Power Versus Majesty: For virtuoso picker Norman Blake, elegance and subtlety always win the day

Norman Blake’s musical ambition might be easy to articulate, but for most performing guitar pickers, it’s nearly impossible to achieve.

“I’d rather give an honest performance than a professional one,” Blake says.

Mind you, there is nothing unprofessional about Norman Blake. Playing music is the only job he has ever had, and he’s been a secret weapon for legends like Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, John Hartford and Kris Kristofferson. He played on Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken and on the blockbuster O, Brother Where Art Thou? soundtrack. In the last few decades, he has been making records with his wife, Nancy, who plays cello, guitar and mandolin, and together they have scored four Grammy nominations. So while Blake is obviously a professional, his true aspiration remains clear: His music is meant to speak to people’s hearts, not to demonstrate his virtuosity.

Norman Blake’s playing is understated and elegant. “I’m more interested in the music and the tone than I am the licks,” he says. “I want the licks to be subtle and say what they’re gonna say. And I want to put in the right things and leave out the wrong things. Just making a lick is not my goal.”

To understand what he’s getting at, listen to his two versions of “The Girl I Left in Sunny Tennessee,” first recorded in 1976 on Whiskey Before Breakfast and then again in 2004 on Back Home in Sulphur Springs. The earlier version is jangly and energetic; its rhythmic feel is pretty much the “boom chuck” you’ve heard on countless acoustic-guitar records. Blake backs his singing with fairly straight rhythm playing and occasionally throws in a tasteful fill. His solos are open and honest and serve the song well. The track is deservedly a classic.

But then listen to the 2004 version: it’s in a different league altogether. It’s a little slower and a little lower (in G instead of A), and the guitar tone is richer and fuller. Norman’s guitar and Nancy’s cello lines envelop and intertwine like plumes of smoke rising from a campfire. There is hardly a “boom chuck” to be heard. Instead, we are treated to sinuous, fluid lines where the picking is so perfectly integrated with the vocal that it simply sounds like an extension of the same thought. The guitar fills fit so effortlessly into the groove that they are almost easy to overlook. In fact, there is not such a strong distinction between the rhythm and lead playing.

Rather, it is all just part of the story, and you realize you’re in the hands of a master storyteller.

Norman Blake’s own tale began on March 10, 1938, in Chattanooga, Tennessee. When he was still a baby, his family moved to Sulphur Springs, Georgia, and even though he has traveled around the world, he has always returned to the farmhouse just down the road from where he grew up. When Blake was 16, he dropped out of school to play mandolin in the Dixie Drifters and later joined up with banjo picker Bob Johnson to form the Lonesome Travelers. By 1959, he found himself in Nashville playing with Hylo Brown & the Timberliners, touring with June Carter’s band and playing on various recording sessions. In 1961, he was drafted into the Army and stationed in Panama, where he formed the Fort Kobbe Mountaineers, a bluegrass band that was voted the Best Instrumental Group of the Caribbean Command.

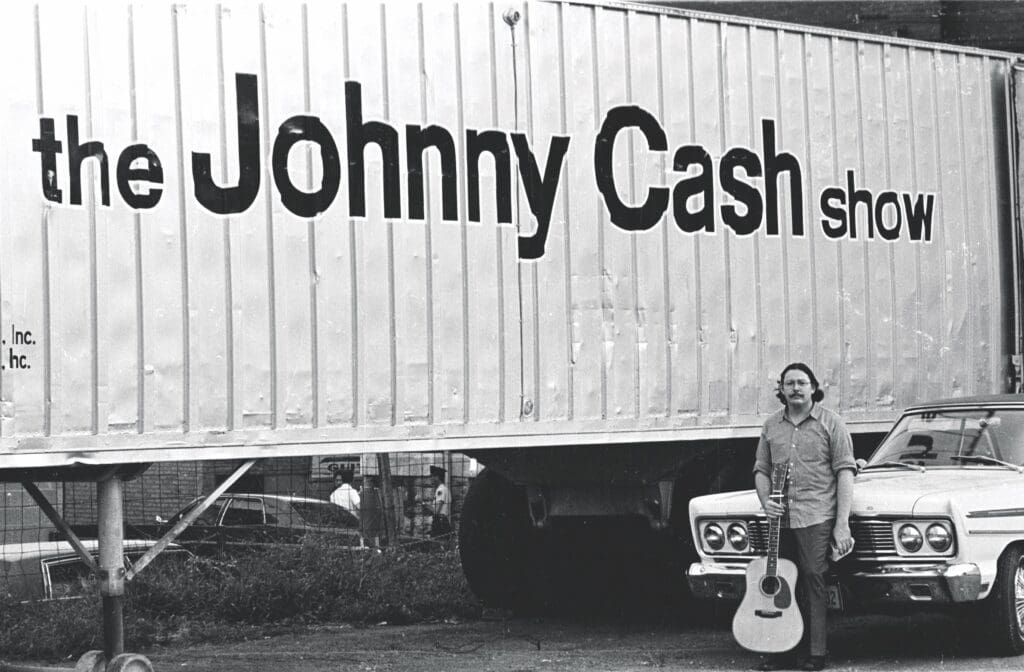

After he was discharged in 1963, he paid the rent by teaching guitar and playing fiddle in a cover band. He soon got a job with Johnny Cash, and his touring and recording tenure with the Man in Black introduced him to a new circle of admirers. Over the course of the next decade, he was in the studio working on vital records such as Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, Joan Baez’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and John Hartford’s Aereo-Plain, or hitting the road with Kris Kristofferson’s band. Although he is best known these days as a guitar player, Blake made his bones as a multi-instrumentalist playing mandolin, fiddle and Dobro. “I’ve been playing that instrument all my life,” he says of the resonator. “I probably performed more commercial sessions as a sideman on Dobro than anything. That’s the instrument that I consider if I’m just going to play country music.”

In late 1971, he recorded his debut, Home in Sulphur Springs, the first of more than 20 solo records. Not long after releasing his first album, he met Nancy Short, a classically trained cellist with rock n’ roll leanings. Somehow they found a way to mesh their musical styles, and they started touring together in 1974. The following year, they got married – as Nancy says, she “loaded up the truck and left town with Norman” – and they have been together ever since. Blake had first made his reputation backing up other musicians, and when he set out on his solo career, he knew he needed an exemplary backup player of his own. Just as he was a secret weapon for people like Johnny Cash, Nancy became his secret weapon.

“She has always had a knack for coming in and going along with what’s there,” he says. “She had orchestra training when she was young so she’s used to finding a part, and that’s where she excels. She likes to explore and she will do some things that are not totally straight down the gun barrel to everybody’s thinking because she has had orchestral training. If she’s going along playing on the guitar and she decides she wants to play some kind of a running line or something like that, she’ll do it.”

Nancy Blake is a deep listener. In conversation and in nature, she listens through the words and surface sounds to hear their inner meaning. This may be one reason why she is the perfect accompanist. “I took to heart the saying that the soloist is only as good as their accompanist,” she says. Her use of cello was unusual when she first started playing it in a folk and old-time context, but she quickly proved it had a place at the table.

“There was a lot of really loose picking sessions down on Second Avenue at the Old Time Picking Parlor,” she explains, talking about the store started by Tut Taylor and Randy Wood in Nashville in the early 1970s. “One day, Tut let me sit in and play with them and Charlie Collins. I’d put in a bass line, and they’d point out and say that’s a good idea. I thought I was being real original, playing the lines behind the fiddle tunes. It was cool to be able to go up into the different ranges and go back down into the bass ranges, too. That was before I knew about Otto Gray and the Oklahoma Cowboys and people like that who played cello in the way-back time. There was a span of time where there wasn’t a cello around, but I came to find out that they were pretty popular during the pioneer days. You could throw them in the back of the wagon, and they took up less space than a bass.”

Norman Blake was one of the first pickers to recognize the tonal potential of vintage guitars. To put “vintage” in perspective, consider that Blake was born in 1938. A Martin dreadnought from that same year is just about the most desirable vintage guitar you can own. When Blake recorded his first LP in 1971, these guitars had only recently made the transition from “used” to “vintage” – a transition helped along by a lot of Blake’s associates, including Tut Taylor and Randy Wood.

“If you’re gonna play music from that Depression era, there is something about those old instruments,” he says. “That’s what the old songs were played on, and it sounds good on them. It just fits the time. There are good new instruments, but they are from another period. They sound like a later time. Some of them are quite good and, in some ways, can be superior to some of the old ones, like the intonation, fingerboards, the neck angles and things like that.

“But when you really want to go back to a certain world, then you have to go into a little funkier kind of mode and be more accepting of the old ones. Because, for what they may lack in slickness that the new ones have, they surpass them in character. I like an instrument that has a lot of tone character to it – one that really sounds unique or just sounds so good in a certain way that you cannot ignore it. And that is what the old ones have.” Blake often lists his instruments in the album credits alongside the musicians, engineers and other contributors. Whiskey Before Breakfast, his 1976 classic for Rounder Records, credits a 1934 Martin D-18, which started something of a cult for that particular model. Shacktown Road lists no less than 17 instruments used on the recording, ranging from Nancy Blake’s 1832 cello by Charles Jacquot to a 2002 guitar made by Robert Altman of Colbert, Georgia.

But Blake’s not a vintage-guitar purist. He plays a new guitar made for him by Altman and speaks highly of the guitars he plays by John Arnold and the Santa Cruz Guitar Co. He also worked with Martin to create the limited-edition 000-28 Norman Blake, which was released in 2004. This unique guitar combined a 14-fret 000 body with a short 24.9 scale length and a 12-fret neck. This allowed the bridge to be moved closer to the center of the top, which in turn gave the guitar a stronger bass response and a more open tone.

Ultimately, the heart and hands of the player matter more than the spruce, rosewood and mahogany. Songwriter Jerry Faires , who’s composed some of Blake’s favorite songs, says, “Norman’s drive to simplicity, while never losing sight of the core melodic content of any tune, sets him apart from a world of ‘hot pickers.’ I told him he was a great inspiration to a guy like me, with little natural ability, for that very simplicity, and he said, ‘Well, I try to leave out everything I can.'”

To achieve that level of simplicity, of course, requires a lot of work and effort. Blake says he practices every day to “maintain my basic repertoire and learn a little, maintain my technique.” Think about that: Blake was already playing guitar back when Harry S. Truman was president, and he still practices every day, perfecting the basic elements that are sacred to every guitar player.

He also invests a lot of time in getting the best tone from his instruments. For each individual guitar and mandolin in his collection, and there are lots of them,” Blake says, “I’m not a collector, I’m an accumulator.” He determines the uniquely best combination of string gauge, string type and brand, even the pick material and thickness that will get the best tone out of that particular instrument.

“I try to figure out what the instrument is good for and what I’d want to use it for,” he says. “Whether you can stand up and really honk it, or whether you have to just sit down and approach it a little more intimately. There are a lot of guitars you could sit down and take that quieter approach with and really do some good work, but there are some when you really need to just stand up and perform … then that’s a little different ball game. Each instrument has a function, and to try to make them all sound the same is a mistake. There’s no point. You might as well just have one guitar. So you have to let every one be what it is and let it find its own way. Then you find out how you play that one, and what kind of strings and things you need to use on that one, to get the best out of it. Or what seems to satisfy your own soul.”

Nancy Blake is not quite as much of an instrument accumulator as Norman is, but she knows what she likes. “I’m into instruments, too, but we’re into them in different ways,” she explains. “I search for what suits me in a given phase of my ongoing development. Once I get one that I decide to really hunker down on, then that’s it. I know which guitar in this house is mine. I know which cello I like to play and which fiddle and which mandolin.” In selecting her instruments, Nancy looks for “a tone that goes straight to the heart,” although in truth, that phrase may equally apply to everything she does. “I think that part of a musician’s job is to soften up the hearts of people so they can receive a better message.”

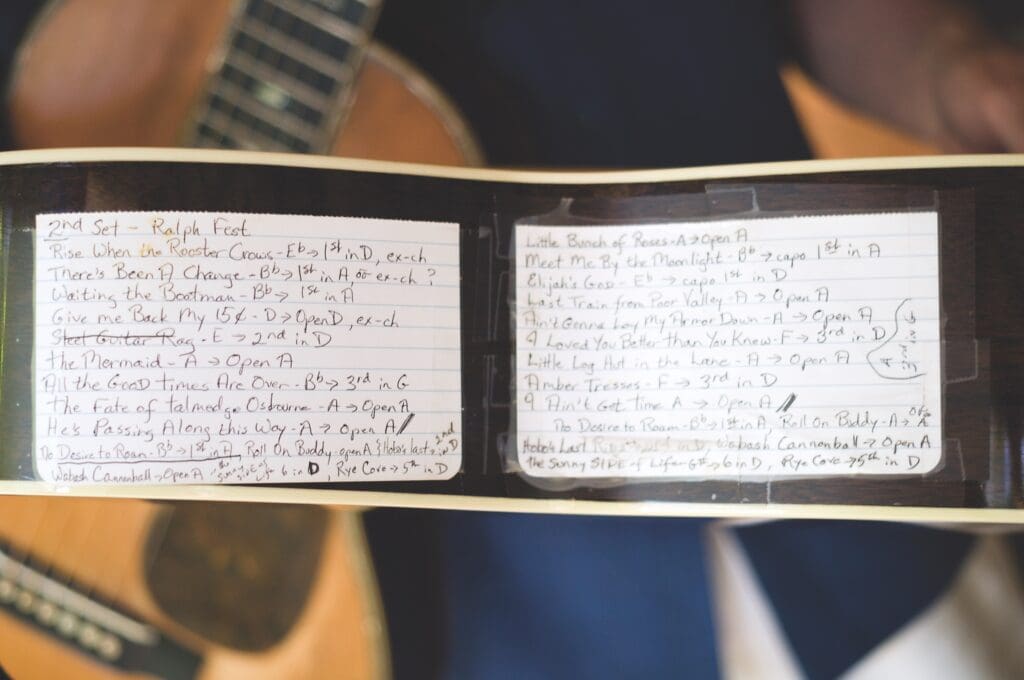

Lately, Norman and Nancy Blake have been devoting their time to performing duets. After taking a break from performing together, they released The Morning Glory Ramblers in 2004 and then Back Home in Sulphur Springs in 2006. “Morning Glory Ramblers was the first record that Nancy and I had made in several years,” Blake says, “and we thought, just like we go out and play shows and sing the old songs and play our guitars, we’ll just go stand up and do these songs the old-time way, with not much frills as far as adding anything. There’s a little bit of overdubbing on that one but very little. We basically wanted to record the core sound of what we were doing on the stage. We also wanted to document ourselves because that’s just what we sounded like at that point. Back Home in Sulphur Springs was done a little differently. We did a little more embellishment and a little more production than we did on the Morning Glory record.”

One of the highlights of Morning Glory Ramblers is Nancy Blake’s “Men with Broken Hearts,” a spoken-word song originally done by Hank Williams under his alter ego, Luke the Drifter. “I’d never done a spoken-word piece before,” she says, “and of all the Hank Williams songs, that was my favorite. Also, in the back of my mind, it kept hammering in on me that there was some man who needed to hear that with a woman’s voice. You know, sometimes people can hear something from a woman’s voice they can’t hear from a man’s voice. I thought the message of that thing was so good that I’d take a swipe at it.”

Even with embellishment, the Blakes’ approach to recording is straightforward and honest. “We don’t fix things,” Norman says. “I’m not one of these people that believes in fixing it in the mix. I like to go straight through with a take, all the way through, and usually keep the first or second one – the first one I can live with. Hopefully the first one, because I feel that the further you go, you may slick it up, but I think for what you gain, you lose as you go along and you get tired. You can refine a nice performance into something that’s really stale when you’ve done it that many times.”

Back Home in Sulphur Springs includes a relatively rare example of Nancy Blake playing lead mandolin. Her take on “The Star Spangled Banner” is possibly the sweetest and least bombastic version of the American national anthem ever recorded. “I heard [fiddler] James Bryan play it that way,” she says. “It was from maybe an 1830s arrangement that he had rooted out from the fiddle world. I think it’s an antiquated version, but it’s worthy of presenting for the case I was trying to make … that it’s a better tune than you usually hear it. And to rethink it just a little. It’s a grand tune. People need to remember that sometimes the true grandeur of nations is reflected in delicacies. Not everything big has to be oppressive and heavy. Like power versus majesty: There is a big difference.”

Except for a few years in the Army and a few years in Nashville, Norman Blake has lived his whole life in the neighboring towns of Rising Fawn and Sulphur Springs, Georgia. He still lives there today. When he refers back to the old family acts, you must remember that it’s the music he grew up with on 78s and on the radio.

“Everybody had an old windup Victrola and a stack of records,” he says. “My grandfather recited poetry when I was a child. He was a 19th century-type guy, and the old songs were so much in that style that I just became washed over by all that.”

Blake understands the old-time country music as well as anyone. He lived the life, and in some ways, he still lives that life. His songs tell stories that reflect his experience, classics such as “Ginseng Sullivan,” “Church Street Blues,” “Billy Gray,” “Green Light on the Southern” and “Last Train from Poor Valley.” Ginseng Sullivan was a real person. The “reverse curve” in the tracks “about three miles from the Battelle yard” was a real place.

However, he is also willing to speak about current events, should he feel the need. “Don’t Be Afraid of the Neo-Cons,” from Back Home in Sulphur Springs, is a classic example. In a style reminiscent of those good old Southern Democrat songs of the FDR era, by way of Woody Guthrie, “Neo-Cons” speaks both directly and subtly. The literal message is unambiguous and a pretty clear statement of Blake’s own beliefs, but the delivery and context exhibit a depth, subtlety and sense of history that may bypass the casual listener.

“That was something that was done in an old-time way and done rapidly,” he explains. “We didn’t have but about 10 minutes to cut that on the end of a session, and just sort of read it down off of the page where I had written it. It was just my take on what Nancy and I find not acceptable in today’s world. A political song is not the normal thing I do, but I said long ago that if I ever had something that I wanted to editorialize on, that I would not hesitate to get on my music as a soapbox. Not to run it over people when they’ve paid me to entertain them, but to put it on record if I felt the need to editorialize. This was one of those times.”

Blake’s original songs sit very comfortably alongside such traditional songs as “Columbus Stockade Blues,” “The Little Log Hut in the Lane” and “The Girl I Left in Sunny Tennessee.” His tunes may well become part of the traditional repertoire within a generation or two. Blake also records new songs by songwriters like Pattie Bryan (“Empress of Ireland,” “On the Banks of Lake Pontchartrain”) and Jerry Faires (“Precious Memories Was a Song I Used to Hear,” “D-18 Song”).

Faires offers a telling story about Blake’s attitude toward the old and the new. “When I received the pre-release copy of Morning Glory Ramblers, I spoke to Norman, telling him how humbling it was to find ‘Precious Memories Was a Song’ on that list of old classics. He replied, ‘Well, Jerry, I believe it belongs on that list. I hope I didn’t hurt it none.'”

Norman Blake doesn’t tour much these days. After 50 years of touring, the road seems to have lost much of its charm. But he and Nancy do make the occasional festival appearance and concert gig, always to high acclaim. And to make up for their lack of stage appearances, they have stepped up their recording projects, and since the turn of the century, they have released six CDs, including this year’s Shacktown Road, which also featured their old friend, Dobro wiz Tut Taylor.

More than 30 years after Norman Blake recorded his debut, Home in Sulphur Springs, he and Nancy recorded its sequel, but the title of that follow-up, Back Home in Sulphur Springs, is a bit misleading. If you just listen to the album’s perfectly played, down-home picking, honed by five decades of life on the frets, you’ll realize that Norman Blake has never really left Sulphur Springs at all.

The Setup According to Norman Blake

Figuring out the best way to set up an instrument – and the best way to use it – is determined by trial and error; as Norman Blake says, “that’s what guitar and mandolin players do.” Guitar and mandolin players also tend to get a little obsessive about the specific details of their favorite player’s setups, and Blake’s setup method is one of particular interest to his many followers. “I tend to set my guitars up fairly low and I don’t use real heavy strings,” he explains. “I’ll use heavy bass strings. Sometimes like the low E, I’ll get pretty heavy with that. It depends on the instrument, but I’ll go as high as a .060 on some guitars. But it’s usually more like .056s and .058s. Mostly I use light gauge, with maybe a little different bass string or top string or something like that. I never use anything heavier in the middle than .025 on the third string or .034 and .044 on the fourth and fifth strings. I never get up to medium in the middle. And I use more .012s and .016s on the first and second strings. Rarely sometimes I’ll use .013 and .017 on the trebles, but not much. “I use some nickel strings. I use some white bronze. GHS is my endorsement, and they’ve been my favorite string for years. I don’t think there is any other string for what I do. I use white bronze, I use bright bronze, I use Dynamite Boomers, normally an electric-guitar string, on certain acoustic guitars. The GHS string reminds me of the old days. It has more of a fundamental sound to it. You hit it, the note comes out, and it’s a big note. It isn’t as zingy a string as the D’Addario. I use D’Addario some, too, on some things. If you’ve got a guitar that is seeming a little stiff, a D’Addario can benefit you there. But if you’ve got your action down low and you want a big note with a low action, seems like the GHS works for me. “I use various picks depending on the instrument and the string setup. If I’m using plastic picks, I use Jim Dunlop. The lightest I would use is 1.14 [mm]. I use 1.5 a lot. I also use a 1.5 D’Andrea some. On the dreadnoughts, I tend to use tortoise picks. “I like a good, straight neck … I don’t like them with a lot of relief in them. I like a little wider spacing if I can get it on the older guitars. I’m not a fan of the small necks. I like a neck with a little bit of width and sometimes a little bit of heft to it. It just depends on the instrument.”

Excerpted from the Fretboard Journal #8, originally published in November 2007. Photos by Thomas Petillo. Top photo of Blake with his Gibson Century of Progress: Christi Carroll