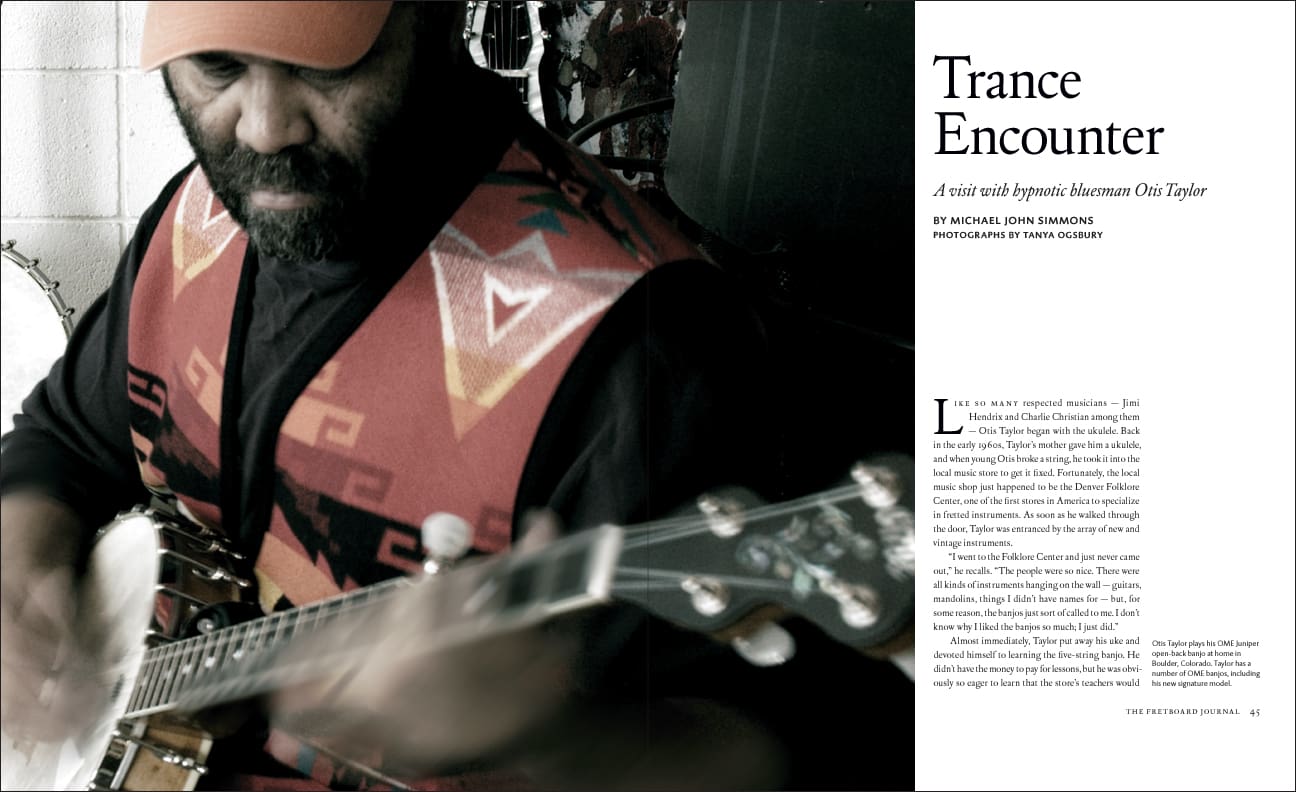

Taylor uses a hybrid technique that includes elements of clawhammer, which is common in old-time string-band music, and three-finger picking, which is favored by bluegrass pickers. He eschews finger picks, opting instead to pluck the banjo with his bare fingers. This gives the instrument a slightly muted tone that sets his playing apart from the bright, almost metallic tone that comes from playing with finger picks.

As the banjo popped up on more and more tracks, Taylor occasionally would run across a writer who suggested that the banjo was not really a blues instrument–that it was really supposed to be for bluegrass.

“Well, that’s their mentality,” Taylor says. “It’s my cultural music, so when they want to tell me what I can or can’t play, I just think, You got to be joking! My music is very rooted in the African tradition, you know, and the banjo’s roots are African, as well.” As aggravating as the comments were, they inspired Taylor to rethink the banjo’s place in his music. He decided to get together with some of his friends and reclaim the banjo’s heritage as an African-American instrument.

The result was Recapturing the Banjo, which includes guest appearances by prominent blues artists Guy Davis, Alvin Youngblood Hart and Keb’ Mo’–all of whom play five-string banjo on the CD. Don Vappie, who plays early jazz with the Creole Jazz Serenaders, represents the four-string banjo.

“All of these guys had something to say on the banjo,” Taylor says. “I wasn’t trying to make a total history of the instrument. I wasn’t trying to re-create some lost moment. I was trying to show that the banjo has a modern voice, not an antique voice. And everybody was basically onboard and liked the idea.”

The bulk of the tracks on Recapturing the Banjo are Taylor originals, with a few well-chosen covers added. (Steve Martin once joked that it was impossible to play a sad song on the banjo; he’d obviously never heard one of Otis Taylor’s compositions.) When Taylor and Davis whip through a rollicking version of the traditional “Little Liza Jane,” or when Taylor and Vappie lay down a charming version of a Haitian children’s song, they prove they can play the old tunes, in the old way. But when they lay into new material, such as the haunting “Five Hundred Roses” (where Taylor’s banjo and Hart’s electric lap-steel trade sinuous lines) or the tragic “Simple Mind,” Taylor makes an airtight case that the banjo has been unjustly neglected by too many musicians.

“I’m not trying to be super militant with the title of this CD,” he says, “It’s just a little bit of a militant title. I want to remind black people that the banjo came from Africa, to let them know it’s not just an instrument for white bluegrass pickers.”

Over the years, Otis Taylor has amassed quite a collection of banjos, including an electric five-string, a smattering of vintage instruments and a handful of contemporary instruments made by his friend Chuck Ogsbury of OME Banjos. During the recording process for Recapturing the Banjo, Taylor and Ogsbury began to design an instrument that would have something of the tone of some of Taylor’s vintage banjos, but with modern features that made it more roadworthy than an old instrument.

“This banjo’s got to be really stable because you change climates so radically when you come to Colorado,” Taylor says. “I live in Boulder, and it’s so dry here, with very low humidity. When I tour, it seems every place else is basically very humid–or at least more humid than it is here.”

Rather than make a replica of an old banjo, Ogsbury kept the most important tone-influencing features and upgraded the other parts to increase the banjo’s stability. “Compared to what we usually do here at OME, this banjo is sort of a step back in time,” Ogsbury says. “It has a wooden rim without a heavy metal tone ring. That gives it a woodier, earthier tone. We’re also using a 12-inch pot, which also gives it a bit more depth and bass. Most banjos, particularly those in the Gibson tradition, have 11-inch pots.” Rather than use a wooden dowel stick as used on early banjos, Ogsbury opted to use metal coordinating rods. The instrument also has an adjustable truss rod.

Taylor wanted a professional-grade instrument but one that wasn’t ostentatious. Ogsbury opted to make the neck from maple, but to use a satin lacquer finish. “The inlay pattern has pink abalone, and it’s pretty basic,” Ogsbury says. “I like it–it’s not too flashy, but flashy enough. And the peghead is just a little bit simpler than the peghead we normally use on the open back.” Taylor really liked the way the banjo turned out, and earlier this year, OME introduced a limited-edition model based on it, dubbed, appropriately enough, the OTIS.

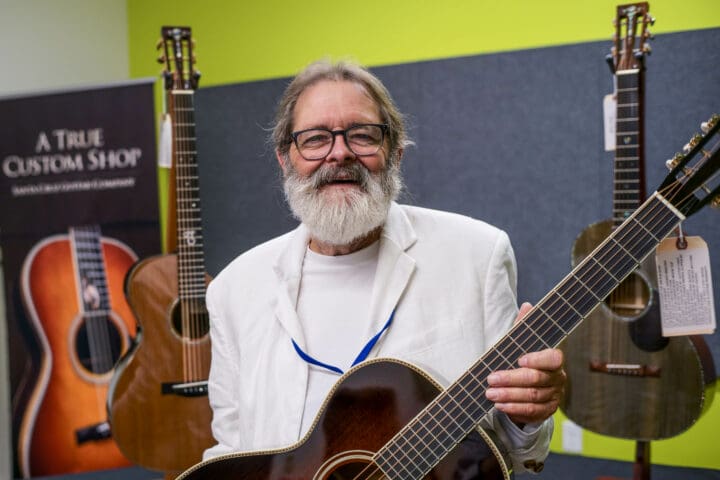

The OTIS banjo isn’t the only instrument inspired by Taylor. Last year, he collaborated with the Santa Cruz Guitar Company to come up with a signature-model guitar. “We met Otis at the MusikMesse in Frankfurt when he stopped by the booth with Gary Moore,” recalls Richard Hoover, founder of the Santa Cruz Guitar Company. “They had been touring together and they stopped by to check out acoustic guitars. Otis knew our guitars from the Denver Folklore Center and knew about our ability to do custom work.”

Taylor, Hoover and Willie Carter, in charge of artist relations at SCGC, had many discussions about things such as neck shape, action and wood selection; eventually, they came up with a design based on the small-bodied H-13. “It was coincidental that the H-13 had the basic tone Otis was looking for,” Hoover says. “He wanted a guitar that had a big sound but that was also ergonomically easy to play. He also wanted a tone that was easy to EQ and wasn’t too bass-heavy or too bright.” The H-13 is a small-bodied guitar, about the size of a Gibson L-00, but with the deeper body of a dreadnought–a combination that gives a balanced bass-to-treble response that is easy to EQ onstage or in the studio.

Taylor decided to have the sides and back made from Madagascar rosewood, which has a dark, warm tone that suits his musical style. “Otis was impressed with the environmentally responsible efforts of Madagascar in regards to wood,” Hoover says. “He also likes the idea that the wood in his guitar had African roots, which is very important to him.” They decided to make the top from Italian spruce, which was then stained a dark, caramel brown. “We wanted to capture the patina of a guitar that has been played in smoky bars for 70 or 80 years.”

Perhaps the most unusual feature of Taylor’s guitar is the lack of frets above the 14th. “Otis doesn’t play up there so he felt it was wasteful to use the metal for something he isn’t going to use,” Hoover explains. “From the building end, we found that it actually takes about the same amount of time and effort to dress the fretless section to make it match the fretted part. We thought it might save a little time, but it turns out it doesn’t. One feature I really like are the ‘OT’ initials at the end of the fretboard that honor Otis’ father, who used to paint and would sign his art that way.”

Otis Taylor’s new Santa Cruz guitar seems to have been especially inspiring. On his latest album, Pentatonic Wars and Love Songs, a typically clear-eyed take on affairs of the heart, Taylor opted to use it on 11 of the 12 tracks. His OTIS banjo makes plenty of appearances, as well. (Yes, this CD may be devoted to love songs, but, since it’s an Otis Taylor project, they aren’t necessarily cheerful ones.) The music itself still rides along on Taylor’s signature trance-like groove, but the chords and melodies have a jazzier feel than we’ve heard before–proof that Taylor is never content to travel ground he has covered before.

More and more, Otis Taylor’s stark but arresting music is being heard by a wider audience than the relatively small group of cognoscenti that have been singing his praises for the past decade. His song “Ten Million Slaves” recently appeared on the soundtrack for Michael Mann’s film Public Enemies and his composition “Nasty Letter” was heard in 2007’s Shooter. Taylor has also developed a teaching program with his wife, Carol, called “Writing the Blues” that he takes into schools around the country.

“I start by asking them to write down what makes them sad,” he explains on the program’s website. “Fears, disappointments, losses, whatever. It is just amazing to see some of these nuggets, these incredible thoughts. They are often simple sentences, but so real, so sad, so true, so pure.” Taylor feels that it’s important to give back to the community, and he’s doing his part to make sure the blues tradition continues with future generations. Taylor plays each show and records each album as if his late-blooming career has been a precious and unexpected gift. If he were to compromise his musical vision and perform in a manner that doesn’t satisfy his demanding muse, he seems to suspect, the gift can be rescinded.

“As an artist, you’ve got to try and do stuff that you’ve never tried before,” he says. “I mean, that’s part of being an artist–that struggle to come up with something new and beautiful each time. I work hard and I want my songs to be heard. I also know that some people think my lyrics are too harsh, but I can’t write any other way. They can buy my records or not, but I’m always going to sing my songs my way.”