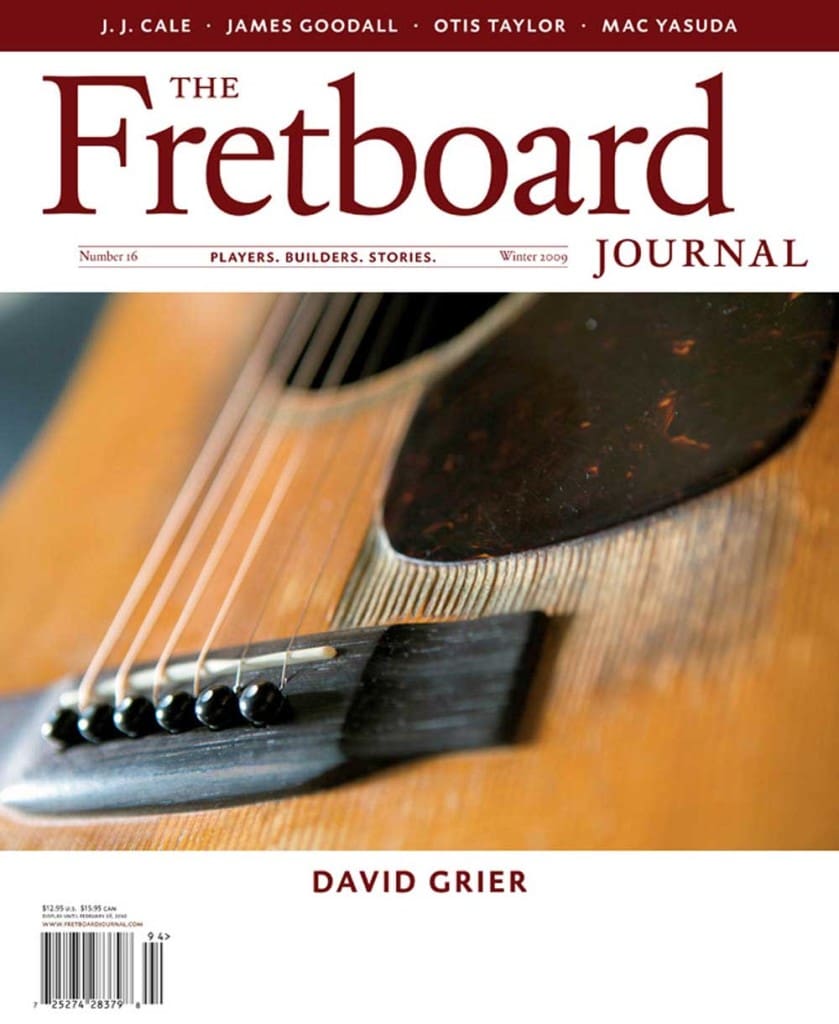

Over the course of another 128 pages, issue 16 of the Fretboard Journal brings you a solid dose of the finest coverage of musicians, instruments, and builders. Highlights include profiles of the legendary songwriter and guitarist J.J. Cale, fingerpicking master David Grier and luthier James Goodall, Thurston Moore’s interview with sonic experimenter Michael Champan, as well as stories on bluesman Otis Taylor, Eastman Guitars, and much more…

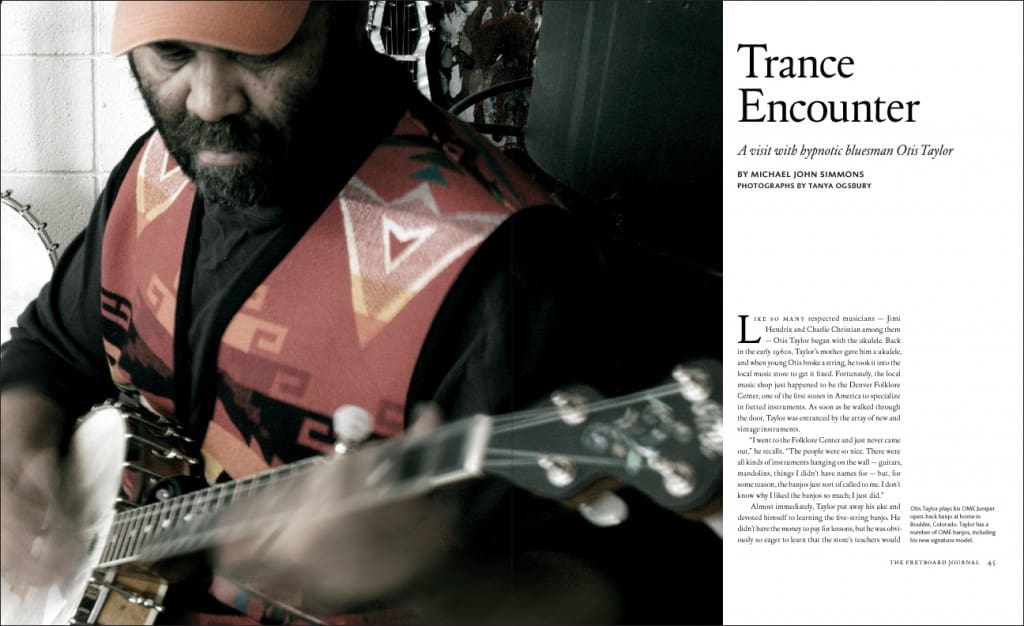

Like so many respected musicians–Jimi Hendrix and Charlie Christian among them–Otis Taylor began with the ukulele. Back in the early 1960s, Taylor’s mother gave him a ukulele, and when young Otis broke a string, he took it into the local music store to get it fixed. Fortunately, the local music shop just happened to be the Denver Folklore Center, one of the first stores in America to specialize in fretted instruments. As soon as he walked through the door, Taylor was entranced by the array of new and vintage instruments.

“I went to the Folklore Center and just never came out,” he recalls…

Michael John Simmons profiles Otis Taylor. Read the full article here.

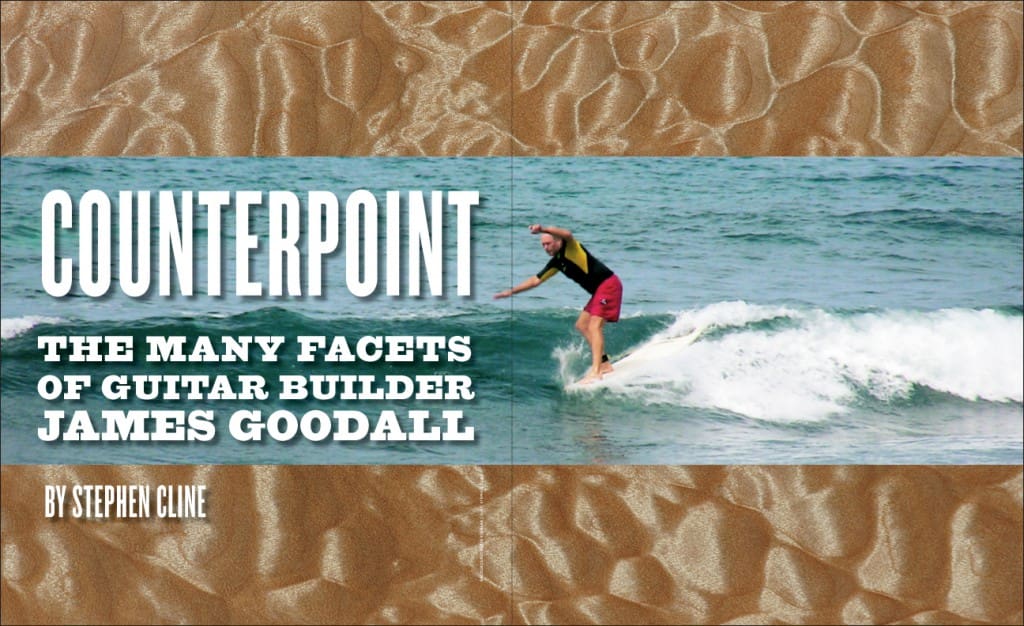

After a pleasant dinner on the lanai, James and Jean Goodall had us gather around the laptop. They had brought pictures of the properties they were considering on the Northern California coast. It was bittersweet seeing them; it meant our friends were moving away from Hawaii.

From the perspective of Google Earth, Fort Bragg is a small town on a coastline that looks as if it has been chewed by a snaggletoothed monster, with dozens of miniature coves and beaches sheltered by low stony cliffs. The Goodalls once left the Southern California beach town of San Diego to spend eight years there. And now, after 16 years here in Kona, they were planning to return–uprooting their guitar-making shop and setting it up again amid the windswept beauty of that rugged coast. As I write, the Kona era of Goodall Guitars is closing.

It’s not quite pau (finished, as we say here in Hawaii), but, given the circumstances, I am inclined to reminisce.

Luthier James Goodall sits down with writer Stephen Cline.

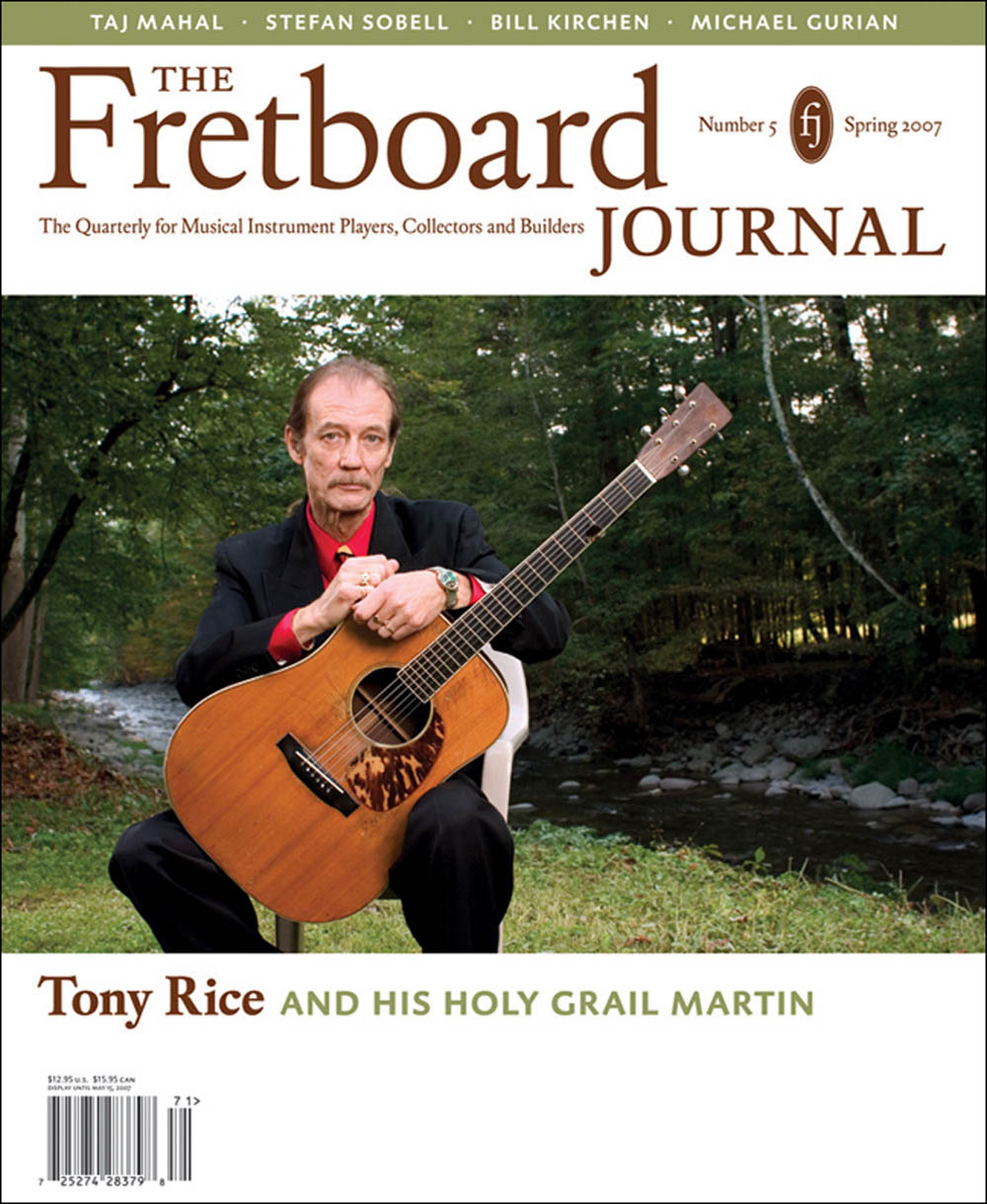

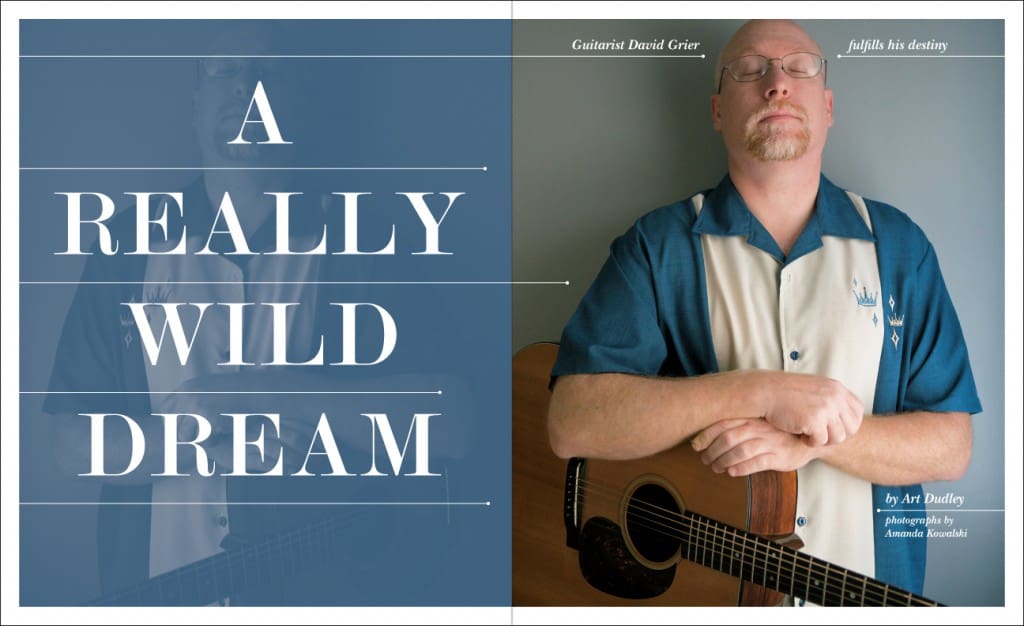

David Grier can scarcely hide his excitement as he tells the story. A few days earlier, on a Saturday evening in July of 2007, the guitarist stood in for the late Charles Sawtelle during a reunion of the fabled bluegrass band Hot Rize. But this was no festival set or club date; the one-off gig was a private party in Beverly Hills.

Entertainer Steve Martin had invited 80 friends to dinner at his home, and only the band and a few attendees knew the real purpose: Martin’s “surprise” wedding to writer Anne Stringfield. The guest list was appropriately starry.

“So the guests start coming in,” Grier says, “and one of the first people through the door is Martin Mull. Martin Mull looks in my direction, like he recognizes me, and he comes right up. ‘You’re David Grier! I love your music!’ And I said, ‘Well, gee, thanks.’ And he says, ‘Please, you’ve got to do me a favor,’ and I’m thinking, well, maybe he wants me to get him an iced tea or something. Instead, he asks, ‘Please play that song that goes da-da-daa,’ and I realize he’s singing a song of mine called ‘King Wilkie’s Run.’ That was when I knew he meant it–he really knows my music, and he wasn’t just being polite….

“And that was the tone of it. Throughout the whole time, these people were so kind and so well mannered. I mean, here’s Tom Hanks, standing a few feet away, applauding whenever I take a solo! It was like a dream. A really wild dream.”

Regular FJ contributor Art Dudley explores flatpicking legend David Grier’s dream state.

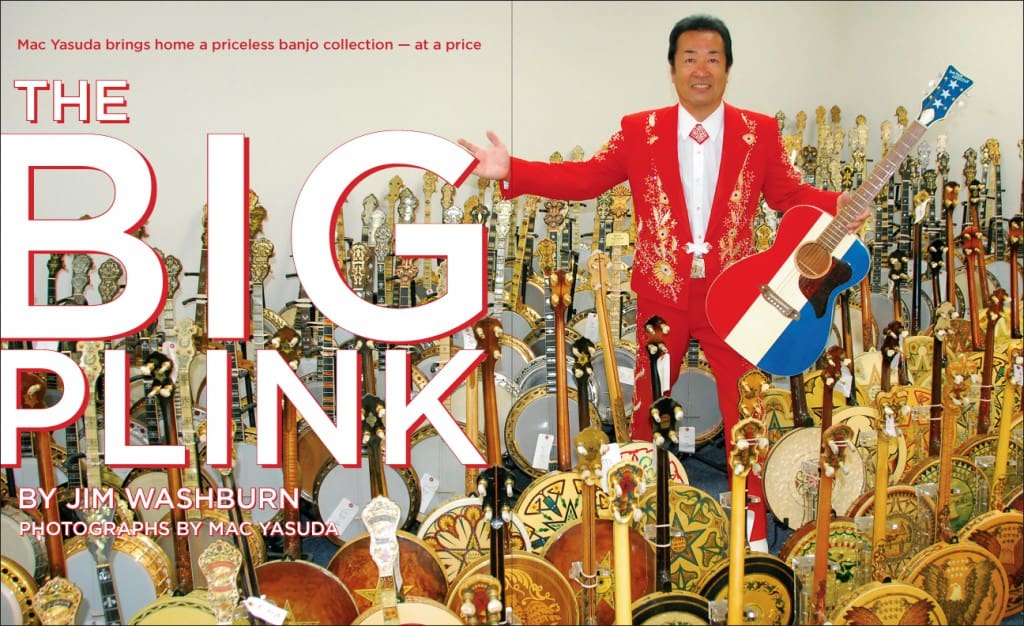

Upper-tier, classic American banjos of the 1920s and 1930s display a level and variety of craftsmanship virtually unmatched in the annals of stuff. Anywhere you look on these instruments, some craftsman has been there first: hand engraving a filigreed design in the metal rim; hand painting a fleur-de-lis on a headstock; hand carving an ornate ebony elephant’s head at a neck heel, replete with little ivory tusks; hand etching patriotic scenes into celluloid fret markers.

People sure must have had a lot of hands back then. What were they thinking, the artists who spent weeks toiling over these details? Did they wonder if their anonymous efforts would be appreciated, if they would inspire the musicians to greater heights? Did they wonder where their banjos might be in five–or 50–years’ time?

Even the most farsighted and glue-addled of them couldn’t have imagined that, nearly a century after these masterpiece banjos were made, the best of them would be piled in a dark, dank, corrugated-metal barn half a world away amid the rice paddies of Japan’s Chiba Prefecture. Or that they’d lay forgotten there for more than a decade, until someone finally came along to rescue them–someone wearing an orange hazmat suit.

“It was the worst smell ever in there,” Mac Yasuda recalls. “There were dead rats, rotting newspapers. We opened one banjo case, and it was overgrown with green moss.”

Jim Washburn tells the story of Mac Yasuda’s priceless banjo collection.

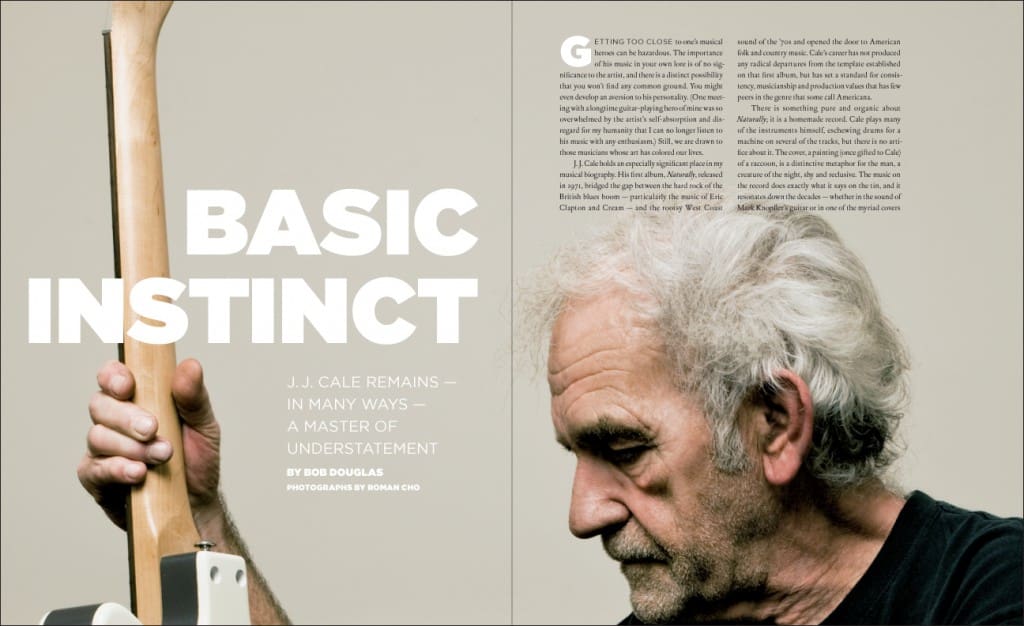

Getting too close to one’s musical heroes can be hazardous. The importance of his music in your own lore is of no significance to the artist, and there is a distinct possibility that you won’t find any common ground. You might even develop an aversion to his personality. (One meeting with a longtime guitar-playing hero of mine was so overwhelmed by the artist’s self absorption and disregard for my humanity that I can no longer listen to his music with any enthusiasm.) Still, we are drawn to those musicians whose art has colored our lives.

J.J. Cale holds an especially significant place in my musical biography. His first album, Naturally, released in 1971, bridged the gap between the hard rock of the British blues boom–particularly the music of Eric Clapton and Cream–and the rootsy West Coast sound of the ‘70s and opened the door to American folk and country music. Cale’s career has not produced any radical departures from the template established on that first album, but has set a standard for consistency, musicianship and production values that has few peers in the genre that some call Americana.

There is something pure and organic about Naturally; it is a homemade record. Cale plays many of the instruments himself, eschewing drums for a machine on several of the tracks, but there is no artifice about it. The cover, a painting (once gifted to Cale) of a raccoon, is a distinctive metaphor for the man, a creature of the night, shy and reclusive. The music on the record does exactly what it says on the tin, and it resonates down the decades–whether in the sound of Mark Knopfler’s guitar or in one of the myriad covers of Cale’s songs. Yet, few have been able to replicate that mysterious quality–that effortless precision–so often identified as “laid-back.”

Bob Douglas profiles the legendary guitarist and songwriter J.J. Cale.