There aren’t many players and luthiers as inextricably linked as James Taylor and Jim Olson. Guitar players are a notoriously fickle bunch, prone to acquisitiveness, seemingly more likely than most to covet thy neighbor’s toys, but Taylor defies the stereotype, and he has been faithful to Olson since the latter found a way to get one of his guitars into the hands of the former way back in 1989. Jim has built eight guitars for James over the years, starting with an unsolicited SJ with a cutaway. That guitar inspired an order for a non-cutaway SJ and a Dreadnought, the demands and practical needs of touring prompted a second non-cutaway SJ, then Olson insisted on giving Taylor one of each of the three James Taylor signature model SJs he built, and lastly there’s a lovely wee parlor. They’ve all got cedar tops, ebony fingerboards and Olson’s standard 5-piece laminated neck, six have Indian rosewood backs and sides, one of the signature model instruments and the parlor are Brazilian rosewood. The occasional Telecaster sighting notwithstanding, you’d be hard-pressed to find Taylor playing anything but one of those Olson guitars over the past 30-plus years.

Jonathan “JP” Prince, who started working for Taylor as a Tour Rigger and set carpenter in 2001 and has been taking care of his guitars since the start of the One Man Band tour in 2006, told us in an email, “I’ll usually take five Olsons on our ‘bus and truck’ tours. [James will] play 90% of the show on two guitars. When touring conditions aren’t extreme we enjoy bringing the Olson dreadnought out for an occasional drop tuning song such as ‘Country Road.’ We like to have back-ups in the rack during the show, and typically I’ll have one spare in a trunk as well. Jim Olson has been a consistent and unfaltering lifeline when we’ve had catastrophic breakdowns on the road. From glueing tops back together after flight damage to sending us parts and pieces, he’s always there.”

Olson and Taylor have the kind of relationship every solo builder dreams of finding. Talking with each of them it’s easy to hear their shared respect and affection — it’s reassuring to see good folks connect, and it shouldn’t be surprising that Taylor should foster these connections, even if it took a bit of a false start for Olson. Olson was a fan first, before he started building guitars. “When Sweet Baby James first came out I tried to learn everything on it,” he admits. Later, “I’m reading in Guitar Player that the two things he said he admired were a boat builder and a guitar maker. I thought, well, gee, I’d really love to show him one of my guitars. I wasn’t very optimistic that he would be impressed, but I just thought I’d like to.” He had one of those “a friend-of-a-friend”connections: Jim mentioned this inkling to Lloyd Baggs, who knew Dan Dugmore, who played with Taylor for years. “Dan was gonna somehow mention it to James,” he recalls, “Then Lloyd got back to me and said James was gonna call me, but nothing ever happened.”

Making it happen took a little more gumption than just passing word down the line, and it’s a great story, as Olson tells it, (he even dips into an uncanny impersonation of JT)…

I opened the paper one day and James was in town for a concert — this was in 1989, maybe ‘88 — a concert for the environment. James Brandenburg, who’s a National Geographic photographer, he has a lot to do with the wolves in northern Minnesota [Brandenburg took the cover photo for Taylor’s Never Die Young album], so it was a concert for the wolves and the environment. I knew James Brandenburg, I’d met him before, so I thought, “Gee whiz, I wonder if there’s any way I can bring a guitar and just show it to him.” I thought, “That’s ridiculous. I can’t do that.”

But then I got the courage up and I called the number that was listed as the promoter for the concert. A lady answered. I said, “This is gonna be a strange request. I wonder if there’s any possibility I could come down during soundcheck or something and show James Taylor a guitar.” And she said, “Oh, I’m sorry. We don’t have insurance for that. We just can’t do that.” And I said, “I get it. I understand. I should have never brought it up,” and, “I’m sorry to bother you.” And then she said, “You’re not the guy from Minnesota who makes Phil Keaggy’s guitars, are you?” I said, “Well, actually, I am. Phil’s a good friend.” She said, “Oh! I just saw him in concert last year. I just love him. Well, let me call Peter Asher and see what he says.” And she called me back within two minutes and said, “Peter said they would love to see the guitar. Just bring it down and leave it with the concierge.”

So I thought, wow, well that’s awesome.

The only guitar that I had was a cutaway, and I knew he didn’t want a cutaway. But I didn’t have anything else available; it was a spur of the moment thing. I drove it down, I left it with the concierge at the hotel, all I put in the case was, “If you have any interest, James, please call me,” and I put my number. I didn’t put any big plea or sob story or tell him I’m a fan or anything.

I got tickets for the concert that night and went to it. It was incredible. It was an acoustic concert with Mark O’Connor, Jerry Douglas, Edgar Meyer… It went on for two nights [Saturday and Sunday]. I saw the first show and I felt about an inch tall. I thought, “This guy’s not gonna want anything to do with me. Why would he want a guitar from me?” Sunday I had to go to a confirmation for my brother’s daughter in Wisconsin; I turned off my answering machine ‘cause I didn’t want to get a rejection notice on it. If somebody called I thought, oh, I’ll just take my chances. Monday came, I hadn’t heard anything. Went in to work. My shop was located in a gigantic commercial building that was housed by our church — they had the upstairs; downstairs we had a coffee house and an outreach where we did music, and I had a shop in a 1200 square foot space with three phase power and high ceilings — not behind a confessional or something — in the same building. I did janitorial work for the church to help cover my rent. I grabbed my portable phone, just in case I heard from the hotel telling me to come get the guitar. I went upstairs to the church bathrooms and I’m on my knees cleaning toilets and the phone rang and I said, “Olson Guitars,” and the voice said, “Is James Olson there, please?” And I said, “This is Jim.” He said, “This is James Taylor calling.” I said, “Seriously?” And he said, “Well, yes. Why?” I said, “Well, just a little shocked, you know? I mean, give me a second to collect myself.” He said, “Mark O’Connor and I have been playing this guitar all weekend. We’re quite taken by it. I don’t know what to do about it.” I said, “Well, golly. I’m thrilled about that.” He said, “I got a question: Why’d you bring me a cutaway?” I said, “Well, it was the only guitar I had to show you.” He said, “I don’t generally play a cutaway. Maybe I could put a plastic cobweb in there or something…” Joking. I said, “Well, if you like that guitar I can certainly make another.” He said, “Would you? Could you make me a non-cutaway? And could you make me a dreadnought, also?” I said, “I would love to, James.” And he said, “Well, what do these cost?” And I had to tell him, back then it was $2,150 for the cutaway one that I was showing him. He said, “That’s very reasonable. Let’s do that. Let’s make me a non-cutaway and a dreadnought.” I said, “How would you like that made.” He said, “I’ll leave that up to you. You make it exactly so it sounds and plays like this one. It doesn’t have to look anything specific.” I said, “Do you want the pearl on it?” He said, “I’ll leave that up to you. I think it’s best to leave that in the hands of the luthier.” He calls it “loo-thee-ay.”

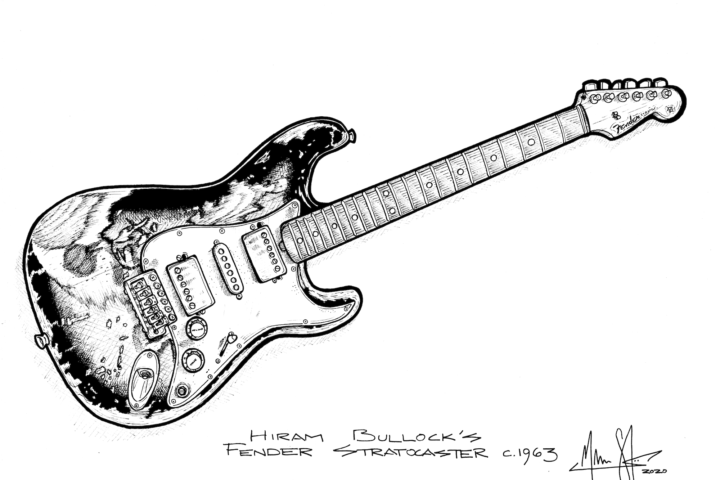

Taylor’s Olson SJ #1 (left) and #2 (right).

I’m going kinda long with this, but, bottom line, he said, “So what shall I do with this one?” I said, “I tell you what, James: pay me full price for that one, take it with you, and when I get the others done I’ll take it back.”

Fast forward: I got the other two done. It was around Christmastime of ’89. I shipped them to him. He called me back and said, “Absolutely wonderful… I love ‘em, I love ‘em. I’ve grown really attached to this cutaway. We’re going in to rehearsals, let me bring ‘em in to rehearsals and make a decision about it.” He ended up buying all three. He couldn’t give up the cutaway.

That was 31 years ago that we got that started, and he’s still using the cutaway and the non-cutaway as his main guitars, and they’ve both received extensive damage over the years — airlines crushed the non-cutaway once, had to replace part of the binding, the pearl on the top was in shards along part of it. I got it back to him in three days during the One Man Band tour. He didn’t even miss a show with it. He was on stage with Bonnie Raitt in Italy playing “#1,” the SJ cutaway, and fell on the end jack and split the end block and the sides all the way up to the neck block, and the tension on the strings separated the body in two halves by quite a bit. He was certain it was irreparable, but I got that one back together for him, too, and they’re still playing ‘em.

He always talks about the Beatles meeting walking him through a door and his life was totally different on the other side, well, that’s sort of what happened to me with him.

Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the Fretboard Journal #47.

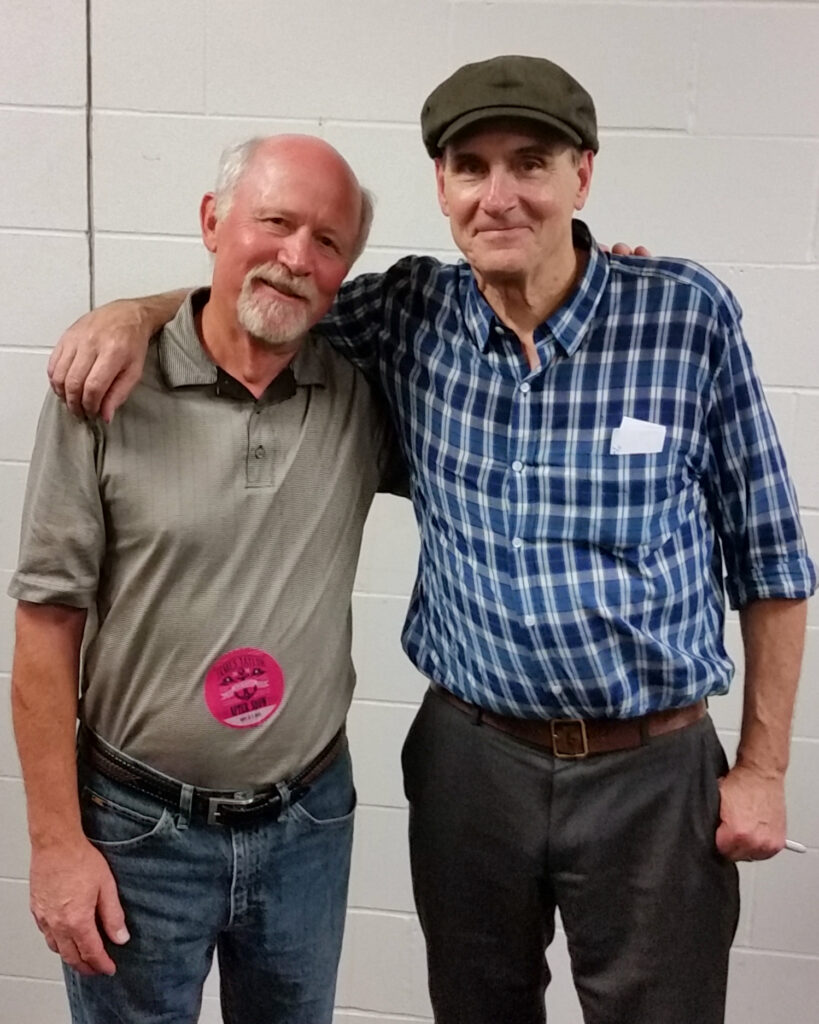

Guitar photos by Jim Olson. James & Jim photo uncredited.