The first time Jean Larrivée stepped onto an airplane, he was 33 years old. The wood savant was so — pardon the expression — petrified of airplanes, he would often have nightmares about them. But when Larrivée was invited to host a guitar–building clinic in rural Saskatoon, he simply could not refuse.

That inaugural flight, from British Columbia to Saskatchewan, wasn’t exactly an antidote to aero-phobia. In fact, he says, it was the worst flight he’s ever taken. The horrible puddle-jumping journey, bumpy all the way, ended with the pilot missing the runway; his return trip, on a plane left over from his grandfather’s era, wasn’t much better. But he’d made it home, safe and sound, after delighting the more than 100 clinic attendees who’d gathered from across the province to learn from this master Canadian luthier.

Before too long, Larrivée was on another plane. This time, however, he was bound for wood — some noteworthy North American stash of spruce or cluster of cedar. Then it was on to Europe and, eventually, Asia. Air travel, once so utterly terrifying to him, had become an integral component of his job as a guitar builder.

For the last three decades, Jean Larrivée has been traveling the world in search of the finest wood for his guitars, often at his own personal risk; he is on the road for as many as five or six months a year. Yet, a multitalented, fanatical craftsman, he is still able to get his hands on, at one stage or another, pretty much every instrument to come through his spacious Oxnard, California, shop. He may start his week carving necks and joining tops and end it watching elephants drag prized rosewood logs, felled by a recent monsoon, out of the Indian jungle.

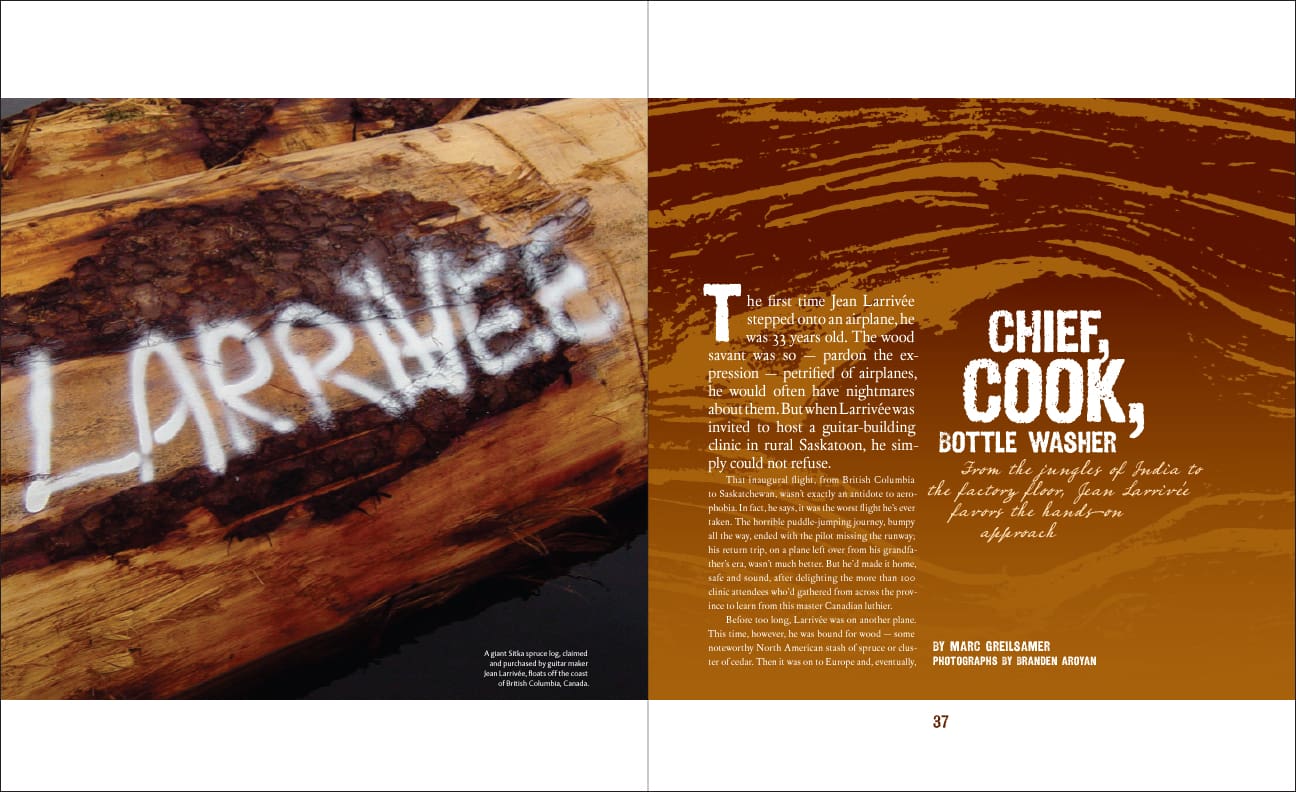

Based in California since 2001, Larrivée is ready to hop on a plane to, say, Vancouver at a moment’s notice — if he gets tipped off about “some good logs” floating in the northern Pacific. He visits Hawaii, Europe, China and India multiple times per year, and while his fear of flying may have abated, his adventures continue.

On a recent trip to India, Larrivée flew from Mumbai to the small port city of Kochi, in southwestern India on the Arabian Sea. (Thanks to a public workers’ strike, the garbage level in Kochi was rather high.) He then traveled for hours and hours over flooded roads into the jungle to select logs and visit sawmills. (Since rosewood is protected, Indian wood suppliers wait for monsoon winds to do the dirty work, then haul the fallen logs into depots for auction.) Larrivée had made the journey in order to illuminate suppliers and mill workers as to his demanding quality requirements regarding grain, color, cut, etc. The most traumatic part of the trek, however, was back in Mumbai.

“I get off the plane [in Mumbai], and I’m a little wired,” he remembers. “I go through customs, and everything is funneled into an area, and the next thing you know, I’m out in the streets and I can’t get back in.” With his flight to Kochi a mere six hours away, he’d planned to spend his layover in the comfort of Chhatrapati Shivaji International; now he was locked out of the airport, which had closed its doors for the night. Despite being an experienced and knowledgeable traveler, Larrivée was not comfortable spending his next (last?) few hours on the streets around Mumbai’s airport.

“You talk about poverty,” he says. “I’m trained for this, I’m good with it, but there, you’re not. It’s not a safe place, it’s very dangerous.” A cabbie offered to find him a room on short notice, but after his first choice was booked, he ushered Larrivée to, well, his second choice.

“You wouldn’t dare take your clothes off or open your suitcase,” he explains. “Forget it, you wouldn’t do that. I wouldn’t even open my computer. So I left everything untouched; never even took a toothbrush out. It was just that bad. Cockroaches flying all over the place, the floors are all ripped up, the walls are all peeling, no locks on the door, and finally I just laid there . . .

“What an experience that was. It’s something I would never want to experience again. It’s funny, on one hand I love talking about it, but while it was happening, it was not fun.”

Was it worth it?

“I knew why I was going and what I was getting,” Larrivée says of his rosewood reserve. “I just had to go select it, and there was a lot of it. So I got a lot and I’m going back in three weeks.

“And I’ll buy an ocean of it again.”

Ask Larrivée how much one of his guitars costs, and he couldn’t tell you. (“I don’t know anything about money,” he declares. “I wouldn’t have a clue in the world.”) Everything else about a Larrivée instrument, however, will be second nature.

“I’ve worked with those guitars now 40 years,” he says. “I understand them so well. I can tell how good it’s going to be without even plucking the strings — just by looking at the guitar and looking at the wood.” Perhaps the business end of things is best left to others.

“He focuses on guitars — that’s what he does,” says his son Matthew, general manager of the Oxnard shop. “He worries about finding wood, but he doesn’t worry about whether sales are good, sales are bad or what the market condition is like. He really is devoted to the instrument itself, and he has this great ability to put blinders on and run with it.”

Jean Larrivée claims that he himself has selected every grain of wood in the shop. (“I don’t buy wood unless I see it,” he asserts. “I have a policy.”) If he goes to India to buy 5,000 sets of rosewood, he will go through it piece by piece, down to every bridge plate.

“I don’t think anybody out there has ever been exposed to as much wood as I have,” Larrivée states. “Once you know the characteristic of a certain color of wood — like Indian rosewood — I know the ones that sound good. And spruce, I can spot a good top from 10 feet away.

“That’s why I’m the buyer.”

It’s early autumnin Oxnard, California, which means, of course, that it’s berry-planting time. Boasting some of the world’s most fertile soil and a mild Mediterranean-style subtropical climate, Oxnard is an agricultural hub, famous for strawberries as well as sugar beets and lima beans. Oxnard is also home to the only deepwater port between San Francisco and Los Angeles, making it an axis for international trade, and especially since World War II, it has become a center for the defense and manufacturing industries as well.

Driving through this city of 200,000, one can’t help but notice the peculiar mix of farmlands, factories and industrial parks. Foothills lie in the distance, the occasional palm tree sprouts; seemingly endless rows of crops give way to clusters of nondescript office buildings and warehouses.

Tucked anonymously amid the shippers and distributors in an unexceptional Oxnard industrial park is Larrivée’s 16,000-sq. ft. American factory, which opened in September of 2001, just days before the terrorist attacks that would, among other things, shatter the American economy. (The company still operates its 33,000-sq. ft. facility in Vancouver.) “I built everything you see here,” says Jean Larrivée, and it’s obvious he means that quite literally — every light bulb and vent, every tool and machine, every shelf and worktable. He has also trained pretty much everyone on the shop floor, which, in Oxnard, amounts to 50 strong.

Apparently, Larrivée had long harbored dreams of a life in California — and its weather. “He always has,” says his son Matthew. “I know it, and I’ve known it for a long time. . . . It’s a quality-of-life thing.” (With a temperature range of 50 to 75 degrees and about 350 days of sunshine per year, that’s quality.) Turns out the dry, temperate climate that is so pleasant to live in and so conducive to growing strawberries is also quite favorable for storing wood and building acoustic guitars. Still, even Jean Larrivée admits that the move to Southern California was as much “for my own personal self” as it was for the health of his business.

Sunny, seaside Oxnard seems a world away from Montreal, where Larrivée was born on D-Day, June 6, 1944. He grew up outside of Montreal in an eastern Quebec township that he says “doesn’t exist” anymore. (“You don’t want to know this word,” he says mysteriously. “It’s Montreal, for all intents and purposes.”) The second oldest of four brothers and sisters in a French Canadian family, Larrivée considers himself to be “the last of the real French generation” and says he is the only one in his family that still speaks French. (Each of the siblings, including Jean, married English-speakers.)

Larrivée’s father, Henri, was a cabinetmaker, and so Larrivée was exposed to woodworking at an early age. “That’s where I get some of my skills,” Larrivée notes. “Just by being the son of a cabinetmaker, you sort of inherit that stuff.” Larrivée’s mother, Blanche, died when Jean was very young, and so rather than fin-ish school and apprentice with his father, Larrivée was forced to go to work.

“As a young man, I had to work as a lumberjack, you know, with horses,” he remembers. “I was pulling logs out of the forest, and that’s where I get a lot of my skill with wood. I have no formal education, but what I do have is a very good knowledge of wood, and that’s why I’ve always been successful with logs.”

Larrivée’s formal education ended after eighth grade; he was, by his own account, a “street kid.” “I don’t mean like a street kid breaking things and stuff,” he clarifies. “I lived in the street. It was hard to get me in the house, you know? I just liked being in the street.”

His early experiences on the street — “playing and learning life,” he says — helped him develop a sort of kinship with “regular” folks around the world. “One of the reasons why I can travel so well,” he explains, “is because I grew up in the street. I can go anywhere — and let me tell you, some of the places I go, you wouldn’t want to go there — but [it’s] because of the way I am, because of my early background. “I was always fascinated by slums,” he adds. “I don’t know why. Today’s slums and yesterday’s slums are not the same, OK? Today’s slums are full of drugs, and in the old days, it wasn’t like that. There were just old people, who didn’t have any money, and they tried to survive.”

Clearly, Larrivée’s childhood dramatically shaped his worldview. “Everybody that knows me will tell you that wealth does not impress me in any shape, way or form,” he announces. “To be my friend, you don’t need to have money. I’m fascinated by people that have certain talents. Money doesn’t excite me, and probably [my childhood] has a lot to do with it.”

As a boy, Larrivée delighted in the sounds of country stars like Eddy Arnold and Nova Scotia-born Hank Snow; when he was a little older, he relished the guitar licks of Chet Atkins and especially Duane Eddy. Despite his attraction to wood — and music — Larrivée’s young, inquisitive mind moved in other directions.

He apprenticed as an electrician for a while, but he hated it. (“I used to get shocks,” he laughs, although the electrical knowledge he gathered during this period became quite useful when building his own factories.) Larrivée decided to pursue a job in the automotive industry instead, and left Montreal for Toronto when he was 17 to become a mechanic. He was becoming “very Anglicized,” he says, and felt Toronto would be best suited to his vocational aspirations.

Once in Toronto, he went through all stages of apprenticeship, became a licensed mechanic and eventually landed a job with General Motors. (According to legend, he had the highest score in the province on his mechanic’s license exam.) “I could rip things apart real fast, and I could put them together real fast,” he says of his auto-mechanic days. Then, in 1967, he stumbled into a new career.

In hindsight, guitar building seems an obvious choice for Jean Larrivée, but his introduction to lutherie came about by mere happenstance. “It was an accident,” he says. The initial spark came thousands of miles from Toronto.

“My passion [for guitars] started on the beach in Vancouver,” he recalls. “I was living in Vancouver for a short time, also working as a mechanic, because I had decided to leave [eastern] Canada, and I met this guy. I couldn’t believe the style of guitar that he was playing, which was really sort of Chet Atkins-style on a classic guitar — completely different than what I had been teaching myself. I was teaching myself Duane Eddy stuff and that kind of thing, right? I said, ‘Who’s your teacher? My God, I gotta learn from this guy.’ ”

The teacher in question was a Vancouverite named Bob Neveu, but Neveu had moved to Toronto. “The next thing you know,” Larrivée says, “I’m off to Toronto. I moved a couple blocks away from him, and he was my teacher for several years.” Larrivée learned a great deal about playing from Neveu, but at this point, he still wasn’t building. It was through Neveu, however, that Larrivée got an opportunity to meet the legendary German classical-guitar builder Edgar Mönch (see sidebar).

Neveu and Larrivée had been invited to a student recital, which included a performance by Mönch’s talented 14-year-old son, Eddie. Larrivée met the elder Mönch at a post-concert reception, and after chatting awhile, mostly in French, Mönch invited Larrivée and Neveu out to his house the next day.

“He was working out of his house,” Larrivée says of Mönch. “He always worked alone. And I went there, and we were joking around. I made a comment to him — and at this point, we have to speak English because nobody else understands [French]. I said, ‘Boy, I would give anything to know how to do this.’ And he liked me, because I’m a likable guy. And he said, ‘Come tomorrow.’ It was that simple.”

By the time he met Mönch in 1967, Larrivée was, as he puts it, “already fired inside” about guitars; he wanted to know everything about the instrument. “And that invitation that he gave me,” Larrivée says, “how could you turn that down? I was never thinking of it as a profession; I just was curious. The first day I started working with him, he hands me wood and he says, ‘That’s gonna be your guitar.’ The first five minutes that I worked with him, I was building my first guitar.”

Larrivée spent about a year and a half at Mönch’s side, during which time he built his first two guitars, both in the classical style (and both of which he still has today). In 1968, after leaving Mönch, Larrivée began building guitars commercially in his own small shops around Toronto, and for the next four years, he only built what he calls “classic guitars.” The steel-string designs for which he’d become renowned were still a thing of the future.

The year 1972 was pivotal for Jean Larrivée, thanks to the influence of an American draft dodger named Eric Nagler. That year, Nagler convinced Larrivée to build steel-string guitars — and he also introduced him to an art-college student named Wendy Jones, who would marry Larrivée that very same year. (Their honeymoon, a four-day car trip to Vancouver, marked the first time that Jean Larrivée “traveled for wood.”)

When Jones first crossed paths with Larrivée, she was a woodworking student at Royal Ontario College. “I had some friends who were Celtic musicians,” Wendy remembers. “I decided that, for a project, I wanted to make an Appalachian dulcimer. One of those friends built dulcimers. He took me to the Toronto Folklore Center, and Eric Nagler at the Folklore Center took me to meet Jean to buy the wood.” Jones would eventually become Larrivée’s indispensable partner in the guitar enterprise, making Larrivée Guitars a true “family business.”

Toronto born and bred, Wendy Larrivée has for many years been instrumental in designing and engraving the inlay patterns on Larrivée’s high-end guitars; she is also the COO and vice president of Larrivée Guitars, although one is quick to discover that titles don’t mean that much around these parts. “Jean’s talent is for reaching outward to new endeavors, reaching outward quite freely,” she explains, “and I, on the other hand, am the person who kind of grabs him by the coattails and says, ‘Oh, wait a minute,’ and I try to hold him on the face of the planet, right? I think that we’re kind of a yin and yang between us.”

All of the Larrivée children “came up in the business,” she adds. “We would talk business at the dinner table, we would talk guitar design. When they were too young to go to daycare, they came to work with me. Matthew [would be] sitting on the floor while I was doing inlay, and he was taking apart machines that we would buy for him at the surplus store. That was his playtime. And they’re all just the same.

“Work time is family time.”

Matthew is now the one who runs the show in Oxnard when papa Jean is off in search of the next wood stash. His older brother, John Jr., is in charge of the plant up in B.C. “I grew up in the shop,” says Matthew. “That’s where I spent my weekends; that’s where I spent evenings. My dad would go back to work at night, and I’d go with him. And I’d work summers since I was probably 10 or 11, just doing random things. Anything from pearl cutting to sanding, helping my dad rope bodies.”

As a young boy, it was easy for Matthew to be impressed by his father’s mechanical acumen. “My dad did a lot of different machinery building in our basement for his factory,” he recalls. “You know, when you’re left alone to create, you can create some pretty interesting things. . . . It was fascinating as a kid to see that kind of development.”

Matthew became a full-time employee after high school. Proficient with computers (and with a background in pearl cutting), he was instrumental in programming the company’s CNC machines, helping to automate some of the more monotonous tasks in the shop. (“Not to automate the construction of the guitar,” he explains, “to automate the processes that help make the parts that people can use to build the guitar better.”)

When the factory opened in Oxnard, Matthew jumped at the chance. “Living in California and having the opportunity to work side by side with my dad in a small shop again,” he says, “it was a perfect opportunity and something that I had to do.” Matthew’s young son and daughter are the first Larrivées to be born in the United States, a fact that brings him much pride.

Back in ’72, though, a large, blossoming family business was not likely what Jean Larrivée had in mind — until his pal Eric Nagler intervened. Nagler had come to Canada in 1968 as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. (He faced trial in the U.S. in 1972 and was acquitted.) Nagler is now the Juno-nominated star of a series of children’s recordings and videos known as Eric’s World.

Nagler opened the Toronto Folklore Center — modeled in part after the one in New York — to be a focal point for the folk-music community, a place where pickers, builders, buyers, teachers, students and, apparently, other draft dodgers could congregate. According to Grit Laskin, an early Larrivée apprentice and today a well-known builder in his own right, Jean Larrivée was “camped out” on the third floor of the Folklore Center when he met him in 1971; Nagler had allowed Larrivée to live above the shop while Larrivée was going through a divorce from his first wife.

It was Nagler who started Larrivée on the steel-stringed path. “He sent me to New York to meet Matty Umanov,” Larrivée recalls, “and then after that, I went to the Martin Guitar factory. I saw that, Wow, they make guitars just like I do. Even though mine were classic guitars, the techniques were exactly the same. It was mind-blowing.”

The only difference that he saw between his classical models and the steel-strings he was learning about was the bracing. “The dovetail, the lining, the way they glued the fingerboard, the way they carved it,” he says, “everything was exactly the same.”

That trip would have a significant impact on Larrivée, personally and professionally. (For one thing, Larrivée and Umanov became so close that Larrivée named his son Matthew after Umanov.) “I think the goal was to enlighten me,” he says of that seminal journey, “because I was already doing quite well with classic guitars and really didn’t have any plans to grow. But I was quite intrigued by [steel-strings].” He returned to Toronto and immediately began building steel-string guitars.

“I made a couple dreadnoughts and some junior dreadnoughts,” Larrivée says — dreadnoughts being a kind of guitar builder’s initiation. “At that point, I was using sort of the Martin bracing, and I think I only made a few of those guitars. Then I started using my own bracing, because of my left-handed situation. . . .”

Larrivée’s unique symmetrical bracing pattern is one of his two most crucial acoustic-guitar innovations — and he came about it mostly by chance, simply because he was a lefty. Since about 1945, Martin’s standard X pattern had been the customary style of bracing for steel-string-guitar tops. Featuring an elongated X shape and tone bars installed at a 45-degree angle, it’s an asymmetrical design. Larrivée’s creation utilizes a symmetrical X shape and tone bars that run parallel to the bridge.

“He wanted something that he could switch back and forth,” his son Matthew explains, a top that can be converted to a left-handed guitar very easily. It just so happened that the symmetrical bracing pattern had distinct sonic benefits as well. “I discovered something that was really quite unique,” the elder Larrivée remembers. “I discovered that the guitar was extremely well balanced.” A young Canadian guitarist named Bruce Cockburn, a regular visitor to the Folklore Center, agreed and became an early proponent of Larrivée’s new bracing design. “He really got me excited about it. [I thought], I’m doing something right. There’s something that I’m doing in this bracing that other guitars don’t really have.” At a time when the steel-string landscape was still dominated by Martin and Gibson, Larrivée’s idea was a major innovation in the acoustic-guitar world.

“That bracing pattern produces a really good midrange tone,” adds Matthew. “You don’t often hear people talk about midrange and balance, so you end up with other guitars out there that have one section of the sound spectrum more pronounced than others. We try for a really even mix; it’s not boomy, not twangy, it’s even across the board. It’s a recording engineer’s dream.”

The sonic enhancements brought about by Larrivée’s symmetrical bracing pattern were of especially welcome news to fingerstyle guitarists. “My guitar seemed to be well suited for that,” he says, and finger-style guitars remain the company’s true niche today. He began to build guitars for some big names on the folk scene; Tom Chapin and Peter Yarrow were early adopters. (Yarrow gave one of his first Larrivées to Judy Collins because he’d wanted one with a wider neck.)

The same spirit of experimentation that helped foster Larrivée’s distinctive bracing pattern also brought him to his second momentous innovation: the L-shape body. In loose terms, the L shape (the “L” stands for Larrivée) is a kind of fusion between a steel-string and a classical guitar. The lower bout of an L-body is the same as that of a dreadnought, but the L-body is narrower at the upper bout and waist, and the sound box is not quite as deep as a dreadnought’s either. Once again, Larrivée had come upon a vital discovery largely by happenstance, or as he likes to say, he found “success through ignorance.”

“After I’d gone to the Martin Guitar Company tour, and I saw the guitars that they were making, I just felt I really shouldn’t be making a guitar that looks like a Martin guitar,” he explains. “Isn’t that stealing? That was my point of view — I was a young man at that time, and I just felt I wanted to be more innovative.”

Until his “enlightenment” in 1972, Larrivée had never made a mold for a steel-string guitar. The process of developing a dreadnought mold was principally based on trial and error. His first attempt was uncomfortably large, the next too small, and so on. After weeks of tweaking and several different incarnations, Larrivée finally settled on what became known as the L shape.

“Accidents happen,” he says. “We created this thing, and some of it was, ‘Gee, boss, I screwed up. Look what I did.’ And I’d say, ‘OK, let’s try it.’ ”

For many years, L-body (and L-body cutaway) guitars were all Larrivée built, and the business continued to thrive throughout the mid-1970s. He was producing as many as 14 instruments a week, although the bulk of his instruments were sold in Canada and Europe, Asia, too. He moved to several different shop spaces in Toronto as his business expanded, but cracking the American market proved difficult. At about that same time, however, there was a sea change brewing in the modern steel-string-guitar industry, one that would indelibly change the acoustic-guitar market. Not surprisingly, Jean Larrivée had been ahead of the curve.

In 2008, the numberof independent luthiers and small-production guitar companies is staggering, the options for acoustic pickers nearly limitless in terms of shape and size, wood and tone, quality and cost. Yet, when Jean Larrivée launched his guitar-building business 40 years ago, he was a novelty; there was really no such thing as a “boutique acoustic guitar.” “I’m pretty well the oldest guy in the industry,” Larrivée notes.

In the mid-1970s, as Larrivée continued to ply his trade up north, independent American luthiers such as Bob Taylor and Santa Cruz Guitar Company’s Richard Hoover started to challenge the Martin/Gibson hegemony. By developing their own enhancements and modifications to “classic” steel-string designs, luthiers like Taylor and Hoover found that they were able to slice into the big boys’ market share.

That pioneering generation of modern luthiers remains exceptional in acoustic-guitar history; they were bold enough to experiment, but still well schooled in guitar-building traditions. But more than that, there was a generosity of spirit, a deep notion of camaraderie, that defined them, and it was that willingness to share ideas, to actually help your ostensible competitor, that allowed the boutique movement to truly flourish.

Bob Taylor, whose own company has become a market leader, met Jean Larrivée at the 1977 NAMM show. The two builders shared a distributor — Rothschild Musical Instruments, the brainchild of music producer Paul Rothschild — and the idea at the time was to gather several small-production builders under one entity to increase their sales and marketing power. The idea didn’t ultimately pan out, but Taylor and Larrivée became lifelong friends.

“I began making guitars at the dawn of the small-time American luthier,” Taylor explains. “If you start building guitars today, you can buy any one of 200 books or videos on the subject, along with all the tools and supplies. You can attend schools, lectures and symposiums.

“When Jean and I started, there was one book available and no supply houses. We found out how to do things from each other. It was easier and more natural than finding out from a few large factories that had existed for decades, as they were not in the business of teaching people how to build guitars.” The building brotherhood of that era seems remarkable today. An important innovation or discovery, a useful shortcut or flash of design inspiration, was something to be shared, to be bragged about.

“There was no threat between Jean, myself, Santa Cruz, etc., and we were our own support group,” Taylor continues. “It was our sheer love and interest in the craft that caused us to talk and learn from each other . . . We knew nobody else in our lives that could appreciate our ingenuity except other guitar builders. “Only another guitar builder had the potential to be a great friend.”

Larrivée, too, realizes that he was part of something special. “It was a generation that probably will not repeat itself,” he says. “I think my doors have always been open, and Taylor’s as well.” Larrivée realizes that today’s scene may not be as tight as it used to be; as the builder community rapidly expands, younger luthiers are somewhat hesitant to share their wisdom. “In the young days,” notes Larrivée, “we were all friends and anxious to learn. Now, the group is so much bigger — there are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of guitar builders.”

Larrivée’s old apprentice Grit Laskin remains astonished and inspired by how generous Larrivée was and is with his knowledge. “Builders who were just starting or building part-time or whatever it was — they’d come in the shop with their problems,” Laskin says, “and Jean would stop what he was doing and help them through it. Or he’d say, ‘Well, why don’t you come over next week, and we’ll glue the back on here, and I’ll show you how to do it.’ Or, ‘Here, copy my dovetail jig.’ I witnessed that kind of attitude. He never did hold back and say, ‘Hey, come on, I’ve been working for X number of years, and I’m just not gonna tell you.’ ”

Laskin sees that same mindset from Bob Taylor. “He’s another person of that ilk,” Laskin says, someone who’s confident in his work and someone who understands the ultimate “truth” about guitar building: “Even if I had you in my shop tomorrow,” Laskin quips, “and you were building a guitar precisely based on my design — in my shop, with my wood and tools — it wouldn’t sound exactly like mine.”

Taylor is proud of the legacy that he and Larrivée and their generation of luthiers have left behind. “Today’s boutique luthier benefits from what we forged,” Taylor asserts. “We paved the way for this to happen. We were the pioneers, and anyone younger than 40 years old would never know these things about Taylor and Larrivée, because we’ve always been there. They see us as corporations that came from who knows where.”

While the acoustic-guitar landscape was rapidly changing in the States — thanks in part to people like Bob Taylor — Larrivée’s design innovations hadn’t quite caught on south of the Canadian border. “The American market was ridiculously hard to break into,” Larrivée says. “Everything was Martin, Martin, Martin, Gibson, Gibson, Gibson, and nobody wanted a Larrivée. What the hell kind of name is that, you know? And look at this funny guitar — it doesn’t even have a pickguard.”

In 1977, the Larrivées — their crew of about half a dozen in tow — decided to head west for good, and they set up shop in Victoria, British Columbia, on Vancouver Island. The Larrivées were attracted by — what else? — the wood supply. “Vancouver Island was paradise for us because we had all the wood in the world,” Larrivée says. The coastal forests of the island yield spruce and cedar that are some of the most desirable tone woods around. In addition, the Larrivées appreciated coastal B.C.’s mild climate (as did their wood) and wonderful scenery.

The burgeoning company stayed on the island until 1982, and production in those years got as high as 20 guitars a week. Larrivée’s signature L-body continued to earn glowing reviews from fingerstyle players, thanks to its wide fingerboard, long scale and blend of power and balance. “I got into [building] really seriously when recording studios started using them a lot,” he points out. “People would buy these guitars and end up in a recording studio and not have to do any mixing at all. The whole thing was just, walk in, sit down, play.”

For whatever reason, though, the L-body simply didn’t capture the imagination of American players. Larrivée was still committed to breaking into the U.S. market, but he realized that he needed to branch out. “I couldn’t do it with the L-shape,” he states flatly. “Nobody wanted it.”

Larrivée moved his business to North Vancouver in 1982, and he stayed in the East First Street shop for about a decade. Though the space was small, it was a period of expansion and experimentation. With the acoustic market facing a major downturn in the 1980s, he started to build electric guitars, a decision that was chiefly responsible for his move to the mainland, and the company produced roughly 13,000 electrics in five years’ time. (At this year’s NAMM show, Larrivée announced his return to the world of electrics, unveiling the RS-4, a solid-body electric with maple top, mahogany body and neck and two Lollar hum-buckers.)

As the acoustic market bounded back in the 1990s, Larrivée began to expand his acoustic line, first adding dreadnoughts and orchestra models (OMs), then jumbos, too. He also started making ukuleles for about three or four years in the latter part of the decade; they proved to be rather popular in Japan and gave Larrivée’s business a welcome boost — until the demand cycle abruptly ended. (The company is currently considering another stab at the uke market.)

In 1993, Larrivée bought a 10,000-sq. ft. space closer to downtown Vancouver — known as the Victoria Diversion shop — where 82 employees were pumping out instruments for Guitar Center, among other outlets. About 10 years ago, Larrivée moved the business to the sprawling Cordova Street factory in Vancouver, which peaked at a workforce of 180, and the Canadian arm of the company remains there today.

For all his growth and success, the Canadian native still had one elusive conquest on his mind as the new millennium approached: Jean Larrivée Guitars USA.

Jean Larrivée may now make his home in Southern California, but he will be forever considered by many to be the father of modern Canadian lutherie. Fellow Canadians such as Grit Laskin, David Wren, Linda Manzer, Ted Thompson, Sergei de Jonge and Shelley Park have all studied under Larrivée at some point, and now all of them are respected builders on their own.

Although he enjoyed a legendary status among Canadian guitar builders and buyers, Larrivée remained eager to tap the U.S. market. He began to expand his acoustic line even further, making 0s, 00s and 000s — “everything but the kitchen sink,” he says. By the end of the 1990s, Larrivée knew for sure that he wanted to immigrate to the States, and so cracking the American market became more vital than ever.

Finally, in 2001, he realized a longtime dream when he opened the doors to Larrivée USA. He’d gotten several attractive business-development offers from Southern states like Kentucky and Tennessee; South Carolina offered him a 100,000-sq. ft. facility virtually free of charge. Still, despite the high cost of everything in California — from housing and energy to shipping rates and workman’s comp insurance — the Golden State still beckoned.

“Everything is against you,” Larrivée says of his new home, “but it’s a lovely place to live.” Adds wife Wendy: “There’s something orderly about the California landscape that just really attracts me; something doesn’t grow if you don’t water it. It’s not like in wild, rugged B.C., where everything grows so immensely.” She is quick to add that “California loves the entrepreneur.”

Larrivée’s initial choice of destination was Redding, in the central valley of Northern California, but the temperature extremes made it an impractical choice. Another choice was San Diego — but that was Taylor territory. (“I didn’t want to upset the apple cart,” Larrivée says.) The family eventually settled on Oxnard, in Ventura County, and has been quite pleased with the decision. (In fact, Larrivée proudly shows off the Entrepreneur of the Year award that he received from the Oxnard City Council in 2006; it is one of his very few office decorations.)

If you want to visit the Oxnard factory, you better make sure you know the exact address, because there is no sign on the building. “Atención,” says a small sign in the tiny lobby. “Usted necesita papeles legales para trabajar aqui. Gracias.” The Oxnard employee roster is 30 percent to 40 percent female — an unusual ratio for a guitar company — and most of the women are of Mexican descent, with very limited English skills. “The women workers here are very talented, and they’re here every day,” says Wendy Larrivée. “And they push the numbers, and they’re really good.”

At the Oxnard facility, there seems to be a clear division of labor; the women tend to do the more finely detailed work — binding, kerfing, joining tops — while the men do jobs that may require more arm and wrist strength, like buffing, for example. The women seem quite happy with their jobs at Larrivée, which offer them a welcome alternative to agricultural work.

“If you get a job where you can be indoors sitting down,” Wendy says, “doing something that you feel pride in — as opposed to being out in the field and picking strawberries — you’re gonna make that choice. You don’t have to be a musician and love guitars to want to do that, right?”

Today, Larrivée’s high-end instruments are constructed and assembled in the Oxnard shop, while the Vancouver factory handles their satin-finish guitars (although guitars are often sent down from the Canadian factory for finishing touches in Oxnard, and many of the parts for the Oxnard instruments are made in Canada). In 2006, combined production for the two facilities reached 50 instruments a day. Currently, the Oxnard shop is producing approximately 18 and Vancouver is making about 26 on a daily basis.

Since the American side of the business opened nearly seven years ago, Larrivée has increasingly turned his attention to building high-end instruments. Larrivée’s recently developed Traditional series, featuring slotted headstocks with volutes in the back, reflects that new focus. As part of the series, he added an SD (slope-shouldered dreadnought) and an elongated 000 to his product line, to augment his established L-bodies, dreadnoughts and OMs. (The company builds small-body L-shapes and parlor guitars as well.) “All these models were just to try to stimulate sales, especially because now I live in California,” Jean Larrivée says. “Now, it’s an American guitar company — this company is completely separate from the Canadian guitar company — and so we started making American-style guitars.”

Perhaps, then, it’s a bit ironic that Larrivée’s unique L-body has once again become his most popular model, still beloved by fingerstylists around the music world. “The L-body is what we are,” Matthew says. “That’s my father’s creation.”

Next item on the agenda for Jean Larrivée: mandolins, which began rolling out of the shop this year. During a visit last fall, there were about 250 mandolins in the Oxnard shop in various stages of development. Although he invested $500,000 in the mandolin initiative in 2005, Larrivée has been in “no rush” to push the instruments to market. (“If you jump the gun,” he says plainly, “it will wind up biting you in the ass.”) Instead, it’s been a slow evolution as Larrivée figures out the idiosyncrasies of mandolin building. (“I have to learn it myself first,” he offers, “then I can teach everyone else.”)

“Mandolins are a very tricky instrument,” explains Matthew. “You’re trying to make it special, a little bit different, but not stray from the traditions.” Therefore, they are taking their time, tinkering with the bridge, the bracing, the binding and the like and finding the right combination of hand-building and CNC work.

And then there’s the color. Larrivée perseverated over the perfect blend of stain and varnish for months. “He spends half his Sundays, when he’s in town, sitting there painting mandolins and getting the staining just right,” Matthew says. Learning mandolins has been a painstaking process for his father and for the company. “We’re reinventing the wheel in a sense, but that makes it our own.” (Larrivée, incidentally, finally settled on a super-thin, specially formulated varnish that is banned in California and requires an additional permit.)

It’s just the kind of compulsive behavior for which Jean Larrivée has become known — and revered. Bob Taylor praises his creativity — in both design and construction method — along with his robust work ethic. “Jean isn’t trying to get out of working,” Taylor says. “He is involved in every aspect of his company.”

Linda Manzer appreciates his energy level, his fearlessness — and the deft touch of his hands. “He once had to pull a huge, deep sliver out of my finger,” she relates, “and it was either go to the hospital or have him do it right then and there. I trusted his hands so much I let him take a scalpel to my finger. I remember thinking as he began working on my finger, He could have been a brain surgeon. He was that good.”

Grit Laskin believes that Larrivée’s modest upbringing has given him a “drive to succeed” and a desire “to be a larger entity,” factors that only have seemed to enhance the quality of Larrivée’s work. “I consider myself lucky, extremely lucky, that fate put me in his path,” Laskin says. “I learned from somebody who had very high standards of workmanship.”

Larrivée’s talents are not lost on his current employees either. Chuck Downe, who supervises the finish shop in Oxnard, has been in the guitar business for 25 years, including stints at Rickenbacker and Tom Anderson Guitarworks. (With his bushy “walrus” mustache, well-worn Anderson shirt and long hair poking under an Elixir Strings cap, he certainly looks the part.)

Downe is impressed by his new boss’ superior attention to detail and his integrity. “He’s very meticulous about what he does,” Downe says. “He wants things done just exactly a certain way. I mean, he’s constantly going to different places to buy the raw wood, instead of hiring somebody to send it. He actually goes there and makes sure it’s what we want.”

Larry Lingle has been with Larrivée for seven years; in fact, he moved from the Vancouver shop with the company and helped Larrivée assemble the Oxnard factory. “He’s a building animal,” Lingle says of his longtime friend. “Almost every single guitar that comes out of here — and we’re heading out towards 100,000 now — has been touched in some way by Jean.” Larrivée may cut the wood, rout the binding or carve the neck, among other things, and he’ll probably do it more efficiently, too. “Our neck fitter typically does around 16 to 20 guitars a day,” Lingle claims. “Jean has done 71 guitars in one day. [He’s] fretted over 60 guitars in a day. It’s like he’s nuts.”

Lingle likes to tell the tale of when Maui-based luthier Steve Grimes turned Larrivée on to a desirable reserve of Hawaiian koa. “Apparently,” Lingle says, “they don’t really like outsiders there, because they’re native Hawaiians, and it’s their wood. So you have to get on their good side. A lot of times, they won’t even sell stuff to outsiders, but Jean went over there and made friends with them. After they found out that he was OK and he knew what he was talking about, he went out in the rainforest with them for a few days, got all wet and mucked up in the mud and cut down trees with them. I seriously doubt if you’ll see any other builder of a company this size doing that kind of stuff.

“It is pretty hardcore, getting out there with a chainsaw . . .”

Physically speaking, Jean Larrivée does not cut a particularly tall or imposing figure. Sporting a t-shirt and jeans, a gray beard and round glasses, his long gray hair in a ponytail, Larrivée has a gentle demeanor and a benign smile, but there is clearly a fire and intensity simmering just below the surface. “I’m very fortunate to have the skills that I have,” he says while sitting at a table in his spartan office. (Approximate contents: one laptop.) “Chief, cook, bottle washer, right? I can do just about anything — plumbing, electrical. If my car breaks down, I can fix it.”

Consumed by his work, Larrivée has no hobbies and he has no holidays. The last thing in the world he’d want to do, he says, is “go to the Bahamas for holiday.” Instead, he’ll just continue to perfect his craft, a craft that’s been his passion for more than four decades. “If I had a holiday, I’d probably stay home and cut the grass,” Larrivée says. “I’m always on the go. I got home yesterday, I’m leaving tomorrow. You see me today, I’m working and working and working, and I’ll work tomorrow because my flight’s not ’til late, late, late . . .”

Sidebar: Monch, Larrivee and the Canadian Contigent

Generous with his time, willing to share ideas and highly supportive of young craftspeople, Jean Larrivée helped spawn an entire generation of Canadian guitar builders. Grit Laskin toils in Toronto, and so does Linda Manzer. Sergei de Jonge can be found in the hamlet of Chelsea, Quebec, just across the border from Ottawa, Ontario. Shelley Park makes her Selmer-Maccaferri-style beauties in Vancouver, and Ted Thompson’s workshop is about 275 miles to the east, in Vernon, B.C.

Each of these luthiers spent some time at Larrivée’s side, learning the fundamentals of building, before launching successful solo careers in the lutherie business. While they’ve all developed individual building styles to varying degrees, they also share a common foundation, a foundation that traces back to Edgar Mönch.

Born in Leipzig, Germany, in 1907, Mönch started building classical guitars in Munich in the 1940s. While he was acquainted with pioneering guitar maker Hermann Hauser and son Hermann Hauser II, he never officially worked with them, although he did study briefly with the venerable Spanish builder Marcelo Barbero. Mönch’s reputation as a talented luthier grew throughout the 1950s. (Both John Williams and Julian Bream played Mönch instruments at points in their careers.) In 1965, Mönch pulled up stakes and landed in Toronto, where he opened his new workshop.

If Jean Larrivée is the father of modern Canadian guitar building, then Edgar Mönch must surely be the grandfather. It was a chance meeting with Mönch in 1967 that set Larrivée on the lutherie track. When Larrivée, during a visit to Mönch’s home workshop, rhetorically expressed an interest in learning how to build guitars, the master invited him back the next day — to start apprenticing. “He was a great guitar builder,” Larrivée says, “so you can imagine everything was by hand — fret slotting, all that stuff. These were really, really expensive guitars, so I learned the hard way. . . . I’m very happy that I learned it that way because it also gave me new skills: to be able to manipulate wood in any shape, way or form. No one really figures out [on his own] how to bend wood, how to plane wood, and everything had to be done by hand.”

For Larrivée, simply learning how to process his raw materials was most vital, but he also learned a lot about bracing, painting and all of the other bits of detail. Larrivée compares his experience with Mönch to learning a new language and the numerous steps it takes to turn words and grammar into a greater whole. “Edgar used to love to talk,” Larrivée remembers, “and so he would teach me all these things, how to bend wood. My God, this was such a foreign thing to me, and for him to just stand there and be able to bend wood while he’s talking to me? Then it’s my turn to bend the wood, and it’s like, ‘Oh my God, this is not so easy.’ ”

Larrivée stayed with Mönch for a year and a half, although he says now that he learned pretty much everything there was to learn about Mönch’s construction methods within the first three months on the job. “I knew exactly what I was doing,” he says, somewhat paradoxically, “I just didn’t have all the skills yet.” Dedicated as always, Larrivée kept his day job as a mechanic while he learned the tricks of the luthier’s trade from his mentor. “I didn’t have much of a social life,” he says of his tenure with Mönch. “That was my life.”

It was during this period that Larrivée’s own concepts about body shape and bracing first began to crystallize. Grit Laskin, who would apprentice with Larrivée a few short years after Larrivée worked with Mönch, notes, “There’s a lot about [Larrivée’s] designs, even today, that are reminiscent of Mönch. But I think he’s proud of that fact, and it indicates the continuation of a line, in the same way that some of Mönch’s designs were influenced by the people he worked with.” (In a nice bit of symmetry, Mönch’s nephew, Kolya Panhuyzen, an esteemed builder himself, learned a great deal about his craft from Larrivée, his uncle’s star pupil.)

Laskin’s own designs owe a debt to the work of Mönch and Larrivée. Laskin met Jean Larrivée at the Toronto Folklore Center in 1971 and was with him when Larrivée strung up his first steel-string. Laskin remembers how Eric Nagler at the Folklore Center and others had been pushing Larrivée toward the steel-string business. “Jean really wasn’t ready for it at that point,” Laskin recalls. “He was just a classical-guitar maker; that’s all he knew. He’d played classical, so he learned how to build one.”

Laskin was a “hairy, scruffy teenager” when he first espied Larrivée’s guitars at the Toronto Folklore Center. “That was the moment when it first hit me that instruments were made by humans, that hands actually made this thing,” he says, and he was instantly intrigued by the construction process. “How does somebody accomplish something like that?” he wondered. When he asked Larrivée for a job, the luthier told him, “Come on by, and we’ll give it a try.”

Laskin spent two years in Toronto with Larrivée, in what Laskin calls a “very traditional master/apprentice relationship.” (The pay arrangement was an informal, “Hey, Jean, I could use some dough” kind of thing.) For the bulk of those two years, it was just Larrivée and Laskin.

“He was up on the third floor [of the Folklore Center] on a piece of plywood, with a piece of foam for a mattress,” Laskin remembers. “That’s where Jean was living, and I was renting a couple blocks away. I’d climb up to the third floor, knock on Jean’s door, wake him up, go downstairs to the greasy spoon next door and get some rye toast and coffee. We’d sit on the edge of his bed and have breakfast, and then we’d walk the 10-minute walk over to his shop. By then, it’s maybe 11 in the morning, and we worked ’til midnight. And that was my life, six, sometimes seven days a week, for two years. “And we were just so into it, I was high as a kite.”

Larrivée by then was already deep into his obsession with tools and machinery. Laskin says Larrivée would always be buying old machines of some sort, just to tear them apart and rebuild them. “He would make new cutting blades, he would make new drill parts,” Laskin says. “Somebody who has that kind of mechanical bent and desire to tool up and play with tools . . . it was just natural that he became what he became.”

Sergei de Jonge was also with Larrivée when he made the shift toward steel-string instruments. “I was always in awe of the speed and precision of Jean’s craftsmanship,” de Jonge has said. “I don’t think I ever met anybody with better hand-to-eye coordination.”

Linda Manzer was with Larrivée during what she calls “a very transitional time” in his career. “I had heard about Jean and how he had a list as long as his arm of people wanting to apprentice with him,” recalls Manzer. “So I called several times and basically bugged him until he hired me.” Manzer was one of the handful of employees who made the journey from Toronto to Vancouver Island in 1977. “He went from small — with only four or five employees in a funky, fun shop in Toronto, where we even had time to enjoy being on a silly hockey team — to Victoria and a more factory-like setting, with about 12 to 15 employees on double shifts by the time I left.”

Larrivée has fond memories of the trip west and the crew that came with him. “It was a great time because it was a great little family we had,” he says. Working with Larrivée, Manzer appreciated his “European classical design sense” and was especially struck by his attention to detail and the cleanliness of his work. She still incorporates ideas from Larrivée’s symmetrical top-bracing pattern into her own work today. “The apple doesn’t fall too far from the tree,” she says.

Interestingly, however, while Larrivée has focused much of his energy on the growth and expansion of his business, his disciples seem more content to keep their “boutique” operations more modest-sized. “I saw what happens when you introduce more people into the building picture and the impact that has on the work,” Manzer says. “And as a result, I firmly made up my mind to keep my shop personal. To each his or her own, but for me, a small, intimate setting was and still is where the magic lies.” Larrivée, adds Grit Laskin, “chose to go [the large-business] route versus the route I’ve chosen, which is the complete opposite end, a very exclusive one.”

While their business principles may diverge from his, Larrivée’s students continue to breathe life into Canadian lutherie. Laskin, for one, believes that the open-mindedness of Canadian guitar buyers, especially in the 1970s, helped nurture the innovations that Larrivée and his followers have devised. While American guitarists took little interest in any instrument that strayed too far from the Martin/Gibson paradigm, Canadian players allowed their builders to feel comfortable experimenting with new approaches.

“Jean did his own designs and pulled it off,” Laskin says. “Maybe it’s because we were in Canada, so there wasn’t quite as extreme a prejudice by the players [toward American designs]. They were a little more open. Whatever the reason, he did come up with an original design at a time when that took some guts.”

This article originally appeared in the Fretboard Journal #10. If you enjoy in-depth articles on the world of luthiers and musicians, consider subscribing to our reader-supported print magazine.