It was a musical moment that I’ll never forget. In December 2013, I landed a gig at Ronnie Scott’s, the storied London jazz club that opened in 1959 and which has hosted the likes of Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Nina Simone, Count Basie, Wynton Marsalis, Sonny Rollins, Sarah Vaughan, and, well, basically anybody who has ever been somebody in the jazz world.

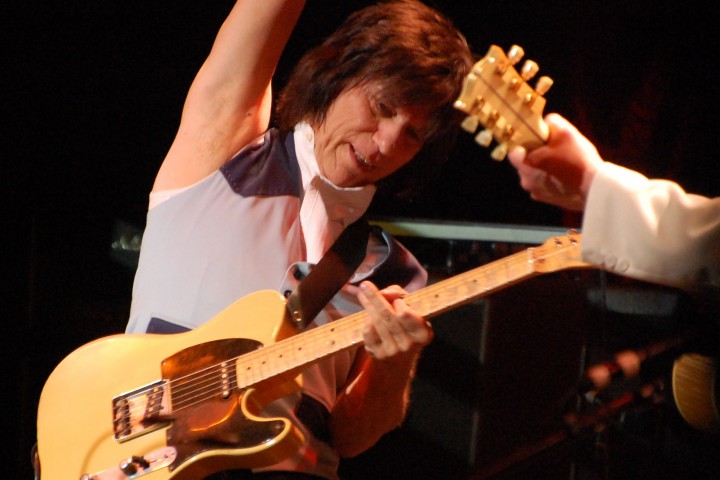

Ronnie Scott’s is also the spot where my all-time favorite electric rock and roll guitar performance was recorded: Jeff Beck’s 2008, Live at Ronnie Scott’s. In fact, do yourself a favor. Abandon reading my musings and click on over to YouTube to watch the full, two-hour performance.

You’ll undoubtedly be so mesmerized that you’ll scrutinize every moment and then return to the beginning to view the performance a second time. But on the minute possibility that you’re unwilling to let the bravura performance shove aside your other obligations in life, skip ahead to the penultimate track, the rendition of “A Day in the Life” that justifiably garnered Mr. Beck a Grammy for Best Instrumental Rock performance. Yes, I know. You’ll be returning to the performance time and time again.

Thoughts of the storied venue and of Mr. Beck’s performance swirled through my mind as I ascended the steps into the club those many years ago. As I entered, the manager greeted me and began leading me toward the stage. “Oh,” he said, “Jeff is coming to see you tonight.” “Jeff who?” I asked. “Jeff Beck.” Gulp.

Jeff Beck died at the age of 78 on January 10, 2023. As his family put it, “after suddenly contracting bacterial meningitis, he peacefully passed away.”

As we all know, Beck was, along with Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page, a member of the holy guitar triumvirate whose careers traveled through the 1960s British band, The Yardbirds. After brief stints in the band, all three, born within 15 months of each other, exited as certified guitar heroes. Clapton and Page had attained the level of artistry that would remain constant throughout their careers. Not so Beck. As Page would one day say of Beck to the BBC, “He’d just keep getting better and better. And he leaves us, mere mortals.”

Beck even stood out in The Yardbirds. Eschewing the standard blues-rock licks of his compatriots in favor of something more inventive. Listen to his solo on 1966’s “Shapes of Things.” The tune sounds like typical mid-1960s rock-pop. Then Beck enters, feedback howling over raga-like licks.

As Music journalist Alan Di Perna reported in his book, Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Beck recalled that “there was mass hysteria in the studio when I did that solo. They weren’t expecting it and it was just some weird mist coming from the East out of an amp.” Rock and roll would never be the same. Jimi Hendrix would never be the same. Remember, this was a year before the release of Hendrix’s first album, Are You Experienced, and Hendrix dropped Beck’s name during interviews early in his (too short) career.

Beck was already out in front of the musical curve in the mid-1960s. His work in the Yardbirds foreshadowed hard rock, he previewed heavy metal with the Jeff Beck Group, and invented jazz-fusion with his first solo release, Blow by Blow.

Two vignettes illustrate how intertwined Beck’s artistic restlessness was with his iconoclastic personality. First, is his fraught relationship with his Jeff Beck group compatriot, Rod Stewart. As the singer recollected in his autobiography, “The problem with [with the group], from the outset, was that it all too obviously cast Jeff in a supporting role, which he was pretty much guaranteed to hate, however handsomely remunerated. The tour was set for 74 dates over four months. Behind the scenes, a lot of people were muttering and saying, ‘This is doomed—he won’t last two shows.’ But they were all wrong. He lasted three. And then he left, saying something about how the audience were all housewives, which was a little bit rude of the old scamp.” Oh, and Beck quit the group three weeks before they were scheduled to perform at Woodstock.

Perhaps even more to the point, as Beck told journalist Kate Mossman, he turned down an offer to fill Mick Taylor’s shoes with the Rolling Stones out of certainty that he wouldn’t be able to get no artistic satisfaction from the gig. Beck had spent the spring of 1975 touring with John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, during which time the two formed a mutual artistic admiration society. As he expressed, dismissively of the Stones offer, “Playing with McLaughlin, and then the Stones – dang, dang, dang – can you imagine?” No, Beck couldn’t.

Let’s return to that Ronnie Scott’s set. Beck’s Stratocaster, the instrument he favored in recent decades, screams and swoons. He mixes the staccato with the legato, howling open string notes with pinched harmonics, and moves from whisper quiet to screeching, sometimes within a couple of bars. His right hand is a thing of wonder. He operates the volume knob and whammy bar simultaneously while fingerpicking complex and sometimes blindingly fast figures. Go ahead, check out his guitar and amp settings. Do your best to emulate Beck’s tone. Nah, you can’t. As Eric Clapton is famously credited with saying, “With Jeff, it’s all in his hands.” As music producer and educator Rick Beato recently put it, “His melodic sense! [And] every note has a different volume. Every note has a different attack, a different envelope.” Jeff Beck, Beato rightfully concluded, “is uncopiable.”

The Ronnie Scott’s set provides a good overview of Beck’s career (though, you’ll most certainly want to take a deep dive into his catalog). The opening number, “Beck’s Bolero,” a take on Maurice Ravel’s “Bolero,” document’s Beck’s penchant for incorporating classical music melodies into his playing. Beck originally recorded the tune with Jimmy Page on rhythm guitar in 1966. Yes, 1966.

The set continues to astonish. Beck demonstrates his jazz cred with Charles Mingus’s “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” John McLaughlin’s “Eternity’s Breath,” and Billy Cobham’s “Stratus.” Most poignantly, he illuminates his love and command of melody with his transcendent rendition of Stevie Wonder’s “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers.”

Beck reveals his range in two of his own compositions. In “Where Were You,” he demonstrates his ability to use artificial harmonics and the whammy bar, simultaneously, to serve a gorgeous melody. With “Scatterbrain,” he grabs a pick, something he hasn’t used for at least a couple of decades, rejuvenates “Scatterbrain,” a tune from 1974’s Blow by Blow, and plays speed-of-light fusion.

Then, of course, there’s Beck’s transcendent take on Lennon and McCartney’s “Day in the Life.” He not only conjures the full Beatles’ arrangement, but reveals the melody in a way that will come to mind every time you again hear the song, regardless of who is performing it.

The variety, the range, the contrast in techniques, and Beck’s humble stage presence expose the guitarist’s strengths and weaknesses. He was an otherworldly musician whose artistic striving and social reluctance prohibited him from following the well-trodden path into the world of rock and roll stardom.

We may not be able to please all the people all of the time, but Jeff Beck proved over four decades that he could challenge all the people, all of the time.

Well, back to my reverie. I’m now about to take the stage with it at Ronnie Scott’s. I open the second set of a night of “Classical Kicks,” a “genre-bending” series sponsored by Classical Music Magazine. The performances preceding me spanned classical, Gershwin, and Turkish music. OK, deep breath. Uh, another deep breath. I look out at the audience, trying not to focus on Beck at his table only a few feet from where I sit. I play something slow and pretty, hoping not to be compared with the virtuosos who preceded on this evening and will follow me. You can view the result here.

In the lyrics, Beck’s one vocal performance (which he disliked because his singing voice displeased him): “And it’s hi ho silver lining and away you go now …. I see your sun is shining, but I won’t make a fuss.”