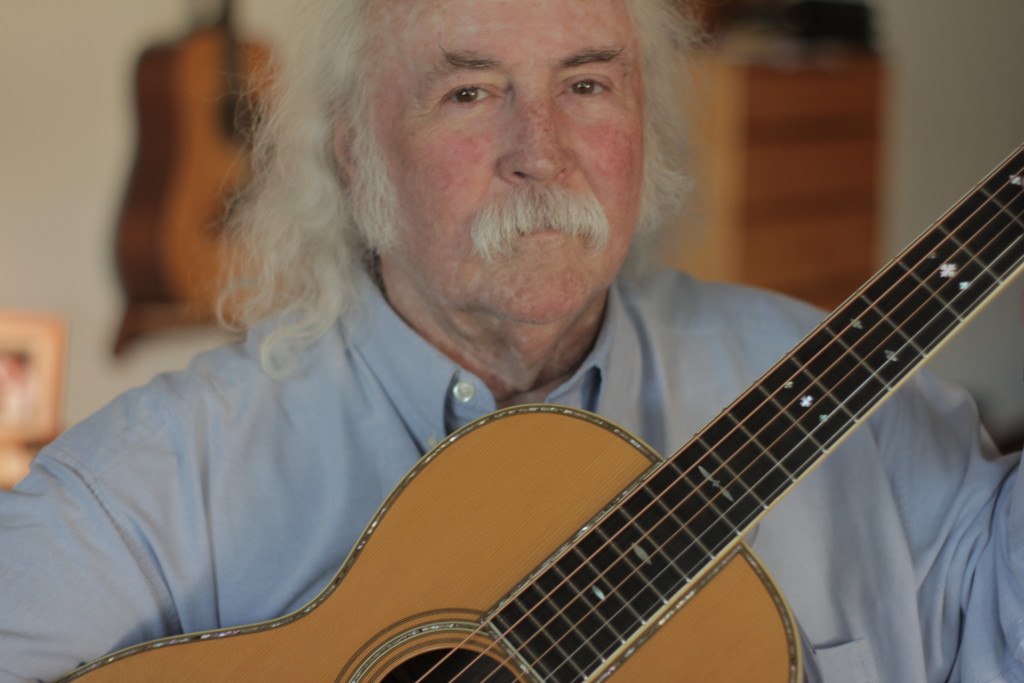

David Crosby is no different from a lot of us. He sports a Cheshire cat grin the minute he talks about guitars. He proudly explains how the Beatles changed his life and his love for music of all sorts, from folk to Steely Dan to the Fleet Foxes.

But of course, Crosby is no ordinary musician. Over his long career, he went from being an acoustic folkie to honing his electric chops with the Byrds to steering back to acoustics (with the electric sometimes thrown in) in various Crosby, Stills & Nash incarnations. He released the pivotal If I Could Only Remember My Name in 1971, the star-studded release that still sounds fresh to modern ears. And, obviously, he lived a hard life filled with drama, drugs and even a prison term.

Upon seeing him relaxing at his beautiful Southern California home, it’s hard to imagine the wild life that David Crosby once lived, not so long ago. His residence has to be in one of the country’s most peaceful places – Santa Barbara wine country. His home is quiet, warm and filled with mementos of a fascinating life, guitars he’s picked up along the way and—of course—his loving family.

On the day I interviewed Crosby, we talked for hours about the early folk scene he was a part of, shot some photos, filmed a video for fretboardjournal.com (a quick take on Joni Mitchell’s “For Free”) and then talked some more about guitars, music and life. Despite the roller coaster ride his body has been on, his voice is, quite simply, spine tingling. I asked him how it’s held up all these years. All he could say was, “I just don’t know, but believe me, I’m grateful.”

Fretboard Journal: What kind of background, musically, did you grow up with?

David Crosby: My parents played a lot of classical music in the house; I probably heard the Brandenburg concertos, you know, 289 times, by the time I was 6. But the very first 10-inch 33 LPs, we had several of those, and they were the Weavers, Josh White and a South African couple called Marais & Miranda. And soon thereafter, Pete Seeger on his own. And soon thereafter, Odetta. They were folk music. That’s what my mom bought. So that’s what I was raised on.

Then my brother turned me onto ’50s jazz. I never went through the Elvis period. My brother turned me on to to Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, that kind of thing. There was one radio act that punched through, which was the Everly Brothers.

Everly Brothers were a huge influence – huge – they just rang my bell. I loved their stuff. It was just too goddamn good. I loved harmony, right from the get-go.

FJ: Because of those Everly Brothers records?

DC: Largely. I loved it. And that affected how I heard folk music, when I started hearing folk music and groups, even ones as corny as the Limeliters. I liked the harmonies that they would do. And Peter, Paul & Mary were good: they weren’t corny, they were good. And then you start hearing the words that people were delivering.

FJ: I know you made your way to Greenwich Village and hooked up with Fred Neil. What influence did he have on you?

DC: First place, he had a very deep voice, very beautiful one. Second, he would write songs…good songs.

FJ: Was Fred Neil someone you were aware of before you moved out to Greenwich Village?

DC: I got to New York. I was a folk singer, playing in little coffee houses. And I ran into three people: Fred Neil, Vince Martin and a woman named Lisa Kindrid. They were all singing in the same coffee houses. And Bob Gibson, a really good 12-string player.

Freddy just had more on the ball than anybody else; he could really sing and he was a very soulful cat. And he was mesmerizing: he was extremely good. All of us kids that were wanting to be folk singers were taken by him. I don’t think that anybody that I knew that had heard him wasn’t very, very strongly influenced by him. And then he went down to Florida where Vince was from. They made one record together, the two of them, and they both went back down to Florida. I got a message from either Fred or from Lisa – I think it was Fred – saying, “Hey, there’s work down here. There are coffee houses. If you come down here, you could eat.”

And this was, you know, very tough times early on. We were playing basket houses, which were places where you pass the basket afterwards. So I took two cardboard boxes and my Vega 12-string and I went down to Florida and started singing down there, and became very close friends with a guy named Bobby Ingram, who was and still is a musician down there, a good one. We both learned a great deal from hanging out with Freddy.

Freddy would do things to your head. We would be in an elevator in New York in an old, crapped-out building in New York, and he would turn off the light. He would say, “Listen. The music’s everywhere.” And you’d hear, tang, tang, tang, ding, ding, ding. We’d get stoned and we’d be sitting next to a bamboo thicket, and he’d say, “Listen, that’s music.” It was a bamboo thicket in the wind, but it was beautiful. He was a pretty amazing guy.

FJ: How much older than you was he?

DC: I was maybe 20, and he was probably 50. He had a very strong influence on me, probably stronger than Gibson, stronger than most people at that time. And when I was in New York, I had run into Dylan. He was a strong influence.

Up till that time, the only people who had ever even made a record in folk music were Peter, Paul & Mary.

So I went over to Gerde’s Folk City and I’d listen to Dylan. I thought, “Well, fuck, I can sing better than that .” Then I started listening to him at work and I thought, “Oh, shit.” Then I had to start rethinking what I was going to be able to write.

But they made me fall in love with acoustic guitars and they made me fall in love with singing…all of those guys did. Him and Baez. As soon as I ran into Baez, I, of course, like everybody else, fell in love with her. She was a good picker. She still is.

And I have been in love with acoustic guitars ever since then. My brother gave me my first one, I don’t even know what it was, it was some kind of nylon-strung thing. I learned E-minor to A-major and sat there playing “Follow the Drinking Gourd.”

FJ: You and Travis Edmonson of Bud & Travis played together, right?

DC: Played together, no. I used to sit and watch Travis. Endlessly. There was a club in Hollywood called the Unicorn. It was just a dive and he would play there. It was a “coffee house.” I would just sit there and hawk his changes and try to figure out what he was doing. He was more accessible than most of the rest of the guys. He would show you, he was friendly. And gave me my first joint. I learned a bunch from him.

FJ: What was that first 12-string you heard?

DC: Bob Gibson’s. Freddy had one, too.

FJ: You just knew you wanted one, immediately?

DC: Yeah. I mean, listen to the damn thing. It’s like a piano. This one [holding his original D-18 that he had converted to a 12-string] in particular. I think this is probably the best acoustic one I’ve ever heard. I tried to copy it a number of times. Santa Cruz made me a copy of it. Martin made me a David Crosby model 12-string that’s a 12-fret like this.

I sent Martin this guitar, and they said, “Somebody very amateurishly shaved the braces in here. That wouldn’t have been you, would it?” And I said, “Uh, yeah.”

FJ: You did?

DC: Yeah. I shaved the braces a little bit with a Coke bottle and some sandpaper.

FJ: When was that?

DC: That was when I first got it. When I bought it, I was in Chicago. I rode a bus out to the only store in Chicago that had a D-18, which was all I could afford from Martin. I got it and I wanted it to be loud. And even though this was late ’50s or early ’60s, you can make ’em louder. They were building ’em lighter then than they do now.

Now they’re building them to try and last 50 years. Which is admirable on their part, on the one hand, and yet, on the other hand, those guitars don’t ring anywhere near. When they made the David Crosby D-18, I said, “Build it light.” I said, “Do not build it to the kind of specs you have been building, where you expect a guitar to last 50 years.” And so those David Crosby D-18s ring like a bell, because they’re built lighter and braced lighter.

FJ: How long was it a six-string before it got converted?

DC: Several years. I was playing it when we started the Byrds. Dylan offered me a grand for it one time. Stephen [Stills] offered me an old Bentley for it. And this is back when $1,000 was $1,000. A lot of people have wanted it, because it’s a really good-sounding 12-string.

FJ: At one point, you joined Les Baxter’s Balladers, right?

DC: I was in there and so was my brother. He was playing bass, and myself and Bob Ingram, and another guy named Mike Clough, and it was really pretty pathetic. It was an imitation Christy Minstrels, if you can imagine such a thing. That’s really pretty far down the line.

FJ: Straight out of A Mighty Wind?

DC: Well, we needed money. We were trying to live. We needed to have some money for food. And they dressed us up in little pegged pants – black pants – and little red bellboy jackets. It was pathetic. But we were good, we could sing. We were on tour, in Baltimore, when Kennedy got shot.

I hated being dressed up like a monkey. They were trying to make us be a lounge act. And that was a horror show for us, because we were folkies and we wanted to be like Bob Dylan. We listened to Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie and the Weavers. That’s where we came from. And that had nothing to do with bellboy jackets.

Josh White and Odetta had given us our standard that we were reaching for. That’s what we were trying to do. We wanted to be as good as those people.

FJ: When you returned to California, you were doing that whole Ash Grove and Troubadour circuit. Were you a solo act? What were you singing?

DC: Some really cornball stuff, like “They Call the Wind Mariah.” And the occasional good song, a really odd hodge-podge of stuff.

Then I started writing my own. Not any good, but I started writing my own songs. And you’d get up at the Hoot Night at the Troubadour. As much as anything else, we were trying to attract the attention of girls.

FJ: This was you solo?

DC: Yeah. I worked for a while with my brother. Once I had established myself down in Florida, I told my brother, “Come on down,” and he would play bass with me and sing harmony. And that was fun for a while. We wound up in Omaha someplace and we kind of split up. And then I went to Chicago from there.

Chicago was where I encountered the Beatles. That pretty much changed everything.

FJ: What was it about them?

DC: It changed my outlook on what I wanted to play. You’ve got to remember, there was a big synthesis going on there; up to that point, now, rock ’n’ roll had been pretty much four chords – almost entirely, as a matter of fact. That was the standard thing that came out of the Brill Building, but it all had a backbeat. Well, here were these guys from England, they were playing folk music changes, much more complex chord changes – much better musically, but with that backbeat. That was a mixing of two streams that created a new thing.

And it was irresistible. I went from Chicago to L.A. I walked into the Troubadour and there was Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark singing that kind of stuff. It was Gene Clark who didn’t know any of the rules at all; he just started writing whatever sounded like the Beatles.

And Roger’s one of the major talents of our times. He was a more advanced musician; he’d come out of Chicago’s Old Town School of Folk Music. And he really knew how to play, in particular a 12-string. He started playing those Gene Clark songs and that just pulled me like a magnet. So I started sitting around with the band and singing harmony. And that worked, that was fun.

FJ: When did you really ramp up your songwriting?

DC: When there was a venue for it: when the Byrds started to actually be a band; when we got Chris Hillman to come and play bass for us. He was a mandolin player in a little bluegrass group. But he was fascinated by the music and he learned how to play bass to be in the Byrds. He had never played bass before.

Michael Clarke had never played trap drums before in his life; he played a conga drum. He was somebody that I met hitchhiking in Big Sur. I said, “Come on down to L.A., man. You look right. You should be in a band.”

FJ: That was all it took, the look?

DC: Yeah. And he learned how. And none of us were very good, except Roger. Roger was really good. He could really actually play. Then it turned out he had this other talent, which was to be able to arrange – to translate – from a folk idiom into this early rock ’n’ roll stuff that the Byrds did. He could arrange the song so that it would change it; he took “Mr. Tambourine Man” and made a record out of it – made it completely different than how Bob wrote it, hugely different from the demo that we heard, which was Bob and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott just out of their minds.

FJ: What was the demo like? The two of them alternating lines?

DC: No, Bob was singing the song and doing something that he still loves to do, which is to sing the song and get somebody else to sing along who doesn’t know the song. And it was pretty terrible, but you could hear the song if you listened to Bob.

FJ: How did you end up releasing that before Dylan did?

DC: I introduced those guys to a record producer who was around Hollywood at the time, named Jim Dickson. Jim knew enough people to get us into a jazz recording studio down on Third Street [World Pacific Studios]. He would get us in there after they finished their sessions for the day. So some nights we started at 11:00, and some nights we started at 7:30, and some nights we started at 1:00, but we would get in there and it was a place to play. He could also record us.

The trick about that was that we had to listen to it back, and that was brutal.

FJ: That’ll get your harmonies in line!

DC: Yeah, it was brutal. It short-circuited the garage band phase of the Byrds by years, because if you’re just playing in a garage band, you think you sound terrific. There’s nobody there to tell you that you don’t. Your girlfriend says, “Wow, that was really cool, man.” And there’s nobody there to say, “Yeah, it was really cool, except it was all completely out of tune, and you turned the one around to the backbeat, and that’s not the root of that chord, and…” We were confronted with that right after we had just played it.

FJ: Did the studio owners ever know that this was going on at night? Did they care?

DC: I assume they did, and I don’t think they gave a shit. As long as we locked the place up when we left.

It started, after a while, to sound better, and then Dickson knew the guy who was managing Bob. Bob came, listened to “Mr. Tambourine Man,” and said, “Oh, man.” You could see it click in his head: he knew right then what he was going to do. He knew what was going to happen. He went out and found the Band and started playing electric music, because he knew at that moment that his stuff could be played that way. And he liked it.

I wish I could take credit for it– I could take credit for some of the harmonies – but the credit goes to McGuinn. He really saw how to do it, and we went out and bought exact same axes that the Beatles had. I had a Gretsch Tennessean and McGuinn had a Rickenbacker 12-string. The only difference was we used a Fender bass…better.

FJ: Where was guitar shopping in those days in Los Angeles?

DC: Wallich’s Music City, right at the corner of Sunset and Vine. I still have a Gibson 335 that I bought at Wallich’s Music City brand new.

I went through two Gretsches. I had a Gretsch Tennessean that I started off with. You would have died laughing if you could have seen me in front of a mirror… I had no idea how to play an electric guitar. Didn’t know how to hold it, how short should the strap be. It was hysterically funny, now that I think back.

I was doing really silly things like that. I would play electric guitar while wearing this cape.

FJ: When you moved away from the Gretsch, were you just seeking a different tone?

DC: I started out with that Tennessean because that’s what George [Harrison] was playing. And then I saw a Country Gentleman. I thought that looked so cool. And I had to have a Country Gentleman. I played that for quite a while.

The thing that Gretsches have got is that if you roll the volume all the way on and then control the volume during the set from the amp, there’s a certain crunch that they’ve got on the bottom that’s really wonderful. So I did that for a long time, but then I saw that 335 hanging on the wall at Wallich’s Music City and I thought, gee, that’s a pretty fancy-looking guitar. I confess to being somewhat taken with guitars.

FJ: Guitars, planes and boats, right?

DC: Well, particularly guitars and boats. Guitars and boats have remarkable similarities. They’re both made out of wood. They’re both under tension from wire. They’re both evolved shapes, not invented shapes. they’re both exquisitely beautiful. They both faintly resemble women. And they both transcend the state in the universe of a thing, normally, because they do something. A thing, an object that you make, has an innate value built into it, depending on what it was made to do. A fencepost doesn’t have a lot of innate value. But a guitar, a guitar can take over your whole life. It can make people cry. It can make people laugh. It can make people feel elevated. It’s a thing that — and it goes way beyond thingness. And a sailboat does that, too.

FJ: You’ve really embraced modern guitar makers like Roy McAlister and Kevin Ryan. Do you have the same appreciation for modern sailboats?

DC: No. Modern sailboats are made of fiberglass. And fiberglass sucks!

FJ: You’re known for playing in alternate tunings. When did that come about?

DC: The alternative tunings thing…how that happens is you’re sitting there with a regular guitar and you play a D chord. But that E is on the bottom, right? And that is always in your way. And the A is not the root, so you’re really limited to that, until somebody shows you that you can take that bottom E down to D, and then all of a sudden you got that great sounding chord. Well, that’s the beginning of a long, slippery slope.

I started messing around with tunings somewhere towards the end of the Byrds. And if you sit there long enough, you eventually start playing stuff that doesn’t come out of regular tunings.

FJ: Are you writing your lyrics like poetry first, and then writing the music for them? Or does it go both ways?

DC: I think with “Guinevere,” I think it happened pretty much the same time.

FJ: So was “Guinevere” a byproduct of you stumbling upon the tuning and then it just coming out? That’s amazing.

DC: Yeah, well, years later, one of the guys in the Grateful Dead pounded this for me and said, “You know what you’re doing?” He said, “Two, three, five, six, seven – one, two, three, five, six, seven – two, three, five, six, seven.” And I thought, “Uh-oh, really?”

Nobody owns any of ’em: they aren’t mine, they’re – Joni’s aren’t Joni’s. Anybody can tune a guitar in any way they want and you make up new chords. Probably the greatest person at doing that of all was Michael Hedges. Although I’d say Joni wasn’t far behind. Joni was far ahead of me.

FJ: So, there’s a rumor about the end of your stint in the Byrds… did it have anything to do with you trying to get them to play “Triad”?

DC: I don’t know how much that had to do with it at all, truthfully. I think at the time we were young guys who had been butting heads with each other. I was growing very fast. I wanted a bigger piece of the pie. I was writing good songs. In those original groups, you were expected to stay in the role – the rhythm guitar player or harmony singer – and stay there. And that didn’t work really well for Chris, either. He was supposed to be the bass player – the young-looking, really nice bass player. He wasn’t supposed to sing and play and write songs and stuff. And all of the sudden here comes Chris, and he’s a real talent, and he can write and he can play and he can sing. And if you’ve heard him with Herb Pedersen, you know damn well he can really sing and really write and really play.

Well, we didn’t fit into the roles anymore. We all had egos and we had other people stirring the pot from outside – bad managers and stuff. And, you know, I was certainly not an easy case to get along with. And they threw me out of the band and said they would do better without me, which didn’t work out for them, because about six months later, we had Crosby, Stills & Nash at No. 1.

FJ: Was that really the amount of time between groups?

DC: Pretty much. Maybe a year. It certainly wasn’t longer than a year. And, since then, you know, I have gone back to Roger many times. Now Chris and I are friends.

FJ: So, with CS&N, was the process similar to the Byrds? Going into a studio to work on tunes and listening back the whole time?

DC: Completely different process. You’ve got to remember, by the time we’d got to CS&N, we’d already done the Byrds, the Hollies and the Buffalo Springfield. We knew. We were now veterans and we knew how to make a record. We knew quite well how to make a record; we had already made hit records. Nash had made more than Stephen and I put together, but we all knew how and we had songs. We could sing you the entire first album, the couch album, anytime, anywhere…just sit down and sing it to you, the whole record.

We wanted to be on Apple records, so we went to London for a while. And finally, one day, we got George and Peter Asher to come over, and we sang them the record. And they said, “Well that’s nice. That’s nice. It’s very good.” We left and we got a phone call a little bit later saying, “I don’t think it’s quite what we want.” And I am willing to bet that they regretted that decision more than any other one they made. I’m friends with Peter now. I still haven’t asked him. But I think they probably regretted that, because we went back and Ahmet Ertegun was totally thrilled with it, very eager to put it out. And in the year of the guitar player, when everybody else was Clapton and Hendrix, we just came out and killed it.

FJ: The chemistry between the three of you must have taken a little bit of time for it to jell, or was it just natural from the get-go?

DC: I had dug Steven’s playing and singing when he was in Springfield. I thought, “Geez, that kid is really talented.” He had a really great sense of time and a lot of ego, but it was kind of justifiable. He really could do it. When Springfield came apart, he and I were hanging out together singing songs and goofing off. Cass Elliot was a dear friend. She’s the one who introduced me to Graham. She put him in my path and I brought him to Stephen. We were at Joni Mitchell’s house, whom I had been going with and had brought out and produced her first record. And then she started going with Graham, which I really didn’t blame her for. Graham was certainly the most polished one of the bunch!

Stephen and I had just met him and we sang one of Stephen’s songs to him. He said, “Would you do that again?” And we said, “Sure.” And we did it again. It was “In the Morning When You Rise.” He said, “One more time.” And Stills and I said, “Why should we sing it three times?” And he said, “Please. Just for me. Sing it three times.” And the third time we sang it, he put the harmony on the top and both of us looked at each other and went, “Oh, shit!” And that was pretty much that.

The only thing we wanted to do was get into a recording studio and do that, because we all had songs. I had written “Guinevere” by that time. Nash had “Marrakesh Express” and another song called “Right Between the Eyes” – good songs –and “Lady of the Island,” stuff that really didn’t fit the Hollies. He’d outgrown the Hollies. And Stills was in the process of writing “Judy Blue Eyes” and had “Helplessly Hoping” and “In the Morning When You Rise,” and things like that. It was just as natural as a thing could be. We got some money from Ahmet and went into the studio and made that record. It didn’t even take long.

FJ: Were you playing much on that first record or mostly singing?

DC: I played on the things that I could play. Nobody else but me could have played “Guinevere.” And I played on “Long Time Gone” and “Wooden Ships” – the other things that I wrote.

FJ: What instrument did you use for all those?

DC: D-45s, a D-18, D-28s and that Martin 12-string.

FJ: Your solo record, If I Could Only Remember My Name, was groundbreaking. If that was released last week it would be played on college radio stations alongside indie rock bands.

DC: I think it was a little too far ahead of its time. You probably don’t know this, but Rolling Stone, when they reviewed it, they said it was “mediocre.” That’s the word they used. And I think it’s ’cause they didn’t understand it and because it wasn’t like anything else that had come out. But still, to this day, a lot of people like it.

FJ: Do you like it?

DC: I love it.

FJ: And there are all these additional clips floating around on the Internet of the Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra.

DC: That’s something [Jefferson Airplane’s Paul] Kantner came up with. Here’s how it actually happened. There never really was a Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra. What happened was in the middle of us making Deja Vu in San Francisco, the girl that I was in love with got killed in a car wreck, and it pretty much destroyed me. I did not have anywhere near the equipment to deal with that.

I had no experience, nothing, didn’t know how to cope with that at all. So I did two things, one good, one bad. The good thing was I kept going to the studio because it was the only place I felt safe. It’s the only place I knew what to do with myself. And the other thing is I started doing a lot of hard drugs, which was very bad, and, as you know, nearly destroyed me. But at that point, the studio thing was still working really well. So I made If I Could Only Remember My Name. In doing so, I just told my friends, “Come on down. I’m going to be there every night. It’s where I go. It’s what I do.” I had the money to just keep the room.

Deja Vu was selling faster than they could print it. Some of those guys [at the session] were truly my friends: Nash still is truly my friend. And [Jerry] Garcia used to come almost every night. And we would fool around. Phil Lesh. Jack Cassidy came a lot. Jorma Kaukonen came a lot. These were all guys that I’d been friends with for a long time – Kantner, Grace [Slick] – these were all good friends and good people and they knew that I was lonely and they knew also that I was slightly nuts at the time, and they would come and we would play music. I had songs. I’d only used two or three of my songs on Deja Vu, so I had a lot. I would sit down with whoever did show up – most often Jerry – and start playing a song.

Music was honey to flies to him. If you started playing music, he wanted to play. And we had two-track tape running constantly the entire night. And the minute that something started to happen, the 24-track would start to roll – or maybe it was 12 track back then. I don’t know. It was rolling. And then I would start layering harmonies onto it, and that was a lot of fun and I’m good at it and I just had a blast with it. I’d sing a lot of nonparallel things. And it wound up being really a delight. Now there are a couple moments in there that are transcendent. I’d obviously listened to too much Bach. But the thing at the end –”I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here” – I really don’t know what you call that. It’s certainly not something anybody else has ever done.

And it’s just me fooling around with that echo chamber. “What Are Their Names”…that one was a jam.

FJ: Given that it was like that and that you had the tape rolling all the time, how did you know when to stop? How did you know when the album was done?

DC: I didn’t. And that’s when the P.E.R.R.O. part came in, because we were continuing to fool around with “The Mountain Song” and there were a number of other pieces of music that we were hoping to develop into something. And it’s not like Jerry didn’t have a lot of music, too. But once we had that album, once it started to take form, then I finally just checked out of the room, and that was the end of that. But in the meantime, there were a lot of tapes that were attempts at this and attempts at that and almosts of this and almosts of that. Paul was getting unhappy with Jefferson Airplane, so he started calling it Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra. And I think he hoped that there actually would be a Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra. But it lived in his mind. And once I had that record put together, I had just put it out. Then the next thing that I did was start working with Nash on the first of now many Crosby & Nash albums.

FJ: The year that the solo album came out, Four Way Street came out too, right? It was a crazy year. Was that right?

DC: Four Way Street was a hair later. Roughly around the same… I didn’t have a lot to do with Four Way Street. I just sang some stuff on it and let them put it together.

FJ: You and Nash go so far back. Do you guys talk every day?

DC: Mostly. He’s a good man and he’s sort of a renaissance man. He’s a guy who came out of one of the toughest, grittiest industrial cities in all of northern Europe, Manchester, who said to himself, “You know, I don’t know about anyone else, but I am not going to wind up working in that factory. That’s not it. I’m going to play my way out of here.” And he did. Now look at what he’s made of himself. He’s a world-class authority on photography and art. He knows more about the early stages of photography than almost anyone I know. He broke into digital printing of photography so early and so far and so deeply that his printer is now in the Smithsonian. This is a guy who seriously affected how you make photographs. And he’s a good human being.

FJ: And you’re about to go to Europe together?

DC: Going to Europe with Nash. Big, big fun. Of all the different entities – CSN&Y, CS&N, Crosby Nash – I think Crosby Nash is probably the most fun.

We look at things very similarly. And he’s a generous man. He gives to the music pretty wholeheartedly and he’s not competitive. There’s two kinds of ways to approach music and one is to give to it and try and create something where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts…where magic happens. And the other is to try to impress and also particularly aggrandize yourself. And Nash is the first guy. He’s a joy.

FJ: Do you talk to Neil Young much?

DC: I talk to Neil fairly often actually. I call him up and talk to him. We go back and forth about, “Well, you shouldn’t have done this,” or, “You shouldn’t have done that.” All of us do. The four of us do. There’s never been a time when some of us haven’t been happy about someone else’s choice about one thing or another.

FJ: And you still talk to Stills regularly?

DC: All the time. I like Stephen. I’ve got to tell you, two nights ago at the Beacon [Theater in New York], Stills was just terrific. Everything you could ask of him, he delivered. He was really good.

FJ: Who do you talk about guitars with the most?

DC: I talk guitars with Jackson [Browne]. I talk guitars a lot with a young guitar player named Marcus Eaton. He’s a guitar nut and an incredible player. I talk guitars with James [Taylor]. I talk guitars with a lot of people, truthfully.

Nash, of course, was much smarter than I was about buying guitars. I bought guitars that sound great. I would hear a guitar and think, “Oh my god, that thing sounds like a bell,” and buy it. Nash would go out and, well, last night on stage he was playing Duane Allman’s guitar!

FJ: He took the collectability into account?

DC: Yeah, he’s got Johnny Cash’s guitar, he’s got Duane’s guitar. He’s got guitars, with a capital G.

FJ: I see that you own guitars by luthiers Roy McAlister, James Olson and Kevin Ryan. Are there any other builders you admire?

DC: Martin. When it all comes back down to it, you have to go back to Martin and look at them and say what a phenomenon they are. Because to this day, Martin guitars will build you, can build you and does build you, every day, a guitar that you just can’t believe.

Admittedly, it comes off an assembly line. But the guys on that assembly line are the best guys in the world. There are only a handful of guys who can equal them.

FJ: What guitar are you most bummed you sold?

DC: A 1939 Herringbone that I had that I traded for drugs. I’ll regret that the rest of my life.

FJ: Do you know where it ended up?

DC: No. These things happen, man. You make mistakes in life.

This article originally appeared in the Fretboard Journal #25. Crosby fans should also listen to Fretboard Journal Podcast Episode 92, where singer-songwriter/producer Joe Henry interviews David Crosby at the Fretboard Summit.