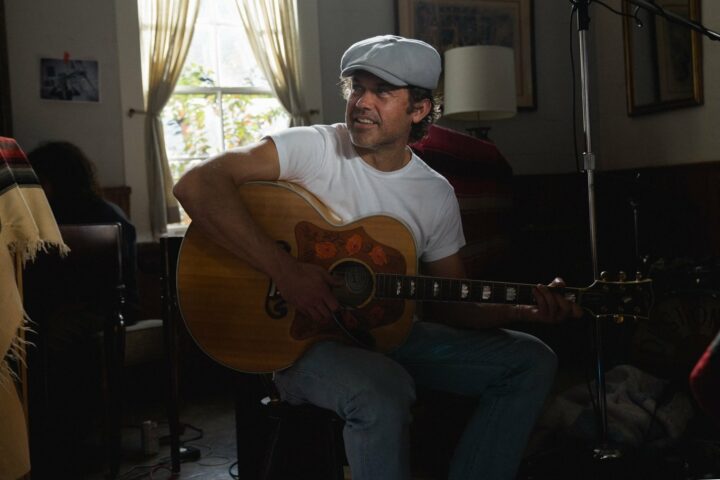

Paul Burch has never shied away from a concept. In fact, one could argue that this singer-songwriter’s entire career has carried a bit of a theme. Over the years, he’s tackled the music of Buddy Holly, created a soundtrack to a book and even transformed “Cluck Old Hen” into a Middle Eastern-tinged raga. With each release, Burch reminds us that the roots of country music (and rock & roll) come from a myriad of sources.

Which is why Burch’s 2016 project, Meridian Rising—an “imagined musical autobiography” of Jimmie Rodgers—isn’t a huge surprise. After all, Burch has symbolically paid homage to the music of Rodgers and his ilk for years. What is surprising is just how fresh and interesting this music is. Burch traces the Singing Brakeman’s short life through original songs that tell a story but also stand on their own. It’s all here: Rodgers’ beginnings in Meridian, his meteoric rise to becoming a recording star, and his tragic passing, at the age of 35, from tuberculosis. All told—through Burch—as if written by Rodgers himself.

“It actually started percolating about 15 years ago,” Burch says of his ambitious project. “I made a record called Last of My Kind, which was loosely based on the characters in a novel [Jim the Boy] by Tony Earley. The story was based in the early 1930s, so I was trying to stay in that world, thinking of the Delmore Brothers, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. Although that sounds like a narrow focus, it was also very freeing as a writer. I just remember thinking at the time that it was just lovely to not write a pop song. I could make the song as long as I needed to, depending on what I needed to say. It was a really positive writing experience.”

While Burch steeped himself in music from the ’30s, one particular tune stood out: “Let Me Be Your Sidetrack,” Rodgers’ lone recording with bluesman Clifford Gibson. “Clifford recorded for the Paramount label, he also recorded for RCA,” Burch explains. “He was a really interesting guitar player. Some of the phrasings he had, some of the open tuning and the ways that he was backing Jimmie reminded me a little of Robert Johnson. It was really wonderful to hear Jimmie’s voice over that.”

The more he thought about it, the less he thought of it as an anomaly “and more of a unique window into Jimmie’s way of thinking,” he says. “He loved the blues; a good portion of his discography is the blues. And he tended to reach out to musicians that he liked and ask them to record. He would jump on any opportunity that he had to make music with people he liked. That’s how he made his recording with Louis Armstrong, the Louisville Jug Band and many others.”

In Rodgers, Burch found himself a kindred spirit. At first, he contemplated the idea of simply covering the music legend’s best material, but that idea quickly evolved into something a bit more ambitious.

“What eventually came into my mind was trying to write from his perspective. That was exciting for me because I thought that when I did get around to it, it would mean drawing from all the kinds of music that I love from that time, everything from Jimmie and the Mississippi Sheiks to early Johnny Mercer and Duke Ellington—all the things that Jimmie would run into.”

Burch was more than a little self-conscious about this project, but friends kept encouraging him to pursue it. “Everyone I told [about the record] thought ‘that’s a good idea.’ And I thought everyone is allowed one good idea in their life.” He began to read books on Rodgers—the biography penned by Nolan Porterfield as well as Barry Mazor’s Meeting Jimmie Rodgers. “I read them the way a painter might look at a subject: I’d read an interesting fact or anecdote and then put it down and daydream about it. I found myself doing that on and off about Jimmie for many years.”

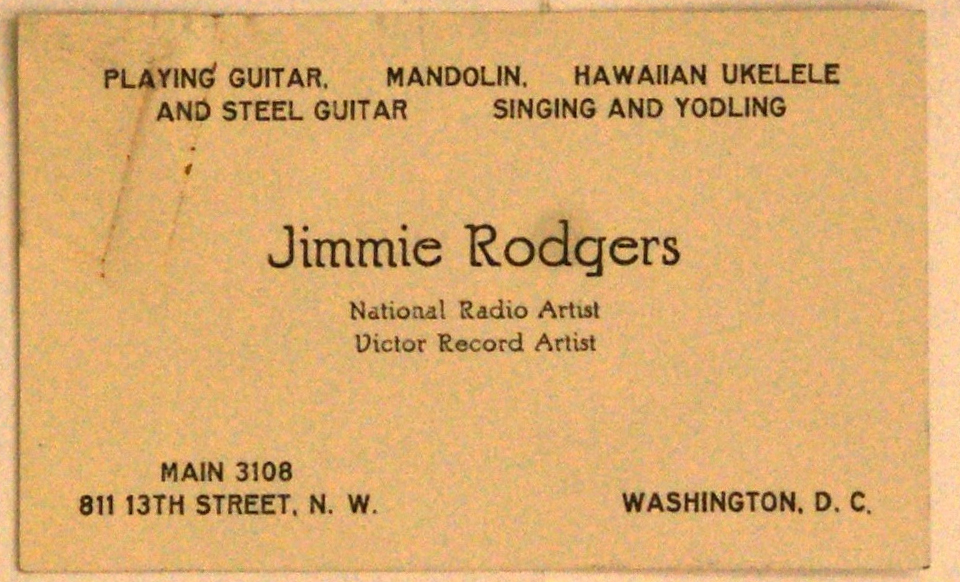

Burch also found a unique insight into Rodgers via the archives of C.F. Martin & Co. “Martin has these letters,” Burch says. “Jimmie wrote Martin a letter maybe a month after he did his Bristol sessions—still no one knew who he was, his record wasn’t even out yet. He wrote this letter, saying ‘I’m a star of radio and traveling musician and I just cut my first disc for RCA. It’ll be out next month. I just want to tell you that I think Martin makes the best guitars in the world.’ He was already trying to get a discount, like every other musician who gets a record out! The first thing you do is write the guitar company that you want a guitar from. I could see the progression: his very first letter was in pencil, his second letter was in pen, and then they were typed and then they were on his letterhead. You could see this desire to not only communicate but to be thought of as an entertainer, to be taken seriously in that way.”

As the correspondence shows, at one point in his career, Rodgers even sent his Weymann guitar to Martin’s Nazareth, Pennsylvania, factory for repair, a move that probably wouldn’t work too well these days. “He needed the bridge fixed and he sent it to Martin to get fixed,” Burch says, laughing. “I thought that was pretty funny. It was also really cool: just like any other musician, he was very interested in making sure his instrument worked correctly.”

Beyond the guitar correspondence, there’s a lot that can be read between the lines with Rodgers’ Martin letters. “He was a perennial enthusiast,” Burch says. “On one hand, he wanted to paint a rosy picture. He would very often from the road on hotel stationery write to Martin. At the end of one letter, he says, ‘Everything is fine, but I need lots of rest.’ You can almost hear him talking to himself, saying it’s going to be all right.”

Rodgers packed a lot into his 35 years. When it came to songwriting about such a complex character, Burch created an outline of sorts. “By the time I started writing, I knew the incidents in his life that I thought were worthy writing about. The first thing I did was write titles to songs, before I even wrote them,” he says. “I knew I wanted to write about Meridian, his home town. I had to tackle the fact that he has tuberculosis and that that’s what killed him. I just worked with the idea of those titles. And I was prepared to not be able to finish it. Even that was a really good attitude to have.”

Jimmie Rodgers business card, as found in the Martin Guitar archives.

Thankfully, he did finish Meridian Rising. Recorded with a couple of dozen close musical associates, it captures the vibe of Rodgers’ own recordings (minus the 78 scratches) but also sounds completely fresh. “I didn’t want it to be a precious sound, but I thought there has to be a way to be rocking and not have electric instruments…and not have them be missed, either.” Burch uses a recent Martin 000-28 on the record as a tip of the bowler hat to Rodgers (who himself used small-bodied Martins throughout his career). It probably doesn’t hurt that the project includes performances and cameos by stellar artists such as Jon Langford, Tim O’Brien, Richard Bennett, Billy Bragg, Fats Kaplin and Jack Silverman.

Burch found the whole process of channeling Rodgers refreshing and, well, fun. “If you’re making a rock & roll record, it’s easy to accidentally find yourself using an established rock record as a guide to move forward,” Burch concludes.

“If you get stuck in a song, you may think, ‘What would Neil Young do, what would the Beatles do…’ You can’t do that with writing something based on the rhythm of the Mississippi Sheiks.

“The nicest thing for me was that none of us were alive at that time. There’s no chance that we had the pressure to get it right.”

Photos by Melissa Fuller