Nels Cline’s New York apartment building stands out a bit from the older structures that occupy the rest of the block, thanks to its very modern orange and gray color scheme. The lobby is filled with activity this morning: to my left, an elderly couple collects their mail; to my right, a woman rushes past them toward the elevator, nearly bowling over two small dogs as their owner lazily shuffles down the hall; the doorman in front of me mumbles under his breath in a thick accent, surely concealing choice words. I wondered: Do these people have any idea they share an address with one of the world’s greatest living guitarists?

When I first met Nels in the summer of 2015 he said something rather strange, something that stuck with me for quite some time, rolling around in my head like the last gumball in a jar. It was just after Wilco’s set at Seattle’s Marymoor Park when I posed a question about one of his instruments. He stopped me and said, “I don’t know anything about guitars, trust me!” I was shocked. Surely that can’t be true.

In a sense, he’s right. For Nels, the minutiae that may fascinate the everyday gearhead just doesn’t seem to matter all that much. Things like a particular year, veneer fretboards or the chip in a coveted overdrive pedal aren’t nearly as compelling as what the thing can do for him. And while forum experts argue about vintage instruments and effects, Nels is busy figuring out how to expand his tonal palette with them.

Sitting down with him here in Brooklyn, I remind him of what he said that evening after the show. With a laugh, he quickly reaffirms his stance as we dive into the subject of guitars and guitar ephemera. He warns me, “There’s a pattern here in this story that’s basically complete ignorance.”

Like many of us, the decision to play guitar came about as a result of loving music. He cites the Rolling Stones’ High Tide and Green Grass, its gatefold photos of shearling collars, red corduroy pants and big guitars leaving quite an impression on his younger self. And he loved Hendrix, but didn’t want to follow too closely. “I thought he was a magician, you know, shamanistic, and that it would actually be disrespectful and fatuous of me to think I could even get close to that.”

He cut his teeth on a single pickup Teisco Melody, which his parents purchased from a student at the Los Angeles City School District where they both taught. Together with his twin brother, Alex, on drums, he remembers playing “mostly trills and lots of feedback,” sliding the guitar neck up and down the side of the amp. He admits, “I didn’t know how to play!”

That guitar is tucked away somewhere, maybe even here in the apartment, buried under any of the other 40 or so guitars he keeps in a makeshift crawlspace. Most of the instruments here aren’t being used heavily at the moment—the on-duty ones live either at Wilco’s Loft in Chicago or at his former residence in Manhattan.

Nels retreats to his music room, then squeezes through a tiny sliding window that leads out into loft storage. It is absolutely packed with guitar cases. I follow as he snakes his way through the cramped space, pulling cases from piles five or six high, handing me instrument after instrument with the enthusiasm of a nostalgic Gold Rush prospector remembering his claims. He has more instruments than he knows what to do with, and to that end, his new motto is: “I’m never buying another guitar.”

Deadpan, he jokes, “So far, I’ve almost stuck to it.”

One of the first instruments he hands me is a walnut-colored Gibson ES-335 that his parents bought new in 1971. As the story goes, his aunt passed away suddenly after choking on a piece of meat and left everything to Nels’ father, who saw how serious the boys were about music. The family took a trip to West L.A. Music to buy decent instruments with the inheritance.

For someone so closely associated with Fender instruments, it’s surprising to learn that Nels was “a die-hard Gibson guy” at the time, thanks the influence of Dicky Betts, Neil Young, Paul Kosoff and Duane Allman. “I was going to play a Les Paul come hell or high water,” he reminisces. Sadly, expectation did not meet with reality, where a chunky neck and unbearable weight left him feeling underwhelmed. “I thought, ‘This is just a horrible guitar.’” Of all the other instruments there that day, Nels gravitated toward this 335, which fit right in with his chosen “not-calling-too-much-attention-to-himself” aesthetic. He loved the neck, the darker sound and even the size of the body, and so the 335 went home with Nels that day. Notably, this 335 has the embossed pickups common at the time, which he claims were “the most uncool thing ever,” although he’s aware that they’re now considered to be very cool indeed.

The guitar’s original trapeze tailpiece is long gone and replaced with a stoptail, something that Nels regrets, wishing he “still had those strings behind the bridge.” Not knowing any better, he was talked into the modification by an unscrupulous guitar tech who then messed up the first time, leaving crescent-shaped scars on the body. And because the tech insisted jazz players like high action, the guitar was unplayable when he picked it up. Horrified, a young Nels would spend the final moments before that evening’s school band performance in his mother’s car, feverishly trying to make his guitar playable. “They totally screwed up my guitar and I didn’t know anything… I said, ‘I can never trust anyone with my guitar again.’”

Despite the disappointment, this brown 335 eventually got straightened out and would remain his “one good guitar” through the early 1980s. It can also be heard during the solo on “Either Way” from Wilco’s 2007 release Sky Blue Sky.

Digging through his stash, Nels pauses now and again to show off a few choice pieces. Knowing how much I love sparkle finishes, he reappears with a 1960s Eko 500 and a recent Moog Lap Steel, both of which are hypnotic and underutilized. He then hands me a ’30s Dobro lap steel, aka “the world’s heaviest instrument.” No amount of warning could have prepared me for the weight of that metal body. Still, it’s totally original and very, very cool.

Sifting through gig bags, he calls out, “Here’s one for you!” He fishes out a black case from the bottom and hands it to me. Inside is his sunburst 1966 Fender Jaguar, the guitar that set off his “offset” obsession in the 1980s. Having never bonded with the Strats he used with both BLOC and Julius Hemphill, a bourgeoning love of Sonic Youth convinced him a different Fender model might be just the thing he needed.

“Every time I saw a picture of Thurston Moore playing a Jazzmaster I thought, ‘Wow, that guitar looks so cool!’”

Unaware of the differences between the Jaguar and Jazzmaster, he scoured the Los Angeles Recycler until he found the first thing close to it.

“I picked it up and it was love at first feel,” he remembers, and he happily paid the asking price of $325. Surprisingly, it fit the bill at jazz gigs and recording sessions alike, thanks to a fantastic neck pickup that fooled listeners into thinking it was “some slick, fancy guitar.”

Though Nels is well known for using Mastery Bridge hardware, it’s worth mentioning that he never changed the bridge on this Jaguar. “It always kinda worked,” he offers. Upon inspection, it’s plain to see the guitar is set up with a good amount of neck angle, and the low E saddle has been notched for extra insurance against the string popping out under heavy play.

That Jaguar would see him through most of the ’80s and into the ’90s, but eventually it dawned on him that the Jaguar “wasn’t rocking quite hard enough” with its short scale and bright pickups. The hope for more low end and a tighter feel led him straight to the Jazzmaster. “I realized the extra string length would give me that tension even though I’d lose the high D [Jaguars have 22 frets, Jazzmasters 21], and those pickups just have beef.”

Nels trots out his two “New York Jazzmasters” for my perusal. The first is a sunburst ’59 with a gold anodized pickguard. It was once broken in half lengthwise through the body, and much of the nonoriginal finish is starting to wear away under the heavy play of its owner. The guitar has both the Mastery bridge and vibrato installed, and the neck is notably wide. Without a means of measuring the nut, I ask his preference. “I’m not super neck-sensitive––I can pretty much get around on anything.”

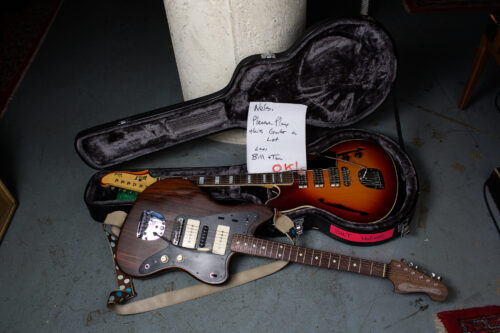

The other Jazzmaster is a “Band-Aid colored” parts guitar built by John “Woody” Woodland of Mastery Bridge fame. The guitar is outfitted with a kit neck and Seymour Duncan PAF-style humbuckers disguised in Jazzmaster covers with dummy poles, which allows him to “have his cake and eat it too” on recording dates where quiet operation is a must. “I’ve noticed that a lot of people who do avant-garde music really are sensitive about 60-cycle hum… I’ll bring, like, three or four guitars and a lap steel and give people choices, and I swear to God here in New York everyone picks this guitar with the PAFs.” This one’s equipped with a Mastery bridge and a vintage Fender vibrato, and most importantly, cartoon stickers of his wife, Yuka.

As for new acquisitions, there’s his new Collings, which he’s very excited about, becoming more and more animated as he tries to pull up a picture on his phone. The guitar is a customized LT360-M with a vaguely Les Paul Jr. shape, but with an offset waist. It has a refreshing look, sporting bright red plastics and a pickguard that’s reminiscent of Atomic Age designs on a white-blonde finish, a special request that Nels calls “kind of circus-looking.” It has a Mastery bridge and vibrato as well as two of Lollar’s amazing Gold Foil pickups.

Guitars are coming out of cases at a rapid pace now: here’s a new D’Angelico that plays like a dream; an old “Valco-y” Dobro with a black-and-white art deco finish that finds its way onto recording after recording; there’s even a cool short-scale sitar made from a Teisco Tulip body and a Silvertone neck, perhaps the most functional electric sitar I’ve ever played. With an “Oh yeah!” Nels produces the ’62 Fender Jaguar he calls “Kristen,” named after androgynous model Kristen McMenamy, whose picture happens to be plastered onto the top of the guitar.

But what Nels really wants to show me is his ’60s Gibson Barney Kessel. He was turned on to the model by who else but Jeff Tweedy. Nels estimates Jeff has “five or six of them.” Nels only has one at the moment. This model has always been one of the big ones in my view, with its rich red sunburst finish and those pointy devil horns that upend the classy guitar status quo of the jazz scene. The guitar is his first-choice axe when touring with Julian Lage. Strung with 13s, he congratulates me when I bend the G string.

Granted, this is exciting in its own right, but he insists that the neck pickup is the real star here. Installed just a week prior to our meeting, the unit comes from maker Bob Palmieri, a name Nels mentions in hushed, reverent tones. The pickup is both darker and quieter than other humbuckers, boasting an incredibly round and sustained sound. I have to agree, I haven’t heard anything like it. Palmieri previously worked on another instrument for Nels, dubbed “the Moth”—a blonde import Les Paul Special copy. Palmieri gutted the guitar, then installed his own pickups and special electronics with a parametric EQ and added a wooden bridge.

Nels closes the final latch on the Kessel’s big red Calton case, then scuttles off to an upstairs room where he keeps––you guessed it––more guitars. He comes back with an armful of what are clearly acoustic cases, and at some point during all of this it becomes evident that Nels holds a certain affinity for acoustic instruments over electrics. I wondered aloud, “Is it fair to say that you’re more excited about acoustic guitars?”

“Not more excited,” he responds thoughtfully, “but I know their abilities. I really understand each one’s uniqueness.” To Nels, acoustic guitars have more personality than their electric cousins; without need for effects or amplification, they are judged by their own merits.

His small stable of acoustics includes a well played-in ’62 J-200 (yet another Tweedy-influenced purchase), which he doesn’t bring down because it’s “boring.” It does, however, possess essentially the same neck as his Barney Kessel, which makes it one of his go-to guitars. There’s also his ’52 Martin 00-17, purchased for $250 back when Martins were considered “campfire guitars,” paid off in tiny increments from his Rhino Records paychecks. There’s also the ’78 Taylor 12-string that he bought new, and an old Florentine Kay Kraft.

The air becomes heavy as he opens the lid of another case. He calls this 1937 National resonator “the most mojo-laden guitar of all time,” and he definitely has a point. Rusted-out and bedazzled, the guitar has a lore that he spins for me. “This guy had painted his name on it. He put rhinestones and star stickers and all of this stuff all over it. It has, purportedly, a portrait of his wife painted on the guitar, and he just rusted it out. Every time the rust got too bad he’d just put gold paint over it, and then that would wear out.”

Luthier Tom Crandall acquired the guitar from its original owner and then rebuilt it, having to reposition the fretboard to make the guitar play in-tune. It retains its original biscuit cone, which is impressive considering how much it’s been played, and it still has the jute string strap installed by the former owner. To play this guitar is to know the most mellow, sullen tone you’re likely to hear from a metal-bodied instrument; it is deep, round and storied. Shaking his head, he insists, preposterously, “I don’t deserve this guitar.”

One of the most interesting guitars in his collection is also the easiest to overlook, but once you pick up this featherweight 1940s Harmony Sovereign and note the Baxendale label in the soundhole, you’ll realize it’s something special. Athens, Georgia, luthier Scott Baxendale performs full “conversions” of Harmony and Kay guitars. Scott replaced the bridge, reset the neck and fully rebraced the guitar, and let me tell you, the transformation is amazing. My jaw dropped at the first strum; I have never heard a sound like that from a Harmony—rich, open tones from a truly incredible instrument. Nels takes a some time to strum a few notes, and it almost feels as though I’m caught between secret lovers stealing glances from opposite ends of the room.

Effects

Touching briefly on pedals, Nels takes on an air of diplomacy, saying, “I don’t mean to be self-congratulatory, but I seem to know how to use pedals.” He likens discovering sounds to stumbling around a darkened room, but I’d wager it’s a room he’s familiar with. “When I hear what a pedal does, I can generally work it into my world.”

Along with Jazzmasters, Nels is a guitar player characterized by his judicious use of effects, from the lauded Klon Centaur to the outrageous ZVex Fuzz Factory. His ultimate necessity is the old Electro-Harmonix 16 Second Delay, which he uses to create beds of reverse leads and chirping sci-fi mainframe computer sounds. For him, only the original will do, even if it’s falling apart onstage. Nels has five of them, but only three are functional.

When touring with Wilco, he can bring virtually any pedal he likes, but when it comes to his own music, his setup has to be compact. His “New York Board” now hosts a Seymour Duncan 805 in place of his Centaurs, a JHS Muffuletta, a custom-painted ZVex Fuzz Factory, his trusty original Boss Vibrato and a Whammy WH-1, which is much smaller than any of the reissues.

Nels has also helped develop a signature pedal. Simply called GOO, ToneConcepts has crafted a pedal truly worthy of the man who named it. According to Nels, it is something “like an old Marshall Guv’nor, but with more gain,” as well as glow-in-the-dark knobs and a look inspired by the classic sci-fi movie The Blob.

Amps

When it comes to amplification, he really only needs two things: low midrange and headroom. Struggling to figure out his sound early on, things finally clicked once he discovered the glory of dark guitar amps. “When I finally played an amp that didn’t have too much treble, I realized that was what I wanted.”

Most boutique amps just won’t work for Nels Cline––too glassy, too snarly and strident. And while he can get around on just about anything, he’d still prefer any number of small-batch, hand-wired amps in place of his dreaded nemesis, the Silverface Twin Reverb. Having dealt with backline Twins for years, Nels has a theory: “Nobody that ever owned them maintained them.”

When he has the option of using his own gear, he still takes out the now-discontinued ZT Lunchbox Club model with a 12-inch speaker. He’s also eager to discuss a new favorite from a company called Studious. Each amplifier named after innovative electricians, Bryant Howe builds them one at a time, with an emphasis on simplicity. Nels adores his 21-watt Moseley model, which has a decidedly less-trebly personality. “An amp where I have to turn the tone all the way up? This is my kind of amp!”

When he plays with Wilco, he sticks to his signature Schroeder DB7 (now dubbed SA9). Its 40 watts of output is both loud and dark, and possesses “bizarrely incredible” sustain. It’s also built like a tank, but uses incredibly expensive, matched vintage tubes, which might be its only drawback. “Whenever anything goes wrong with it, which is pretty rare, it’s usually a tube issue. Forget about it, I have to be in a big, famous rock band to put tubes in that fucker.”

“I hope you get there someday,” I offer.

“Yeah, I’m praying. I’m doing some chanting,” he says with a laugh.

See also:

Mood Swings — Nels Cline’s most audacious project is also his most beautiful

Strings Attached — Nels Cline’s favorite ensemble jazz albums