On their Spring 2015 tour, Luke Doucet and Melissa McClelland stopped by our offices to talk guitars and songwriting. Doucet and McClelland have both worked as solo artists – independently and together – and as sidemen, most notably with Sarah McLachlan, with whom Doucet started playing way back in 1991 (he was just 19 at the time). After a while of working apart together, so to speak, in 2011 they released their eponymous first album as Whitehorse (not to be confused with the Australian metal band of the same name) and put their solo careers behind them.

They’ve released two EPs (including one in French) and two more full-length albums since then, and had a child (who’s currently on tour with them). In addition, Luke curates his own guitar festival – the Sleepwalk Guitar Festival. Check out their beautiful performance of “the sexy song” from their 2015 release, Leave No Bridge Unburned, below.

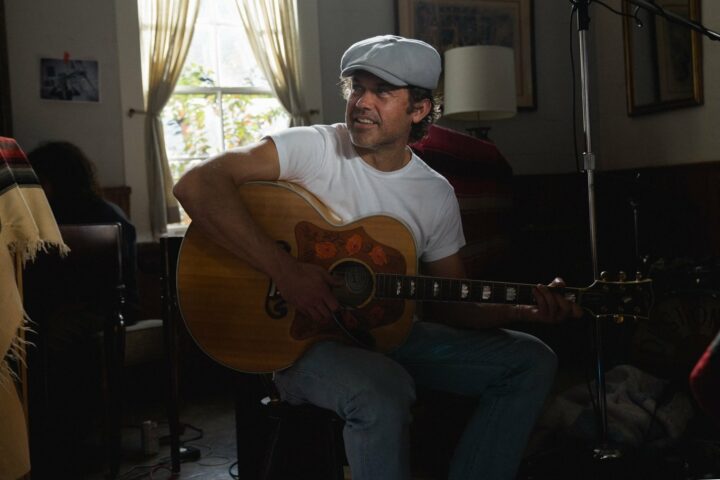

Luke Doucet: I feel sort of slightly shameful playing this guitar with all these amazing guitars watching us…

Fretboard Journal: Your guitar sounds great. And if it suits the material…

LD: You know what? This guitar [a vintage Stella, made by Harmony] is magical. It’s got voodoo in it.

Melissa McClelland: Yeah. You’ve disrespected Stella.

FJ: I assume there is a reason you brought it on tour…

LD: I haven’t done a show in 18 years without this guitar. This guitar has been on more gigs than any guitar I own. I only ever play it on one or two songs a night but I absolutely adore this guitar.

FJ: Do you play it on different songs on different nights? You haven’t played this song on the Stella, have you?

LD: Oh, I’ve never played the Stella on these songs. Typically, I would play all these songs on an electric guitar. This one usually lives in an Open E-tuning, but it’s good for anything. The neck is perfect on it. Usually they’re twisted and when they’re gone, they’re gone. This one is perfect: It lived in Vancouver, it lived in Nashville, it lived in New York, it lived in Toronto. There’s no reason that this guitar should be playable and yet for some reason…

FJ: They have no truss rods, right?

LD: No, and this is the cheapest pickup I could find in 1992 when I got pickups for it. I plug it into my little Gibson amp, turn it up and it sounds like I don’t know… I don’t even want to talk about it.

FJ: What about your guitar, Melissa?

MM: A Martin D-18, ‘73.

LD: The year of my birth.

MM: This guitar, as with all of my guitars, I’ve stolen from Luke.

LD: Just for the record, let’s just be clear about who owns that guitar…

MM: This guitar has been crushed many times, sadly. It’s like a cat. It just has many, many lives. There was one show where I stepped off the stage and a bunch of crew guys were cleaning off the stage and then one of them walked up to me with the guitar in two pieces, the neck in one hand and the body in the other. He just shook his head, “I’m sorry. Here you go.” Magically, it was fixed by Mike Spicer from Hamilton, Ontario, who is the guy. Everyone goes to him. He worked some magic and it’s just amazing because every time something happens to this guitar, I think, “Well, that’s the end of the line.” And it just always maintains that beautiful kind of mellow sound.

LD: Yeah.

It’s the Darth Vader of D-18s. It is more wire and plastic and glue than it is wood. You think, “Okay, this time when we glue it back together and fix it, it’s gonna lose its thing.” For the first five or six days [after a repair], I’m like, “I don’t know. Maybe we lost it.” And then it comes back. Two weeks later it’s like, “Check it out.” It’s like “Comes a Time.” It’s Neil Young, amazing.

MM: I love this guitar.

FJ: Is that the primary guitar you’re playing in shows or are there others that you’ve brought out?

MM: I’m playing this. I’m playing a P-bass and a Mustang [bass] and an Airline guitar. [Luke] probably know[s] more about the Airline…

LD: Well, it’s one of the Eastwood Airline reissues. So it’s a map guitar. It’s got humbucker pickups in it. It has a Bigsby. For the longest time I was trying to find a use for it. I couldn’t figure out what its job was.

On “Passenger 24,” Melissa plays this really amazing part. It sounds incredible and she had been doing it with the Harmony H-77, a three-pickup instrument. The H-77 was my main guitar back in the days when I was in my old surf punk band, Veal. I had five of those guitars. We have one left and it’s that one. But it is hollowbody and it was really resonant and kind of feedback-y; it sounded a fair bit like my Gretsch. So we were always trying to think, “Well what might be a better option?” We tried a Jazzmaster for a while. [The Harmony] was so surprising. Melissa on Humbuckers with a Bigsby, it’s perfect. How did we not try this months ago?

FJ: Creston Lea told me that he loved the sound of your Harmony…

LD: That guitar is pretty special.

MM: Yeah, it’s got some mojo. It was hard to play the first couple shows with it. I remember just kind of fighting with it and then not knowing if it was the right instrument. It’s something about the pickups, there’s something weird about it but once you get it, it feels so good to play.

FJ: Luke, you mentioned that you were trying to find “your sound” [as a player]…

LD: It has to do with kind of the instruments I’ve chosen to play and the way I hit the guitar. But I just like the idea that I don’t need to do everything. I just want to do this thing. I just want to play what I want to play.

It’s a luxury that not all musicians can afford, to be to just do what they do. When people ask me to play on something, I feel like I’m allowed to be like “Well, this is what I’m gonna play because this is how I play.”

In the session world, whether it’s Los Angeles or Nashville or New York to some degree, the description of that job is: Do what’s needed. I have nothing but respect for that approach to playing an instrument. It means I don’t get a lot of calls or sessions anymore because not everybody wants that thing.

FJ: Do you think of the Gretsch as your sound?

LD: Well, yeah, it is kind of. If I plug into a Deluxe, turn it up and turn the reverb up and plug the Gretsch straight in, I can get pretty much everything that I’m hearing in my head. There would be a lot of musical situations where that would be inappropriate. But because I’ve been focusing on the music that Melissa and I make together for so long, whether it’s her solo stuff or my solo stuff, people rarely ask me to do anything other than what [I’m known for] these days.

The interesting exception to that is working with Sarah [McLachlan]. My whole life with Sarah has been creating different palettes of colors and ambient sounds that suit her music. And my Gretsch into the Deluxe is not really Sarah’s sound. Occasionally, she’ll let me go there, but there are times when I go there and she’s like, “That’s not right for me.” I totally understand that. So I’ve had lots of opportunities to get my sort of thrills and work out and exercise the muscle of having to try and hear music through somebody else’s ears.

FJ: I read an article running down your rig that said you’re getting reverb mostly with the pedals?

LD: I was until recently. I’ve had a falling out with pedals. I was using a clone of probably a Holy Grail, essentially built into a better box. There’s a guy called Brian Duguay out of Burlington, Ontario who builds these kits, these B.Y.O.C. kits. I need a decent reverb and he built me that. I said I needed a delay pedal and he built me this sort of a bucket brigade-like, ping-pong delay. It can either be blended into one long delay or cut into two separate ones. I just use it for trying to emulate an analog delay with that decay sound. I used that on one or two songs. And I used a Switchbone to switch between amplifiers.

The Switchbone has a five or 10 decibel boost function on it. That’s all I use it for now. That’s my boost and that’s the only pedal I actually turn on and off repeatedly during the show. I run the amp hot – one or two o’clock – just enough so if I hit it hard, it breaks up. If I hit it quietly it’s relatively clean. And I turn the boost on if I want to get into sort of Crazy Horse territory a little bit.

But back to reverbs – what I recently got was a Victoria Reverberato. It’s got a tremolo circuit and a spring reverb and that’s all it is is – just a reverb and trem. I sort of got it as an experiment because I was thinking that I don’t really use a lot of effects. That’s not really the thing for me these days. But reverb is really important to me on a guitar.

FJ: The Whitehorse record certainly depends on reverb…

LD: Yeah, and it just made me think I should have the best reverb going. So I started looking for a vintage Fender tank and then I thought that was because it’ll just break down and it’s vintage and doesn’t make any sense. What about a new one? But the new stuff maybe is not as well-built. A friend said, “You should check out the Reverberato.”

MM: Who suggested that?

LD: It was John Densmore, who is a producer and plays bass with Kathleen Edwards, and is a really good friend of mine. Chris Stringer, an engineer, producer and guitar player out of Toronto, had one that he was selling, so he brought it by the studio and I plugged it in and it – I just basically went, whaaam, and it’s like, “Okay, done.”

FJ: Is the Victoria on the Whitehorse record?

LD: It’s not on the record, no. The album is just a Deluxe. It’s a Blackface Deluxe. Occasionally it is the Gibson GA-18 and the reverb is… any number of things. In some cases, it’s the tank in the Deluxe. In other cases, it’s a plate. And in some cases, there’s no reverb at all, it’s actually a mic 20 feet across the room.

FJ: Really? I was wondering about how much was the room on that record…

LD: I’m a big fan of room mics, a huge fan of room mics on guitars. Like, I think about Brian Setzer, he always insists on there can be no carpet in front of his amplifier because he wants to hear the reflections off the floor. And I totally agree with that. I love that sound.

There’s a clarity and little distortion. With the digital reverb pedal I was using, I always thought it was fine, and then I switched to the Reverberato and all of a sudden the sound of the strings and the fingers and the tunes and the speakers, everything – all those elements seemed a lot more immediate. All of a sudden there was some kind of weird distortion coming off the digital reverb pedal. Not distortion in a rock & roll distortion sense; there was some kind of thing that I hadn’t identified. What a difference.

I use tremolo a little bit too, especially on this tour.

FJ: Is that through the Reverberato?

LD: It depends. On some songs, if there’s a fast stutter tremolo, I’ll use a Danelectro Tremolo pedal that was re-housed in a proper housing. Danelectro pedals are not very durable, but they sound cool. Again, Brian Duguay re-housed my Danelectro Trem into a proper box. And I’ll use that for the stutter stuff.

Anything that has a sort of a slower, warmer tremolo sound, in my world, is off the Reverberato. Melissa is using a Line 6 Modulation monitor for her trems.

When I would be out with Sarah, I was basically doing 90-minute sets every night standing on one foot because I’m changing sounds so often. On her records, there are 14 guitar parts on every song and two guitar players unless she’s playing, maybe three. You’re jumping from part to part to part to part trying to catch all these cascading ambient things.

The other guitars that I’m touring with: I have two Falcons now. They’re both the transition era with the vertical script and the western inlay and the Filter’Trons, sort of early reissues out of the Japanese factory.

When Fender bought Gretsch, the first one I got was probably from 2001. And the second one I just found a few months ago. A friend of mine from Edmonton, a great guitar played named Jasper Smith, found it for me on Reverb or eBay. They stopped making those transition-era ones. Back in the day, I guess in ‘56, ‘57, with those appointments they would have had the DeArmond pickups. For about six months, they made that configuration with Filter’Trons, and then they stopped the Western inlay and the vertical script and they went to the classic horizontal Gretsch script that we all know. Now when you buy a Gretsch Falcon, it’s that configuration. If you want the transition-era one like the one I have, they’re a custom shop order. Forget it, not in my world… But when they reissued the Falcons in the early 2000s, the first ones they put out were the transition-era specs, which is fortunately what I got when I first ordered mine.

FJ: Have you done anything to them or are they just stock?

LD: Nothing. I just got [the second one] a few months ago and it’s like fresh bread and it turned out to be an awesome player, too, which is just luck of the draw because I bought it online.

FJ: Is the original one your favorite guitar?

LD: Yeah, I just kind of got used to it. It’s not like I played a million Gretsches. I just ordered them out of the catalog, to be honest. I got used to it and I fell in love with the sound and I know how to find the tones I want out of it.

The new one doesn’t sound exactly the same as my number one but it’s really close and it’s really playable. If I had a separate rig dialed up for a Tele that would be great, but it’s a luxury that I can’t really afford right now. I tried the Creston Tele, I tried a bunch of different guitars. Finally I just kept wanting to use the Falcon as much as I can.

On this tour there’s one song that I need to be in E-flat so I recently got a Jazzmaster. Chris Masterson, who plays with Steve Earl, is in a band called the Mastersons. He called me about two months ago because I guess he and Steve had just made a blues record. I guess he played a lot of Strat on this blues record. And I have that love/hate relationship with Stratocasters that most guitar players have; I have to have one but I never play it. Recently I got one from the Custom Shop and it’s a truly beautiful Mary Kaye and it’s really light and just plays like a dream. It’s got an Anson Funderburgh thing or a Ronnie Earl thing, just a non-Strat Strat. And it’s great.

So Chris Masterson called me. He’s like, “I just made this record with Steve and I need a Stratocaster and I think you have a great one, don’t you?” And I’m like, “Yeah, I really actually have the best one ever.” He said, “Can I have it?” And I was like, “Well… I’m not really playing it, so yeah, you can have it. Send me something.” He asked, “Well, what do you want?” I’m like, “I don’t know. Just send me something cool.” He sent this Burgundy Mist Jazzmaster, a Custom Shop Jazzmaster than I’ve been using on one song every night. It’s cool. I’m still trying to figure out if it’s the right guitar. It obviously has a whammy bar on it, otherwise I’d probably have the Creston now, actually, if it weren’t for that factor.

That’s all the guitars I have, right? Oh, I have a Larrivee parlor guitar that we’re using for one song.

FJ: What do you play at home when you’re sitting around? And how do you guys write songs together?

MM: We don’t. [Laughs.]

LD: We don’t write songs together.

MM: We write songs apart until we’re not… until one of us says let’s work on that and then we work together. I would say seventy five percent of our songs end up being co-writes of some form or another.

LD: Yeah, definitely.

MM: But not necessarily.

LD: At home I generally play a Telecaster if I’m just walking around the house. I play a Creston or I play the Shyboy just for fun. They’re small. They’re quiet when they’re not plugged in.

MM: If I’m writing a song, I find either the Martin or that Stella is great to play.

LD: Yeah, this Stella has a lot of songs in it. It’s written a lot of songs.

MM: Or the bass or piano.

FJ: The bass?

MM: Yeah, probably for this record it’s the first time I have written anything starting with bass. “Evangelina” started with that bass line which ended up being played on guitar.

FJ: How did you two end up playing together?

LD: I felt like I had this crazy epiphany the very first time I heard Melissa sing. I used to live in Vancouver and I was visiting my daughter, Chloe. At the time, I would just sleep on a futon on her floor in her bedroom. I had been receiving some mail there and I got this manila envelope with a CD in it and a postcard. It’s Melissa saying, “Hey, would you consider producing our record?”

I put the CD on and in five seconds I thought, “Holy shit, this is really special.”

FJ: I’ve been listening to both of you as solo artists for a long time, you’re basically on each other’s records all the time, was there an inevitability to Whitehorse forming?

MM: Well, that’s the word for it, “inevitability.”

It just got to the point where it didn’t make any sense musically from a family perspective, practical sense, musically, business-wise, everything. It just got to the point where it’s like this is stupid [to not form a band]. And there was a risk involved because we waited so long and we had made so many records as solo artists. As you know, fans are hard fought. You don’t take them for granted.

FJ: Your touring is just the two of you, building these loops. Is that how the record was made, too?

MM: No, no, we record in a pretty conventional way. We invite players and we usually work with several different drummers on each record. But I think on this record there were a few songs where we really tried to, you know, tap into our live show. On “Baby, What’s Wrong” there is a percussion loop that we kind of built the song around.

LD: We toyed with the idea of using loops to make a record. We thought we were gonna do that.

MM: We toyed with the idea of bringing a band on the road, too.

LD: When we make loops live, it’s different. It’s organic in its own way. It’s a different realm.

MM: There’s a performance aspect to it.

LD: And there’s a visual aspect to it. There’s something exciting about the fact that we’re recording music live onstage and we’re playing a bunch of different instruments and I think it makes for interesting music because it’s slightly different every night.

MM: The danger is palpable. You can feel the high wire act. A lot of muscle memory is involved. It’s a standing on one foot and rubbing my belly and patting my head kind of thing, the high wire act for sure.