The bell above the door to Adair Music Company in Lubbock, Texas, clangs as a young, bespectacled man strains to prop the door open so he can squeeze a guitar case and amplifier into the store. The proprietor, B.E. Adair, looks up, pauses tallying cash register receipts at the counter along the store’s back wall and says, “Oh, hello, Buddy. What can I do for you today?” The young man puts down the guitar and amplifier, pushes up the glasses that have slipped down a nose shiny with perspiration and says, “Well, Mr. Adair, I was in here a couple of days ago and I had a lesson with Mr. Hankins. He was playing one of those new Fender guitars, it’s called a Strato-something, I think. It sure looked slick. And, well, I got to thinking…”

The year was 1954. The young man, of course, was Buddy Holley, the spelling of whose last name had not yet been mangled by his first record label, Decca. That slick-looking instrument was Leo Fender’s just-released futuristic creation: the Stratocaster. Somehow, Holly’s occasional guitar teacher in Lubbock, Clyde Hankins, had gotten his hands on one of the earliest production models. As the guitarist stated to the Journal newspaper in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he’d lived since leaving Lubbock in the 1960s, “Buddy just enjoyed hearing me play. He never asked me to show him how to play, just some advice on chords.” Or maybe Holly was just articulating an excuse to ogle Hankins’ wild new guitar.

The guitar that Holly lugged into the shop that fateful day was the Les Paul Goldtop he had purchased there only months earlier. Some accounts have him expressing dissatisfaction with the instrument’s weight and craving the lighter Fender instrument. It’s difficult to believe, though, that he wasn’t also attracted to the revolutionary appearance of the Strat, which made his Les Paul look rather staid by comparison. As Walter Carter of Nashville’s Carter Vintage put it to me when I queried him, “Who was playing Les Pauls in 1954, other than Les Paul?” That radical Strat certainly would have called more attention to a young rock and roller playing bowling alleys and high school sock hops in the culturally and geographically isolated environs of West Texas.

Another veteran of the Nashville vintage guitar scene, George Gruhn, added in a separate conversation, “There could be any number of reasons why Holly would have wanted to play a Stratocaster,” including that visual aesthetic, the weight and playability. Other issues include intonation and the ability to dial in a proper setup.

The Stratocaster, of course, featured Leo Fender’s revolutionary six-piece saddle, which allowed for precise intonation of each of the instrument’s strings. The Les Paul, on the other hand, sported an old-fashioned trapeze tailpiece that allowed only minimal angle adjustment and, as Gruhn put it, “less than ideal intonation.” That tailpiece also required wrapping the strings under its crossbar in order to provide low action. Running the strings under that bar, though, prohibits palm muting of the guitar, a technique whose sound would feature prominently in Holly’s music.

Even under-wrapping those strings, though, didn’t always result in a comfortably playable instrument. Gibson miscalculated the neck angle, or at least didn’t anticipate the setup preferences of its customers. In any event, it’s pretty much impossible to get a nice, low, “fast” setup on those first issue Les Pauls. Had Holly been happy with his purchase, he would have been one of Gibson’s few satisfied customers.

Then, as Gruhn suggested, “A Stratocaster can twang. A Les Paul can do many things, but it can’t twang.” Imagine, for example, the chordal solo in “Peggy Sue” or that now-classic introduction to “That’ll Be the Day” played with the fat, warm sound of a Les Paul, even with the P-90 pickups of the early models. At least in my mind’s ear, it doesn’t work for the music Holly would go on to play. As Gruhn put it, “The Stratocaster was perfect for what I think Holly wanted to do. A Tele would have worked, too. But a Les Paul?”

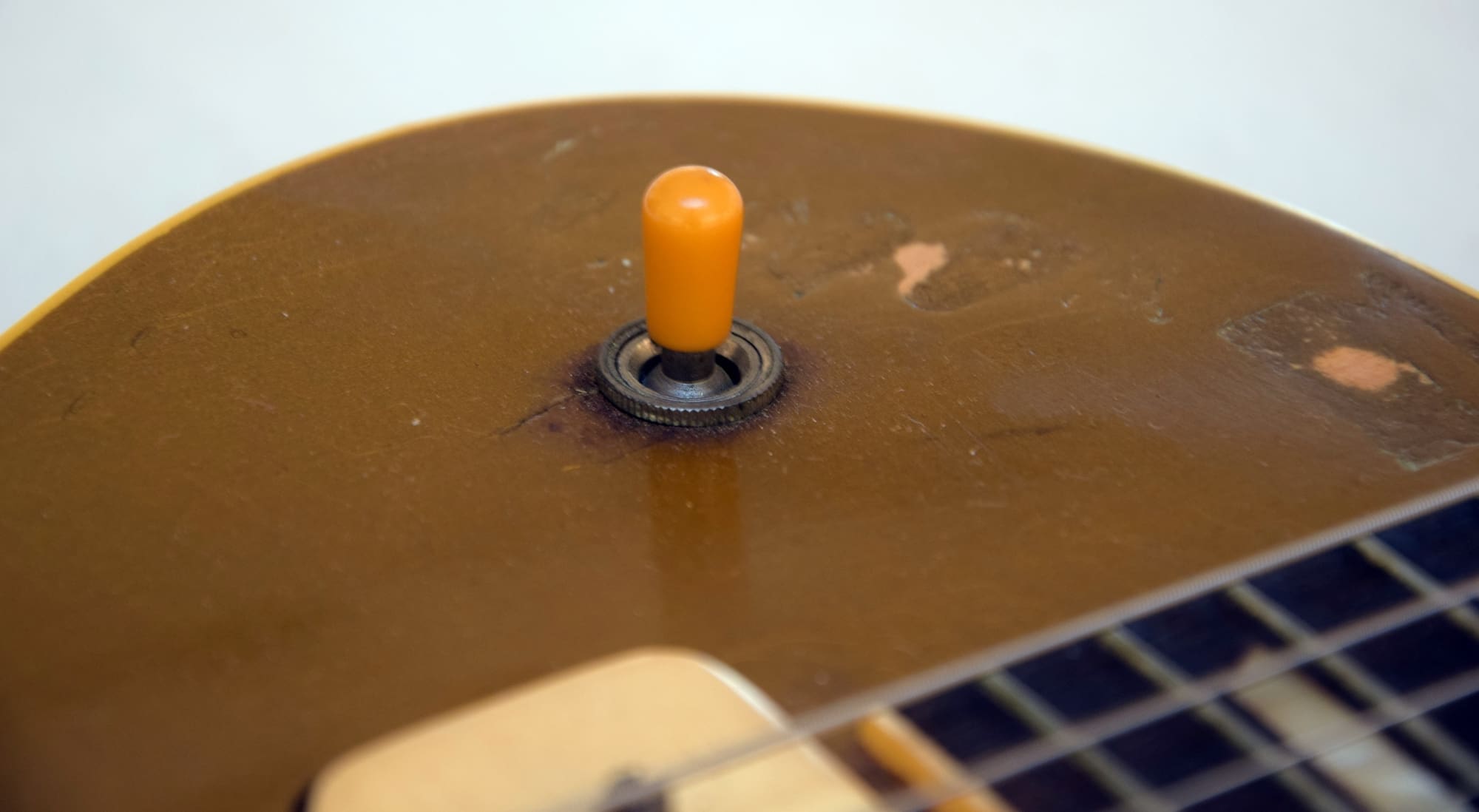

Holly’s Les Paul, Carter said, is “pretty typical” of most 1952 models. In its very first incarnation, the guitar sported no serial number, a logo with the dot of the “i” connected to the “G,” an unbound fingerboard, no “treble/rhythm” ring around the pickup toggle switch, and tall, “high hat” control knobs. By some point in 1953, serial numbers appeared stamped on the back of the headstock, that dot obtained its independence, fingerboard binding and toggle switch surround materialized and those speed dials lost some height. The amalgam of features on this guitar—no serial number, early logo, a bound fingerboard, no treble/rhythm indicator and tall knobs—places it, Carter said, “Probably mid- or even late-1952, probably before 1953.” But Gibson was clearly employing what are known in other industries as “running changes,” resulting in no clear demarcation between what are considered 1952 and 1953 models.

The amplifier, which Holly bought at the same time he bought the guitar, for a combined sum of $305, is also a 1952 “Les Paul” model, of the “G” variant, in Gibson parlance. Holly is depicted in a couple of photos playing the guitar and amp with his early “Buddy and Bob” (Montgomery) duo. No recordings in which the Les Paul is used are documented to exist. The warm sound of a Gibson amplifier, though, seems as incongruous to Holly’s music as the matching Les Paul guitar. In 1958, while living in New York City, Holly did purchase a Magnatone amp for home use, but he typically gigged with Fender amplifiers that suited his Stratocaster and twangy music to a T (for Texas, of course).

Holly scratched his name into the end of the Gibson’s speaker cone, employing the “Holley” spelling. For the sake of posterity and the purchaser of the guitar and amplifier, it’s a good thing that he did. Shortly after Holly swapped those early purchases for a shiny new 1954 Stratocaster, one Sam Logan walked into Adair Music Company. Or at least his parents did. Like Holly, Sam attended Lubbock High School. Though they were both members of the class of 1955, Logan didn’t know and does not recall ever meeting the soon-to-be rock and roll star. “I guess we didn’t run with the same crowd.” That joint life-changing event—high school graduation—did appear to serve both, though. Holly was likely eyeing life after high school when he traded for a more coveted instrument. The bespectacled one’s cast-off become Logan’s reward for completing school. Looking for the perfect graduation gift for their son in the spring of 1955, Logan’s parents snapped up the Les Paul and amp for the discounted sum of $225.

“No, I didn’t know who Buddy Holly was,” Logan, now 88 years old, explained while talking about that name scratched into the amplifier. “ “Heck, no one did then. He wasn’t a star until a couple of years later.” Thrilled with his graduation gift, Logan worked on learning some chords and eventually became an “okay” guitar player, though he was never “any Buddy Holly.”

Eventually, Logan did come to realize that the prior owner of his guitar and amp “was pretty darned famous.” Indeed, in 2001, Sam and his band, the American Time Machine, released a musical tribute to the instrument, titled, naturally, “Buddy’s Guitar.” Added Logan, “You know, if he’d never a scratched his name on that amp, I’d-a never a found out.” Find out he did, though. With the assistance of Bonham’s House, he sold the guitar and amplifier to the Buddy Holly Educational Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving Holly’s legacy. The Foundation loaned the guitar and amp to Lubbock’s Buddy Holly Center. There, staff delighted in recounting to me how happy Logan was to deliver the rock and roll artifacts to where they belong. “He almost skipped in here with them,” director Brooke Witcher told me.

So, Daddy-O, gaze upon these images and ponder where the course of cultural and musical history might have veered had Buddy Holly composed, recorded and performed his timeless tunes with these time capsules. Those revolutionary mixtures of blues, country and rock would have sounded less like that other Buddy, bluesman Buddy Guy, and more like Les Paul without Mary Ford, playing simpler licks. Like Les himself, who in his early days inhabited the hillbilly alias Rhubarb Red—and played country music and caught the attention of, well, virtually no one.

And remember on December 1, 1957, when Holly appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, giving most of the world’s music fans their first gander at a Stratocaster? Would the cats viewing their sets have flipped their wigs if Holly hadn’t been playing the ginchiest of guitars? That Strat had one classy chassis! Armed with that contoured slab of ash, Holly and the Crickets cranked through “That’ll Be the Day” and “Peggy Sue.” He was the bomb! Viewers blew their tops!

Buddy Holly with a Les Paul? That would have been the day.

Later, gator.