It’s possible, if not likely, that we are living in a time when nothing matters less than the musical legacy of a Jazz musician, that discussing the influence of an artist like John Coltrane is akin to an in depth analysis of the trebuchet–something best left to the historians and NPR stations at the extreme left of the dial, so to speak. Jazz has long since been pushed to the margins, there if you look for it, but there’s no available bandwidth for it in this moment’s mainstream. If there is a player who is moving through Jazz today the way Coltrane did–starting about 60 years ago, tracing a too-short arc through a music that was still an integral part of Pop Culture–the number of people who might notice is only slightly more than the number of people who would care. For better or worse, however, we’re here for those people who care. We’re here, scribbling in the aforementioned margins, eager to consider the musical legacy of John Coltrane, particularly as it affects our little guitar-centric corner of the world.

(Top) Wes Montgomery and John Coltrane at the Monterey Jazz Festival, September 24, 1961, © Jim Marshall

(Above) Coltrane during the recording of “Kind of Blue” with Miles Davis, Photo: Don Hunstein

And it’s massive, you know. Coltrane’s fingerprints can be found all over guitar players and the music they’ve made for the past half-century plus, from Jimi Hendrix to Duane Allman to Tony Rice. There’s a lot to point to: the sound, the ambition, the little bits of theory that translate so easily to a guitarists’ technique (modal harmony, pentatonic scales, etc.) and, of course, the covers: from the classic Wes Montgomery version of “Impressions” (a song also well-covered by Pat Martino) to Pat Metheny’s take on “Giant Steps,” numerous versions of “Naima,” by artists like George Benson and Derek Trucks (an avowed Coltrane acolyte who has also recorded “Mr. P.C.”), “Lazy Bird” by Kurt Rosenwinkel (as well as Peter Bernstein and Joachim Schoenecker, and arranged for The Two High String Band by the legendary Alan Munde), the album Love Devotion Surrender by John McLaughlin and Carlos Santana (described by the critic Ben Ratliff in his indispensable book, Coltrane: The Story of a Sound, as “big-boned, pneumatic, athletic jazz-rock, a direct aorta to later fusion guitarists like Allan Holdsworth and, by extension, to a heavy-metal aesthetic that persists today”) and, way over at the very edge of the margins, Nels Cline’s ambitious and illuminating recording with drummer Gregg Bendian, Interstellar Space Revisited. Meanwhile, there’s the influence of guitarists on Coltrane, lurking a little deeper (he studied with the swing guitarist Dennis Sandole), not to mention Coltrane’s work with guitar players: numerous sessions as a sideman in groups with guitar players in the ‘50s (often Kenny Burrell, with whom he was co-leader for an excellent eponymous release, but also with Freddie Green, Earl Bostic and others), as well as a lone performance with Wes Montgomery and Eric Dolphy augmenting Coltrane’s “Classic Quartet,” at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1961, performing a set that included “Impressions,” perhaps planting the seed for Montgomery’s later recording (a tape of the set reportedly exists but has not been released).

So, with July 17th marking the 50th anniversary of the passing of John William Coltrane, we’ve reached out to a few guitar players we admire and respect to pay tribute and help us understand Trane’s influence: the aforementioned Nels Cline; Jon Herington, guitarist for Steely Dan and others, as well as a student of Dennis Sandole; Eric Skye, whose acoustic fingerstyle playing skirts across genres and who performed Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, an iconic recording for Coltrane as well, in its entirety at the Fretboard Summit; Vernon Reid, one of rock music’s most astounding and adventurous guitar players and a torch bearer for “Free Jazz;” Paul Asbell, another genre-defying acoustic player who recorded a beautiful arrangement of “Naima” on his album From Adamant to Atchafalaya; and, of course, Bill Frisell, who has recorded and performed with both McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones, notable alumni of the Classic Quartet. We’d like to thank them for taking the time to share their thoughts, and for making things better, out here in the margins, where we’ve set up shop.

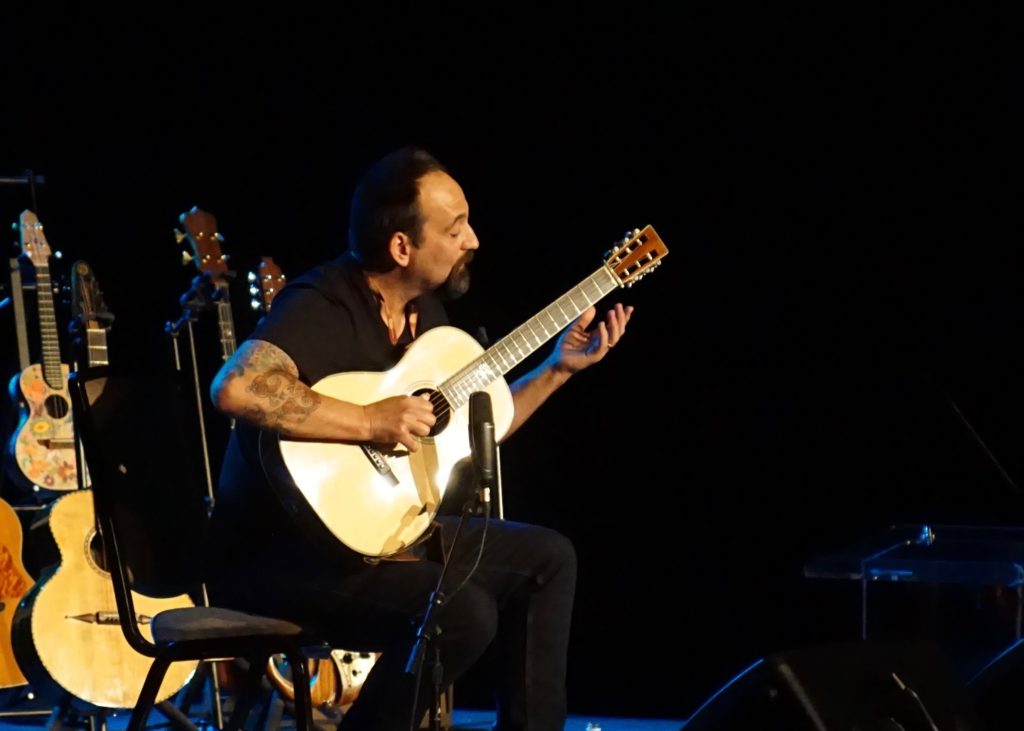

Nels Cline

There have been a handful of musical epiphanies in my life, and hearing “Africa” by John Coltrane at a friend’s apartment back in 1970 or ’71 was Epiphany Number Three (Number One being a ‘live’ recording of Ravi Shankar played to my 5th grade class in 1966, and Number Two being “Manic Depression” by The Jimi Hendrix Experience, heard on radio station KHJ in 1967). What was it about this piece of music that was so stunning? I had no inkling that “jazz” ever sounded anything like this. Of course, the arrangement by Eric Dolphy alone is a marvel. But it was something about the sound of Coltrane’s tenor saxophone–simultaneously understated and overwhelmingly powerful, sensual and ascetic–that grabbed me and has never let go. This was something SERIOUS. And hearing it changed the course of my life, sending me on an investigation of improvised music–so-called “jazz”–most of it not involving the guitar. The more I heard and learned about John Coltrane, the more I related him to my heroes of Indian classical music. It came as no surprise to later learn that Coltrane was deeply invested in all kinds of music, and Indian classical music was a particular favorite of his.

Coltrane’s music is music of phenomenal depth, played with total mastery. And he had gone far beyond the known parameters of jazz/be-bop/swing, etc., pushing into the realms of modal, pan-modal, and “free” music, ever searching. In essence, he was in every way the embodiment of the True Artist as well as the Deep Thinker–my kind of hero.

When Gregg Bendian and I decided to record a version of the Coltrane and Rashied Ali duets that were released posthumously as Interstellar Space I finally had to confront whatever aspects of my love of Coltrane had and would have as a guitarist. Rather like my love of Hendrix, I sort of avoided direct musical emulation of these men, thinking that I was drawing inspiration from them more than attempting actual imitation. But the realization that an overdriven electric guitar has a timbre and range very much like that of a tenor saxophone became an unavoidable fact, and I studied the melodic and sonic inventions on this and other recordings in as much depth as I could muster, as this was really a rather audacious assignment. I guess I ended up sort of imitating both Hendrix and Coltrane after all, in some ways. The music sort of leaks out that way, it seems…

A lot has been said about Coltrane’s playing, his amazing level of mastery, his discipline, his fascinating artistic directions. But last I wish to mention that his composing has had a great impact on me as well. Songs like “Alabama” and “After The Rain” (to name only two) were as moving and influential on me as Coltrane’s playing. And recordings such as Meditations and (of course) A Love Supreme influenced the way I think about form, about the way improvised music can be organized, about the balance between the composed and the spontaneous, about how to honor the individual voices of the players.

My mind is so full right now thinking about the music and life of John Coltrane, but I guess I am going to leave it at that.

Thanks.

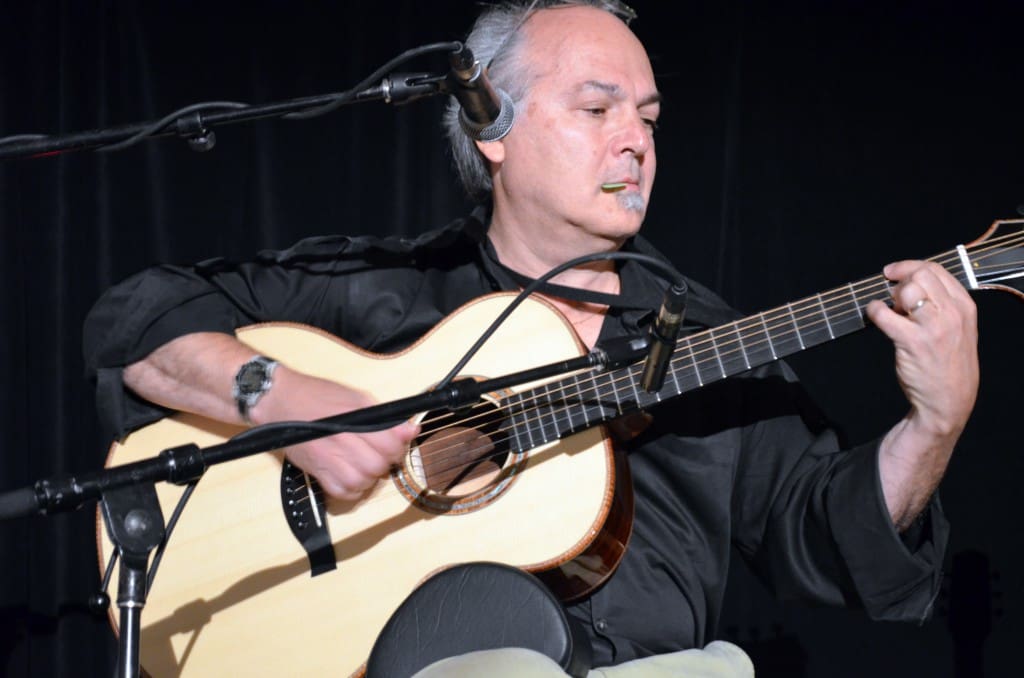

Jon Herington

Photo: Jon Gorr

Just before I began to study with Dennis Sandole in Philadelphia in the mid-’70s, a big part of my anticipatory thrill was knowing that John Coltrane had been a former student Dennis seldom talked about Coltrane to me, but when he did it was with certain pride and a big smile.In one anecdote I remember, Dennis described attending a show at a Philadelphia club where Trane’s band was booked. According to Dennis, when Trane, who was on stage playing, saw him come into the club, he immediately began to quote some of what Dennis typically referred to as “my literature” (his students will remember the use of this term, and the accompanying gleam in the Maestro’s eye). I can believe this, too, because the only player I’ve ever heard who really sounded like he completely absorbed what Sandole taught was Coltrane.

Outside of that incidental connection, Coltrane has had, and continues to have, a powerful influence on me.

I fell in love with the guitar in 1968 when I heard the sounds of the “British Invasion” players, all playing electric guitars through cranked up amplifiers. There was a very expressive, vocal quality to those sounds, a result of the way the amp allowed the notes to sustain and the way a light gauge string could be shaken and bent and made to scoop into notes, yielding a sound more like a saxophone or a cello than an acoustic guitar.

I fell in love with jazz in 1974 when I heard the sound of John Coltrane’s saxophone playing. I had listened to quite a lot of jazz players by then, but there was an unrelenting power in Trane’s playing that drew me in deeper, and led to a lifetime commitment to learning and listening to jazz.

I realize now these two epiphanies of mine are connected by the expressive power of the human voice and the capacity of melody to “light up” the musical mind. Learning to produce those sounds and listening to Coltrane turned out to be two peak experiences for me on my music making journey.

In listening to the whole breadth of his work, it’s clear that by 1964 (perhaps my favorite year of Coltrane’s), his approach sounded increasingly more “vocal;” his playing regularly included a more blues-based, vocal-like shout; and he was clearly interested in reclaiming some of the early blues and spiritual roots of jazz. He also seemed to want his playing to express a struggle or a striving, much like many blues guitar players, though unlike many other jazz players who seemed to aim for more of an effortless sounding, controlled virtuosity. I know that Trane’s approach spoke to me, and ultimately led to my refusal to give up the sound of an electric guitar through a cranked up amp, in spite of all my efforts to embrace a more traditional jazz guitar tone (still through an amp, but without the distortion that comes from cranking it up).

For a while I came to feel that jazz and the traditional sounds of jazz guitar were like my second musical language. I had started out with the language and the sound of blues and rock guitar, and in a way, for me, jazz and most jazz players’ sounds felt like an adopted tongue. But eventually I came to feel that the style of music was less important than the feeling of having a natural, expressive power as a player. Coltrane has often been a great reminder of that: In both of those epiphanies I had fallen in love with the way instruments can imitate the human voice, and to this day the blues and rock sounds of the electric guitar feel like my most natural, expressive tools for making music.

Vernon Reid

Photo by Zack Whitford

John Coltrane’s combination of extreme intellect and intense emotional engagement have made him a ubiquitous influence across a broad swath of instrumentalists. His technical speed has made him particularly influential to generations of guitarists of many different styles. The fact that he made the saxophone scream had a large influence on those rock & metal guitarists open enough to be influenced by Coltrane’s approach to improvisation.

Coltrane primarily influenced me by his extreme curiosity and openness to experimentation. Coltrane’s prodigious technique wasn’t an end in itself, but rather a tool for his remarkable tonal & harmonic exploration. John Coltrane took Jazz to the outer limits, and was not constrained by conventional wisdom, popular opinion, or the ridicule of his peers. All of that to search for ultimate vibration. John Coltrane set such a high benchmarks of excellence, discipline and integrity. His strong influence on two of my mentors, Carlos Santana and John McLaughlin had a massive impact on me.

Eric Skye

When I look at the life of John Coltrane I see this incredible unending effort towards growth. He was seemingly always pushing himself into new territory. Perhaps even at times to a fault, as there were points in his career where critics wrote that he sounded as if he was practicing new scales on stage. But musicians that choose the life of practice can probably relate to the burning desire to try to make that new concept work in a tune on the gig. He was a fearless artist, unafraid and, in fact, embracing of the sound of the creaking branch when out on a limb.

I appreciate and even identify with the fact that even in his most angular playing, his phrasing was always rooted in the blues, and he was just always in the zone. I think it’s impossible to overstate just how foreign it must have been to the players at the Kind Of Blue sessions, having spent their musical lives up to that point navigating tunes packed with many chord and key changes, to be dropped into the open expanse that was “So What”–16 bars of just a D minor chord, eight bars of Eb minor, then back to more D minor… I find the opening of Coltrane’s solo in that tune particularly goosebump-inducing. He comes in gigantically strong and then completely owns it thereafter.

The Atlantic era, which kicked off with an album of all original tunes, Giant Steps, was my favorite. The title track its self is a unique and incredible chord matrix that many jazz players whittle away at for a lifetime. But it’s the many great blues tunes from this period that I personally enjoy playing, such as “Equinox,” “Cousin Mary” and “Mr PC.” A little later his music shifted again, reflecting his spirituality and political views more and more. I find the music from the beginning of this period also incredibly moving. Many of these tunes–“Alabama,” “Spiritual” and “Acknowledgement,” for example–begin with these fanfares that just always get me. They are both of a time and timeless–from somewhere between the Atomic and Aquarian ages. That’s the sound of the early 1960s to me.

As he got into deeper his Impulse label recording period, he went further and further out. In the middle of this era, responding to all the uproar about his playing becoming too challenging for commercial jazz listeners, he drops Ballads–to me perhaps the most classically beautiful jazz album of all time. That record just drips with simply and lyrically stated melodies, delivered with an impossibly gorgeous tone. I love that record.

Shortly before his death, he went way, way out. Things like “Ogunde” from The Olatunji Concert are very challenging, if not frightening to listen to. But my god, when you hear it in the context of his enormous body of work leading up to it, and knowing what an intensely spiritual person he was becoming, it’s almost if he just went supernova. It’s impossible to imagine where he would have gone next.

The truth is I’ve haven’t spent much time trying to adapt any of John Coltrane’s saxophone lines to my own guitar playing per se. Nor have I gone too deep into his use of harmony, scales, etc. I’ve mostly been just an admirer. I enjoy and get deeply inspired by listening to what he did. For me, Coltrane is an oracle. Something larger than life, that I can come back to over and over to keep the fire burning.

Paul Asbell

I first heard Coltrane’s music from several saxophone players who played in my R&B/Blues band during the late ‘60’s. I could tell that their reverence for his playing, and his music, was much like the reverence I had for my own blues heroes–Otis Rush, Earl Hooker, Magic Sam, Lightnin’ Hopkins and others. At the time, however, I just couldn’t feel it.

I started getting it when one of those same players sat me down with Trane’s version of Duke Ellington’s “In A Sentimental Mood.” Unlike the complex mathematical virtuosity of “Giant Steps” and “Countdown,” here was pure emotive beauty…and what I mistakenly thought of as simplicity. THIS I could feel…and was deeply moved by it.

I soon began to work on the changes that underpinned this gorgeous tune, and eventually, dozens of others…including “Giant Steps” and “Countdown.” 50 years later, I still work daily on exactly these same skills, as virtually every player who wishes to be conversant in the jazz language does. It’s a life work…and one that teaches the guitarist the many layers of truths behind the statement, “The more one knows, the more one realizes how much one doesn’t know.”

Need a bit of humility? Start trying to play Coltrane’s music.

Bill Frisell

John Coltrane.

1968. When I was in high school I met my guitar teacher, Dale Bruning. He opened a brand new world for me and changed my life. I don’t know where I’d be now if I hadn’t met him. Dale Bruning was from Philadelphia and had studied with Dennis Sandole, who was also a teacher of Coltrane’s. Dale told me stories of what it was like going into a small club and hearing Coltrane play with Miles Davis’ groups and, later, Coltrane’s quartet with McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison and Elvin Jones. Wow.

After a few lessons he showed me John Coltrane’s composition, “Giant Steps.” I’ve been struggling with it ever since. One of the very first jazz albums I bought was The Best of John Coltrane on Atlantic (SD 1541). I also got another compilation on Blue Note–Blue Note’s Three Decades of Jazz, Volume 1, 1949 – 1959 (Blue Note, 27 018 -1)–that included Coltrane’s composition “Blue Train” and his version of “Speak Low” (with Sonny Clark).

I never got to hear John Coltrane live. To say he has been an influence would be a drastic understatement.

He has been and will always be one of the brightest guiding lights…for all of us. He changed everything. I don’t think a day goes by that I don’t think about him.

I’ve been blessed to have had the chance to play with both Elvin Jones and McCoy Tyner. Paul Motian told me about the time he filled in for Elvin at Birdland and his conversations with John. I can’t believe how lucky I am to have been that close. Whew.

I’m gonna go practice!!!

Further…

Reading

Coltrane: The Story of a Sound, Ben Ratliff (Picador; Reprint edition, 2008) – Ratliff has penned a deep dive into Coltrane the musician, breaking this essential book into two parts: the first breaking down Coltrane’s “sound” and the second his influence. We owe him a debt of gratitude for being part of the inspiration for this piece; if it piqued your interest at all you owe it to yourself to seek out this book.

Coltrane on Coltrane: The John Coltrane Interviews (Musicians in Their Own Words), Chris DeVito (Chicago Review Press; Reprint edition, 2012)

The John Coltrane Reference, Lewis Porter, Chris DeVito, Yasuhiro Fujioka, Wolf Schmaler, David Wild (Routledge, 2013)

For a pianist’s perspective, check out Brad Mehldau’s excellent essay, Coltrane, Jimi Hendrix, Beethoven and God.

Listening

We’ve included a Spotify playlist below, but if you’d prefer to dig into albums, here are a few notions (in no particular order):

Kenny Burrell & John Coltrane, Kenny Burrell and John Coltrane (Prestige, 1963)

Whims of Chambers, Paul Chambers (Blue Note, 1956)

The Cats, Tommy Flanagan, John Coltrane, Kenny Burrell, Idrees Sulieman (New Jazz, 1959)

Matador and Solid, Grant Green, with McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones and Bob Cranshaw (Blue Note, 1964)

Love Devotion Surrender, Carlos Santana and Mahavishnu John McLaughlin (Columbia, 1973)

Interstellar Space Revisited (The Music of John Coltrane), Nels Cline and Gregg Bendian (Atavistic, 1999)