Like a lot of us, London’s John Stubbings is a bit obsessed with guitars. After years of sub-par instruments, he made the leap to a nice Martin, which soon led to another, better Martin. And, soon enough, his guitar purchases multiplied and he found himself browsing the inventory of Dream Guitars and The North American Guitar, eventually commissioning a custom guitar from an independent luthier (Dave King). Stubbings went beyond just amassing a nice collection, however. At some point in his obsession, he started to document it.

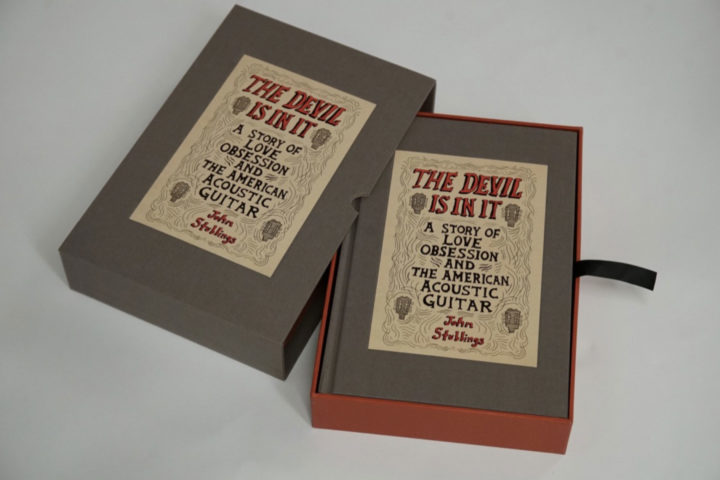

Stubbings has just released The Devil Is In It: A Story of Love, Obsession and the American Acoustic Guitar, a completely unique, limited-edition keepsake book that’s equal parts memoir and an oral history of the modern guitar movement. The slip-cased, deckled-edge volume – filled with commissioned hand-drawn art from FJ contributor Drew Christie – is unlike any other “guitar book” you’ve ever seen. It harkens more to the famed, limited edition, letterpress editions of the famed Doves Press than anything you’d find in the aisles of Barnes & Noble. It also more than a few FJ connections (Stubbings attended the first Fretboard Summit we produced, where he landed several interviews). We decided to touch base with the author to hear about how this exquisite book came to be and, of course, to talk gear.

Fretboard Journal: When did your guitar obsession begin?

John Stubbings: I can pretty much pinpoint it precisely to March, 1995 when I had just turned 40 years old… It was the day I finally bought my first Martin guitar, a late ‘70s 00-21. That led me to start reading up on Martin history (Carter’s The Martin Book, etc.) and a few months later I’d traded up the 00-21 for a 00-42…

The journey into true obsession didn’t happen in a thunderbolt but like the proverbial, “How do you boil a frog…” I realize that back in ‘95 was when the “frog that had just been slipped into a pan of lovely… warm… water.” There’s also a U.K. vs. U.S. point here: I’d been playing guitar on-and-off since I was 14 and obviously knew that Martin and Gibson existed (I was a voracious live music fan, record buyer and played in various folk bands) but, like most amateurs in the U.K., American brand guitars were the instruments of dreams and for professionals… remember only in 1959 did the U.K. post-war embargo on U.S. luxury imports end and by then U.K. amateurs were mainly buying Eko, Hofner, Levin and Yamahas… my first guitars when I was 14 or 15 were a Japanese Epiphone and then an Eko Ranger 12-string. U.S. brands were just out of reach – emotionally and financially

That day in March, 1995 was actually the first time I’d held let alone played a Martin. An amateur playing a Martin, assuming they had the money, was overstepping the mark.

I’m also pretty certain that Clapton Unplugged was a bit of a nudge towards owning a Martin, as was the fact I was a comfortably off baby boomer with the means to buy one.

FJ: At what point did you decide to write an entire book about your guitar habit?

JS: In 2006, I’d asked Dave King, a well-regarded U.K. luthier, to make a bespoke parlor guitar… his specialty. It would have been my 15th guitar. I had traded up and bought and sold quite a few in the intervening 10 years after buying that first Martin but the Dave King Parlor would be the 15th guitar in the house.

He reckoned it would take about 18 months, but it was a troublesome build – as related across the book – and, as we reached June, 2014, I still didn’t have it. I thought the story of the guitars commissioning and often tragic-comedic lack of progress, linked to my obvious descent into G.A.S., might make an interesting monograph…

But, as I drafted it out what was going to be called No. 179, the allotted serial number of the Dave King guitar, I began to wonder how had I contracted such an unreasonable passion for the guitar in the first place. And, as I started tracking down, talking to and interviewing other “accidental serial acquirers,” I realized I wasn’t alone: Almost everybody had guilty secrets, most were adept at deception and quite a few demonstrated the obvious traits of the addict. So the book expanded in scope and was shaping up to be called, Two Guitars: A True Story of Obsession, Addiction & Deception.

As I dug deeper into the history of the guitar, I realized how the modern acoustic that had such a hold over me (and clearly many others) was an American invention, and one that is clearly the defining instrument of our age.

FJ: This book is both very personal, but also historical. How did you balance that?

JS: I still wanted to tell the story of the Dave King guitar. My initial beta readers found it variously funny, sad, endearing and revealing… of both me and the builder. But I also wanted to tell the complex/compelling story of the acoustic guitar: How it usurped not only the piano, but other portable, fretted “folk” instruments like the banjo, the mandolin, the ukulele… all of which were often much more popular than the guitar. [I also wanted] to explore the role it had in culture, politics, civil rights… the elements that made me want to do my U.S. roadtrips.

While I was on the road, I got into the habit of sitting down at the end of every day and writing up my notes – every day I’d meet people, visit key places, visit guitar stores and knew I needed to keep track of all these conversations. I’d talked to lots of friends about doing the trip and many said to keep in touch. I wrote my notes at the end of every day as a blog. At 10 p.m., I’d start typing, upload a few photos and post around 2 a.m. (8 a.m. in London). People started feeding back how much they enjoyed it and forwarding the blog to others which encouraged me to craft it. I pulled them altogether at the end of the first trip into From the Big Apple to the Big Easy.

I drafted a second, 120,000-word version of the book – what was now called Guitar: A History of Love and Obsession– and sent it to my new U.K. and U.S. editors. They both felt it needed something to pull the two elements of “History of Guitar” and “Dave King Guitar” together and suggested using my roadtrip as the glue. I was able to daisy chain the trip through the birthplace and home of the guitar with the history of the guitar and its own journey from New York across America. As one reader remarked, “If I was getting a bit bogged down in guitar history I knew there was a funny bit about Dave coming up or I’d meet someone like Dame Meghan or the mayor of Clarksdale.

FJ: A lot of musicians think of guitar books / magazines as “guitar porn”… pretty pictures of guitars along with some description text. You took a more artful approach with original drawings. Why did you decide to go that route and how did you pick your illustrator?

JS: I wanted to produce something that would do justice to the story of the acoustic guitar. As I say in the Preface, the book is a love story about the guitar and I wanted to produce something that would do justice to the object of my love. I imagined the final book being bought primarily by people who share that love and obsession… and I wanted a book that could physically warrant its place alongside a vintage Martin or bespoke Kostal.

When I approached potential publishers in both the U.K. and U.S., they were interested in the concept but ultimately they either wanted another piece of guitar porn – glossy color photographs and refreshed versions of the same old captions or a semi-academic book akin to Shaw and Szego’s Inventing the American Guitar or Philip Gura’s C.F. Martin and His Guitars (1796-1873). There’s nothing wrong with that. They know what sells, but that means they often produce another version of existing books… that’s not what I wanted to make.

When I talked to publishers about hand-binding, linen cased covers with a blind embossed cover illustration, letterpress-quality typography, hand-tinted color illustrations, raw fore-edge art quality paper and a boxed and slip-cased edition they reminded me that they were in business to make money! I soon realized that I’d be funding the production myself with little chance of breaking-even let alone making a profit. I could just about afford to produce a hand-bound private edition of 300 books… and that’s what I ultimately did.

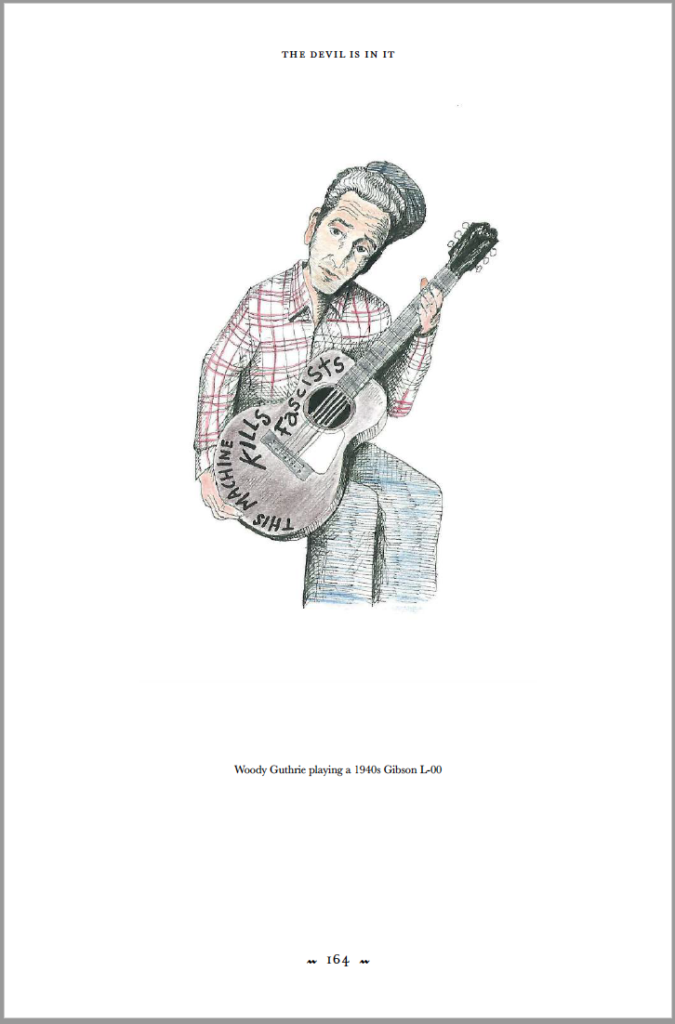

The internet means that quality photographs of virtually every guitar that’s ever been made is a click away. But I did want to “illustrate” my story. I’d initially considered wood cuts or illustrations that brought another dimension and I recalled a Fretboard Journal feature on Drew Christie (FJ #30). Coincidentally, I’d had a Drew Christie pen and ink portrait of C.F. Martin above my writing desk for a while and I wrote a letter to Drew. I emailed him. I wrote again. Nothing. I eventually got a reply in late 2016. He was interested but snowed under with projects and suggested that I “drop by when I was next in the area.” Since I live in London and Drew in Puget Sound, that wasn’t going to be easy. But we eventually met in the Summer of 2017. We spent hours talking about potential subjects to illustrate and when he showed me his 106-page long hand illustrated book ‘Drew Christie’s Illustrated Encyclopedia of Folk Instruments,’ of which only one copy exists, I knew I was talking to the right guy. We agreed a shortlist of five or six potential subjects for each chapter – but I agreed to leave the final choice to Drew – no roughs, no samples, he’d just send me the finished illustrations when they were done.

When I saw the final illustrations, I knew they had to be put into the book as separate color plates on art quality paper. When I asked the bookbinder how much putting sixteen separate color plates, printed on art paper, into each of the 300 books would cost I had to lie down for half an hour. He explained that it would cost that much because it involved 4,800 separate operations, each one taking about two minutes. It would take one person four working weeks to complete the task!

FJ: What were your first steps in doing research and gathering interviews?

JS: I read a lot. I already had substantial guitar reference library of about 50 guitar books but I steadily filled the gaps, re-read them, indexed them, cross-referenced them and made notes of the conflicting accounts. Only when you work out what you know do you fully appreciate how little you really know. I ended up with a list of about 400 substantive questions. From “What did John Deichman actually do at Martin?” to “When did the guitar first arrive in Hawaii?” I started interviewing what guitar collectors I knew in the U.K… who connected me with more… many more.

FJ: Beyond the historical facts you uncovered, you actually took a months’ long roadtrip through the U.S. What were you looking for? Who did you talk to?

JS: I started having phone conversations with people like George Gruhn and Matt Umanov and soon realized I’d have to sit down with them in person. That was when I knew that I needed to do a roadtrip of some kind. A friend told me not to book a back-to-back schedule of pre-arranged meetings and instead just follow my nose. The really interesting stuff often happens by chance; someone will suggest you talk to a friend. The interesting people often have informal gate-keepers: Both Gruhn and Umanov were very evasive about whether they could spare me any more than half an hour. Stan Jay’s children and widow didn’t initially want to meet, but I spent a cathartic afternoon with them at a much diminished Mandolin Brothers on Staten Island.

Bill Luckett – the mayor of Clarksdale, Mississippi – wasn’t even on my list. But he was one of the most interesting people I met and I spent the best part of two days with him. He got me a visit to the Mississippi State penitentiary, but only on the proviso that I didn’t write about it. I got to him via a retired lawyer in Oxford, Mississippi, who connected me with both the Mayor and Libby Rae-Watson, who knew and took guitar lessons with both Furry Lewis, Sam Chatmon (Mississippi Sheiks) and Big Joe Williams

FJ: Of all the guitar personalities you met, which encounters stick out the most?

JS: Unsurprisingly, given my quest, George Gruhn. [He was] not easy but ridiculously generous with his time and contact list. Or Eric Schoenberg. It was fascinating about the OM and he and Dana’s collaboration with Martin, but equally interesting about his early days in Greenwich Village, Moses Asch of Folkways Records, Izzy Young and Dylan. And Dave Crosby… I met him at your Fretboard Summit and got to play his Woodstock D-45

FJ: Having published a massive book about your love for guitars and your self-proclaimed G.A.S., where are you at with your guitar passion now? Are you even more rabid about buying guitars? Or did this book help you get it out of your system?

JS:I’ve calmed down a lot. To be honest I’ve fallen back in love with playing more than collecting, although like most serial acquirers I never saw myself as collecting or as a collector per se. Collecting normally involves some objective and I just acquired instruments that I liked. Unfortunately for my bank balance, I liked a lot. If I’m passionate about anything it’s the importance of the guitar in our culture.

FJ: Since you’ve spent so much time on both continents: How does the U.K.’s guitar culture vary from America’s?

JS: I’d refer back to how my own obsession began, and the fact that the famous U.S. brands were quite rare in the U.K., even in the early ’70s. Only a few guitar stores in London’s “Guitar Alley” – Denmark Street – stocked Martin or Gibson and they were ludicrously expensive even for a semi-professional, let alone an amateur. And even an amateur with money in the ‘70s or ‘80s would probably be embarrassed to have a Martin or a Gibson. As you know Bert Jansch usually played a basic Yamaha FG-150, or a relatively modest John Bailey guitar.

I remember a young American Catholic priest visiting a youth club we were playing at in the late ‘70s. He turned up to strum a few campfire ballads and pulled a Martin D-35 out of a case. We were just amazed that a) he’d travelled from America with a Martin; b) he would have a Martin and play so poorly; and c) he could afford such an exotic guitar. He gladly let our group’s guitarist play it for the rest of the evening and said his traveling partner had an even better Martin back at the rectory. Our guitarist considered converting to the priesthood if a Martin was a standard perk.

Things started to change in the later ‘80s and I think Clapton Unplugged had a big effect on the broader quality guitar market in the ‘90s and the ubiquity of Martin and Gibson in Britain.

The vintage/pre-war guitar boom from the ‘60s through to the present day was a small thing in the U.K., down primarily to lack of supply and as that market boomed in the U.S., British enthusiasts were out-priced.

One of the issues I address in the book is, given the importance of British bands and artists globally, the lack of a substantive British guitar industry in the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s and even today. I think it all stems back to the post-war years and what happened after the skiffle boom. To paraphrase from Chapter 18 …

“The British guitar industry after the war, stifled by permits, super-tax and limited demand, never got a chance to develop beyond a few small scale builders of dance-band style archtops. Post-war, Britain was on its knees and therefore guitars were a very low priority. By the time of the skiffle boom in the mid-1950s it was too late for a British guitar industry to establish itself, so instrument importers like Selmer turned to Europe. And by the time Britain returned to real economic growth America had cornered the quality/premium guitar market and German, Italian and Japanese makers were fighting it out for the mid-price and budget segments.

When the US luxury goods import ban and 100% luxury tax was finally started to be lifted in mid-1959 skiffle music was fading in popularity and electric beat music was on the rise. Young electric players were either putting basic pickups on an existing acoustic skiffle guitar, buying cheap imposters of American solid-body instruments made in Czechoslovakia and Japan or, if they wanted the same guitar as played by both McCartney and Lennon while in Hamburg, an entry level Club 40 hollow-body electric from Hofner.

Emile Grimshaw Jnr, who had started in the ’20s playing banjo in British dance bands and with his father established a banjo and guitar making business, was still around and by the early ‘60s producing a small range of solid-body guitars. In 1959 the Grimshaw Short Scale was a well-made but truly awful sounding instrument and its name and plain styling gave it no chance against a superb looking and sounding guitar with a futuristic namelike a Fender Stratocaster in Fiesta Red – even though at £100 the Fender cost almost twice that of a Grimshaw.”

To order The Devil Is In It, click here.