The post-Gidget surf boom had its own eponymous soundtrack: surf music. It came in two varieties. There was the heavy Dick Dale-invented instrumental form—songs you could drink and fight to. Surfers, most of them, loved it. Then there was the softer, brighter, Beach Boys-style vocal pop. Surfers, again, had strong feelings. “We hated that crap,” big-wave terror Greg Noll recalled. “These record company guys would come around to the surf shops handing out free Beach Boys records, and two seconds after they were gone we’d be tossing the records out the back door into the dumpster.”

Before Dick Dale, before the Beach Boys, there was just music to surf by. West Coast jazz was the hep wave-rider’s music of choice during the mid-to-late-’50s. In 1958, John Severson opened Surf Safari with Henry Mancini’s cloud-splitting Peter Gunn theme, and the audience response blew the roof off of several dozen California auditoriums. The same year, alto sax player Bud Shank scored Bruce Brown’s film Slippery When Wet, resulting in a first-of-its-kind surf movie album soundtrack. Shank returned in 1960 to provide the score for Brown’s Barefoot Adventure, and the that LP sold over 10,000 copies—respectable numbers for a jazz recording even today.

Surfing and jazz then went their separate ways. Boomers were taking over the sport, and there was no question as to their music of choice: rock and roll. In 1960, a Washington state instrumental band called the Ventures crashed the Billboard charts with a snare-popping number called “Walk Don’t Run.” In their matching suits and ties, the Ventures looked more like the Four Freshman than Jerry Lee Lewis, but pop music at that point was in a lull—Elvis had gone soft, the British Invasion was four years down the road, Motown wasn’t yet a hit-making machine—and these Northwesterners rocked harder than anybody on the charts. When “Walk Don’t Run” peaked at number two in September, it augured well for other rock instrumental groups. Many of the same Southern California teens buying Ventures records were also among the thousands of surfing newcomers jamming the beaches between San Diego and Santa Barbara. They were screaming for Dick Dale almost before they’d even heard of him.

Dale was a teenage guitar ace in the mid-’50s when he moved with his family from Boston to a Southern California beach town, where he began surfing. He loved Duane Eddy’s thick echo-chambered guitar sound and the murderous chord progressions on Link Wray’s “Rumble.” But he also loved Nat King Cole, Hank Williams, and the Middle Eastern traditionals that his Lebanese-born father played. In the summer of 1961, Dale and his new backup band, the Del-Tones, played their first show at the Rendezvous Ballroom—a cavernous down-at-heels nightclub eight miles south of Huntington Pier. In better days, the Rendezvous had swung to the music of Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and Stan Kenton. But rock and roll, as far as city officials were concerned, was a public nuisance; two years earlier they’d shut the Rendezvous down altogether. Before Dale and band could play there, Dale’s father had to convince the club’s new owners, then city permit officials, that his son was going to put on a “musical review,” not a rock and roll concert, and that they’d enforce a dress code for all who attended.

Dale got a handful of his surfing buddies to show up at the Rendezvous, and handed out cheap ties from a cardboard box to anyone who came without the requisite neckwear. For the opening 15 minutes of his show, Dale played songs like “Begin the Beguine,” while his friends dutifully sat and watched. Then he shifted gears and did two or three country numbers, then some R&B covers, and finally launched into some rock—which got everybody on their feet, clapping and cheering.

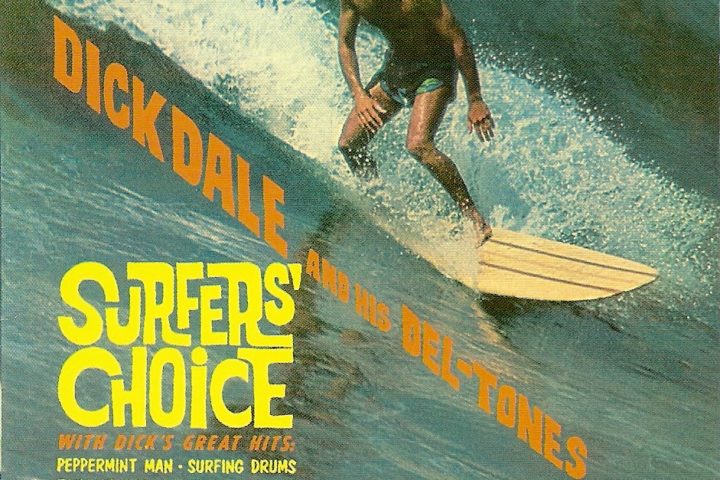

By fall, Dale’s shows at the Rendezvous were drawing crowds upwards of 4,000, and he had a regional hit with “Let’s Go Trippin’.” Fans began calling Dale’s instrumental songs “surf music,” and he ran with it. The front of his 1962 debut LP Surfers’ Choice showed Dale leaning into a neat little Hermosa Beach wave (the cover was shot and designed by John Severson), and the album’s song list included originals like “Surf Beat” and “Death of a Gremmie.”

Dale’s sound—surf music itself, for that matter—was best captured by a Greek folk song that Dale reworked for the Surfer’s Choice LP into a two-minute bolt of lightning called “Miserlou.” Dale’s technique, and that of his entire band, was pushed to the utmost. Same with his hardware.

Not long before recording Surfers’ Choice, Dale was introduced to guitar- and amp-maker Leo Fender, who gave Dale a Stratocaster guitar and asked him to stress-test his latest 30-watt amp and speaker set—which Dale promptly blew up. More testing followed. Dale liked to brag that he ruined nearly 50 of Fender’s amp-speaker sets, and that a few actually exploded into flames. Eventually, Fender came up with the 100-watt Fender Dual Showman amp and ran it through a fifteen-inch expanded-cabinet speaker; this sonic-monster combo later became the hardware cornerstone for metal rock.

Dale’s tough new sound hit American pop music’s soft underbelly like a balled fist. “Miserlou” begins with an ominous bit of single-note staccato guitar picking, and from there it’s a headlong minor-key musical car chase between guitar, piano, and trumpet. At various points in the song, Dale does a machine-gunning slide up the fretboard—his signature move—which he later explained was an attempt to re-create through music the feeling he got while dropping into a big wave. Later, other guitarists further defined the surf sound by turning up the reverb or by leaning heavily on the tremolo bar. But Dale himself, as he put it, was more into “just into chopping, chopping at the strings.” (Jimi Hendrix saw Dale perform at least once at the Rendezvous and became a huge admirer; the murmured line, “You’ll never hear surf music again,” near the end of Hendrix’ psychedelic instrumental “Third Stone from the Sun,” recorded in late 1966, is said to be his response to a false report that Dale had just died of cancer.)

Dale played all over Southern California, but continued making weekly appearances at the Rendezvous in 1962 and early 1963. Undercard acts in the surf-themed Battle of the Bands shows that Dale headlined included the Rhythm Rockers, the Pyramids (featuring Will Glover, surf music’s only black musician), and the Belairs, whose 1961 “Mr. Moto” single, released a few months before Dale’s “Let’s Go Trippin’,” is sometimes tagged as the first surf music single. Bands still performed in suits and ties, but male audience members all wore period surfwear: a white T-shirt beneath a slightly oversized Pendleton wool or Madras cotton long-sleeve, white Levis, and black Converse All-Stars or tire-tread huarache sandals. Packed tight inside the Rendezvous, teenagers invented the Surfer Stomp, dance history’s loudest and most rudimentary step—double-stomp right foot, double-stomp left foot, with enough force to send ripples across the hardwood floor.

Life magazine ran a short article on Dale in 1963, just as surf music was peaking, and he played “Miserlou” on the Ed Sullivan show. But he didn’t like to tour, and never sold many records outside of the West Coast. Other instrumental bands quickly filled the gap: the Chantays helped define the reverb-drenched “wet” guitar sound, and their song “Pipeline” reached number four on the charts, while the Surfaris hit number two with their drum-rolling low-fidelity masterpiece “Wipe Out.” Still, it was Dick Dale’s turf. Nobody batted an eye when he released a singled titled “King of the Surf Guitar.”

Instrumental surf music may have been inspired by the beach, but really it was a product of the garage—here was a bottom-up rock movement the likes of which wouldn’t be seen again until the birth of punk. And like punk, it peaked quickly. By the end of 1963, with old music industry pros jumping in with records like Bo Diddley’s “Surfers Love Call,” Duane Eddy’s “Your Baby’s Gone Surfin’,” and Preston Epps’ “Surfin’ Bongos,” the instrumental half of the surf music enterprise was nearly played out.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on Matt Warshaw’s excellent Encyclopedia of Surfing site. We liked it so much we asked if we could share it. Thanks Matt.