Musicians, builders and customers reflect on an industry giant

As a musician, Bill Collings—founder of Collings Guitars—made your life easier. The guitars, mandolins and ukuleles he produced since the late ’70s raised the bar on what a production instrument could look, feel and sound like. As a result, every other builder (large and small)—whether they care to admit it or not—had to up their game. As a journalist, Bill Collings made life pretty easy, too. Here was a guy who was brimming with personality, damn funny, a stellar listener, passionate about a lot more than just lutherie, and—a rarity in our little universe—without a filter. Interviewing Collings was a breeze. You could just hit record and let him be Bill. And more often than not, the story wrote itself.

On July 14, 2017, Collings passed away from cancer. He leaves behind a legacy like few others: a shop full of builders in Austin who will continue to do his name justice; thousands of incredible instruments; and a whole lot of legendary Bill Collings stories. We reached out to friends in the industry, musicians and readers to gather a few favorites here. R.I.P. Bill, we’ll never forget you. —Jason Verlinde

I invited Bill to move to Austin in 1980, from Houston. He arrived at my place in his U-Haul truck and proceeded to start carrying boxes into my shop. I said, “You can build a workbench along that wall,” and pointed him to the lumber. As soon as he walked into the setup room with this eight-foot-long two-by-four, he swung it around and knocked the mandolin that was to go in to finish that day off the wall. I can still see it now in slow motion. Bill just stared at the mandolin as it hit the cement floor on the tip of the peghead and did a slow 180 to hit again on the tailblock. He never said a word…just picked up one of his boxes and walked out to his U-Haul truck. When he came back empty-handed, he picked up another box. I let him reload all his boxes in his truck, and he got in and said sorry, he was just going to head out to San Diego. To make a very long story short, I gave him one more chance. He moved his boxes back in and worked here in my shop until 1986. The fallen mandolin survived the fall like a champ. I wonder who owns it now? —Tom H. Ellis

My relationship with Bill was always charged with a goal or the concept of “we’re working on a guitar together…“let’s make it great.” Something tells me that was the spirit that infused every interaction he had with people. There was really no small talk. It was just to the heart of the matter, whether it was building a guitar or discussing life in general. There was this kind of charged energy. I felt that was especially charged because my first real interactions with him were around work and going to the calling factory, and talking about making something for me.

I remember the first time we sat down and started talking about what we liked about old guitars and this or that. It was kind of like, before I know it, we had been together for four hours, five hours. It felt like no time had passed.

He would say “I think these aren’t that great” or “This are wonderful,” something like that. Then I would offer my two cents and he would listen to me and absorb what we were talking about on such a deep level that I felt very, kind of like privileged, to be in his presence, you know? It’s kind of a thing that makes you self aware, but in the good kind of self aware way. Where you’re like, “Shit, I got to really mean what I say, because this guy won’t really have it any other way.”

That was the one thing that I thought was really distinguished. We worked on this project for a while. We had many occasions like this. These long talks where we’re sort of going back and forth, back and forth. I remember one of the most endearing, charming things was when Bill would actually pick up a guitar and play it himself. He’d always kind of preface it and be, “I’m not a guitar player. I don’t play much guitar.” Or he’d play something that was a silly version of a country song, but if you… After that had kind of passed and he just was there playing away, he had just the most lovely relationship to the instrument. It’s something that I always thought was really, really special. Here was a guy who built an empire. Who created guitars and mandolins that were just to the highest level. But when you saw him in his private moments with instruments himself, I think he was making a guitar or instrument that he genuinely was inspired by.

I think across all genres, all fields, that’s a beautiful thing. It’s a beautiful thing to witness, someone really being moved by their own kind of devotion.

He was just always so sweet to me. He was just so respectful of me, in a way that was almost like avuncular—like an uncle would be. Just making sure that you’re cool and you have what you need. After we had completed the first round of [what would become the Julian Lage signature edition guitar], I was using it on the road with Critter. Bill called me personally, which was the last time I talked to him. I want to say it was six months ago? He just called to say, “We did it. Thank you so much for working with us on this.” There was just such a degree of humility. Here’s this guy who just kind of conquered the world.

He was coming to me, who is nobody. I’m just someone who plays guitar and is a big nerd, really. He was just so free of ego and so open to be like, “thanks for giving me an opportunity to see things differently.” I don’t know. I just thought, if Bill Collings can do that, then that’s my role model for life. That impacted me a lot. —Julian Lage

I first met Bill around 25 years ago, and from the beginning I was impressed with his passion for guitars and life in general. He never did anything by half measures. If he was going to build a guitar, it was going to be the best guitar in the world. If he wanted to start an honest-to-God food fight in a classy Los Angeles restaurant, he was going to start a real food fight, propriety be damned.

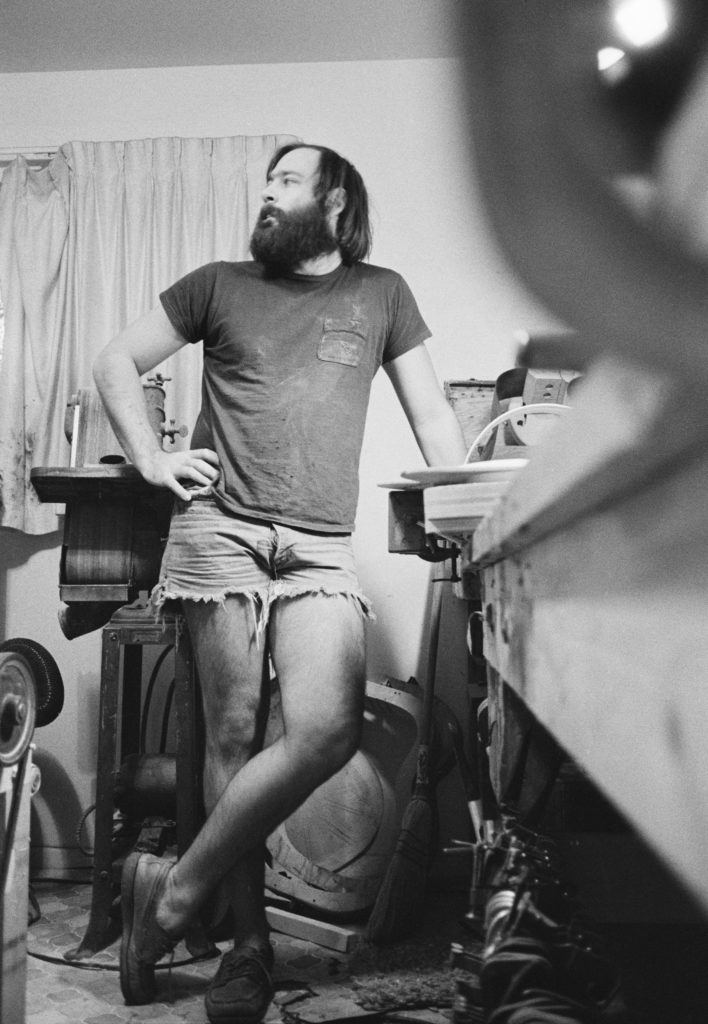

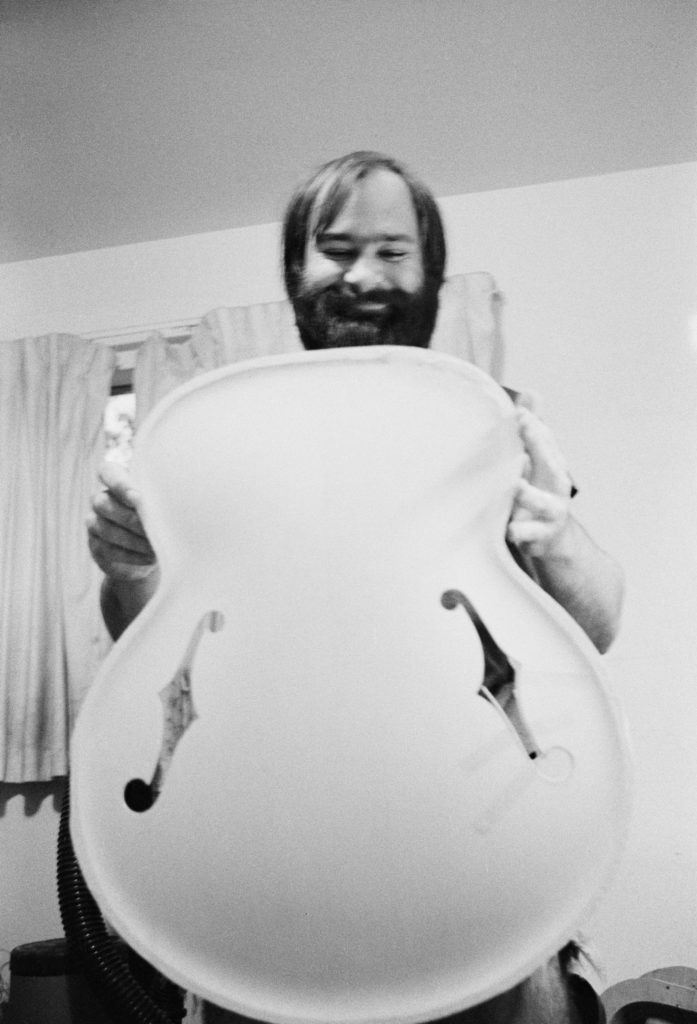

Photo by Lyle Lovett

We came to know each other over the years at various trade shows and guitar festivals. Years ago, my wife, Leanne, came with me to the NAMM Show to see what it was all about. After a few hours, she was getting burnt out on the noise and was ready to leave. We stopped by the Collings booth and Bill took one look at her, took her aside and spent the next half hour chatting with her, showing off photos of his daughter and in general not talking about guitars at all. Every time I saw him since then, he never failed to ask what Leanne was up to and he was genuinely interested in the answer.

The last time I saw him in person was at the Fretboard Journal’s Fretboard Summit a couple of years ago. He stopped by Gryphon Stringed Instruments on the way to the airport to hang out for a couple of hours. We had an exceptional 1938 Martin D-28 in stock and he spent an hour poking and prodding it and making every possible measurement to try and figure why it sounded so good. If ever there was a guy who could slow down, take a step back and say, “I did what I set out to do,” it was Bill Collings. But even with decades of having crafted some of the finest guitars, mandolins and ukuleles ever built behind him, he was still looking for ways to make them even better.

I’ve been fortunate to have owned a handful of Collings over the years, but I’m particularly happy to have these two. I wanted a matched mandolin/guitar pair that were finished in varnish rather than lacquer. Bill was a little hesitant to take the order because he didn’t have the time to make archtop guitars at the time. But when he heard the mandolin was for Leanne, he relented. We had to wait almost three years to get them, but when they finally arrived, they exceeded even our high expectations. Goodbye, Bill. You made the world a more musical place, which, to me, is just about the finest legacy a man can leave. —Michael John Simmons

What Michael [Simmons] didn’t mention [above] is how Bill prepared us for the food fight that evening by filling his hand with raw anchovies and then shaking hands with the soon-to-be combatants, or lightly patting their cheeks or (my favorite) tousling their hair, leaving behind the unmistakable proof of an anchovy encounter.

I met Bill first as an exhibitor at a Charley’s Guitars vintage show in the ’80s in Dallas. He had a booth with just one exquisite carved archtop that he had built, and fascinating as it was, we talked guitar several times over the weekend. He was not a man shy about expressing his opinion, which was usually backed up by solid, reasoned thinking (or a handful of anchovies). There was only one of him and I’ll miss him a lot. –Joe Mack

In 1991, I was working for a consulting firm that sent teams of us out of Boston to inspection sites all over the country. We conducted asbestos inspection for litigation purposes—primarily for product identification so that the litigation and settlement costs would be charged to the appropriate manufacturer. We were going to travel to Dallas, and I had been flirting with the idea of buying a real nice guitar, and I was being lured by an advertisement in Frets for a special Clarence White guitar model. The ad, if I recall correctly, was just about one half step above a classified ad. It had a sketch of a guitar and a head of steer on it. Not only could you buy a guitar, but you could also order genuine bullhorn guitar picks from the same place.

It ddn’t matter to me that I didn’t know who Clarence White was or why a guitar was named after him. I was single, worked lots of overtime, all expenses were covered and I wanted to treat myself to something special— and this seemed like it. I called the number on the ad and set up an appointment during my Dallas work trip. I wish I could remember the man’s name. I went to his house or apartment, two chairs were set up in the middle of all these guitar cases. We sat down and he said, “Why don’t you try this one?” I started to play and it was immediately otherworldly. I think I exclaimed, “Holy shit!” I hope not, but I remember thinking it. He deadpanned, “You like it?”

“Oh my God, yes!” I hope that everyone that has ever played guitar has a moment just like that: the time when you have played the best guitar you’ve ever known. We played a couple of others, but it was as if I had been drugged. I had never heard such a sound out of a guitar before—the bell-tone clarity and focus. It was magical. I asked the price: $4,800. I had money, but I didn’t have that kind of money. I played a few others in my price range—and bar none, they were all far and away better than what I was playing—but I couldn’t bring myself to pay that kind of money for something that didn’t, to me, measure up to the first guitar I played. I had resigned myself to the fact that I would not buy that first guitar, but I was thankful that I got to experience it.

We chatted for a while and I asked him about who made them. He said, “Bill Collings down in Austin. I came up with the idea and sell them, but he built them for me.”

As fortune would have it, we were going to Austin in the next couple of weeks, so I thought, “Why not?” (Turned out it was my very last trip for the company.) I called Bill when I was in Austin and asked to meet him and talk about a guit ar. I told him about my Clarence White experience on the phone and he said something to the effect, “You didn’t buy it. You’re the first guy I know of that ever walked away from him.” I wasn’t sure that this was a good or a bad thing, but we were to meet at the shop the next morning. I imagine at that time he didn’t get too many requests for shop tours and interviews, so he may have been as curious about me as I was about him.

ar. I told him about my Clarence White experience on the phone and he said something to the effect, “You didn’t buy it. You’re the first guy I know of that ever walked away from him.” I wasn’t sure that this was a good or a bad thing, but we were to meet at the shop the next morning. I imagine at that time he didn’t get too many requests for shop tours and interviews, so he may have been as curious about me as I was about him.

When I got there, I was let in by one of his guys and we chatted for about 30 minutes or so. He was working on a neck, and then Bill came in and we started talking guitars. Mostly about sound and sound qualities. He’d pick a guitar and ask, “What does this sound like to you?” The another: “How about this one?” We went through a couple of dreadnoughts, and then I looked up and on the wall saw my first nondreadnought guitars. I didn’t know such instruments existed. I may have said, “Wow, look at that one, what’s that sound like?” It was an OM. I played it and it had “it.” Bill said, “It sounds airy to me. Is that what you are looking for?” I agreed and I asked, hopefully not rudely, “Can I play that cool one over there?” It was a C10 Deluxe and I fell for the headstock and all the proportions—the full meal deal. It was a C10 Deluxe that I wanted.

Bill said, “I think I can do it,” and we chatted about what dealer I would make the purchase from. I told him that I was moving to Seattle, and he said that I should contact Dusty Strings because they were a new dealer. We chatted some more and I asked a general question about “How do you do this? Make these great instruments?”

He gathered himself and focused a bit off in the distance and he said, “What we [makers] do is build wooden boxes, and what I have figured out is how to make a really good wooden box.” I thanked him for his time and generosity.

I drove out from Boston to Seattle on New Year’s Day 1992 and took a more southern route, feeling that I-90 was too far north and snowy. I crossed most of the country along I-80 and dropped a little south to Lawrence, Kansas. I had seen an ad in Frets of a guitar shop in Lawrence that carried Collings guitars [Mass Street Music], and thought that I should take a look. The person that helped me brought a lot of instruments, but in particular on OM that had it. He said, “If you like that, watch this.” He went into an open tuning and the otherworldly thing happened again. It affirmed for me that I was doing the right thing having Bill build me a guitar.

In Seattle, I contacted Barry Hunn at Dusty Strings and told him my story, and we both waited. If I recall correctly, Bill called me to say that the guitar he was building for me was still a couple of months out, but he strung up another instrument and he thought that it had what I was looking for. “I build them for medium gauge strings but the top on this guitar…I don’t think it is strong enough for medium strings. I think that they will overpower the top. It works well with light strings and I think it has the sound quality you want.” He let me know that he could ship to Dusty Strings and I could try it out. If I didn’t like it, he’d ship the other guitar when it was ready.” I thought if Bill thought it was the one for me, I should respect his opinion and give it a try.

When I went to give it a test drive at Dusty Strings, it was a crazy Friday late afternoon. For whatever reason, the store (it was smaller than it is now) was extremely busy. There were private lessons, group lessons, people strumming guitars, the clutter and anxiety in my head—and even in the practice room, I couldn’t “hear” the guitar. I was very bummed out. I knew that I would have to play it at my apartment to hear it, but I also knew that I would have to pay for it. “Could I return it if I don’t like it?” Barry had an unforgettable and indescribable look on his face; it was perhaps as tortured as mine.

I took it home, had a bite to eat and something to drink. I opened the case and looked at the guitar and it looked back at me. I picked it up and turned off the lights so I could focus on the sound. It was it for me. I played it almost until the sun came up. I called Barry the next day when the shopped opened and apologized for not recognizing it was it at the store.

I later wrote Bill a thank-you card. He probably received thousands between then and now. What sticks with me was his wooden box reference. I’ve never heard anyone else speak of them that way. The man had a way with wooden boxes.

I still have the guitar. —Larry Lee

I met Bill with Lyle Lovett in 1978. We were really friends and hung out a lot together in the ’80s. All that time, I had had two or three guitars, but I didn’t even think about buying one of Bill’s guitars because in the first place, they were kind of expensive, and in the second place, I kind of thought what I had was enough.

Somewhere around ’92, I brought Bill a guitar that I’d been playing for a long time, and he said, “This is the last time I’m going to fix this one up.” We were pals. I’m like, “What are you talking about?” He said, “I’m not going to fix your stuff anymore. You’re not going to keep bringing it to me and having me fix this old junk that you play.” By that time, he had gotten extremely cocky about what he did. I said, “Well, what am I supposed to do?” He said, “’You’re supposed to buy a guitar from me.” And so I asked, “Well, what should I have?” He said, “Well, I think the perfect guitar for you is this C10 model that I’ve been working on.”

Over a lot of going back and forth about the wood and then just the specs and everything, I wanted a wider neck than other people did, because I like wide-neck steel-string guitars. He made this guitar and he had Tom Ellis’ 8-year-old daughter cut the inlay for the guitar because on the top of it, it has this bass which is reflective of the song of mine, “The “Five Pound Bass.” It has this beautiful fish on it and it’s just “Collings” across the top of it. It is such an incredibly great guitar. It is so beautiful, it sounds so great. And he was true to his word: Any time I ever had problems with any of my guitars—now I have probably 10, maybe 15 Collings instruments—it’s no problem.

Before that, I once went to his shop when he was over on Red River and he was by himself at this time, in this little garage kind of thing. He was doing a lot of repairs and he was making some guitars, but I was not paying attention [to those], I just wanted to make sure my stuff was okay, which was just a couple of Martins.

I went over there and he did this classic Bill kind of thing, he spoke really quickly. And he goes, “Hey, you like Martins, don’t you?” I go, “Yeah, I like Martins.” “Would you like a Martin?” he said. I said, “I don’t know, let me see it.” He goes, “It’s right here.” It’s a 1946 0-18. I said, “Yeah, but how much do you want for it?” He goes, “Four hundred dollars.” I said, “Okay…” He goes, “Three seventy-five?” I said “Well, does the case come with it, so I can take it right now?” He said, “I’ll give it to you for 300!” I gave him the $300. That is why he has Steve McCreary running that shop—because he was such a generous guy. He’d give it all away. —Robert Earl Keen

The stone-cold finality of Bill’s passing caused a failure of comprehension for me. If a guy who bucked every convention, and seemed to dodge all consequences, could die, what chance did the rest of us have?

Bill was pretty content to do it his way, and did it all himself until about 1989, when Santa Cruz Guitars showed up at Guitar Resurrection in Austin.

Photo by Lyle Lovett

Bill was staying at my house after a CNC immersion at FADAL and was really anxious over his commitment to speak at the upcoming American Stringed Instrument Artisans convention in C.F. Martin’s neighborhood. SCGC had just completed our 13th year in business, but Bill had hired his first helpers only recently and hadn’t suffered any public speaking yet.

He thought it would be a great idea if we did the talk together, and to soften the pitch, he made an unusual confession. Bill said that I was the one that caused him to hire his first employees. The rest of the story, he said, was that when he walked into Jim Lehman’s store and asked Jim what were those new guitars? Lehman told him that they were handmade guitars from Santa Cruz, California. Bill said his vision literally went red with rage that we had come to his town with our damn guitars, and he swore on the spot that he would start a company to kick our asses and run us out of business. Bill and I were closer after that.

Some things came easier for Bill than they did for others. He was gifted with a quick and brilliant mechanical mind, and with that a natural ability to capture classic proportions and design elements. These God-given advantages, along with his spooky good craftsmanship, produced guitars that looked really expensive, worked very well and sounded explosive.

Bill’s timing was sweet…and his method calculated. The buyers of expensive acoustic guitars had come of age under the German propriety of C.F. Martin & Co.’s traditional class act. Martin’s iconic appropriateness was begging the challenge of a populist prankster of undeniable talent that could out-Martin Martin when it came to making guitars.

Bill shared much of the same demographic as these new buyers and was prepared not only to exceed their expectations in the guitar but to cater to their baser needs: the thrill of acquisition. What better way to enhance this than to make it hard to get, heighten the anticipation by making them wait and nurturing the deliciously dangerous threat that if you tried to push things, you may suffer a spanking from Bill himself!

I didn’t know Bill as a dad or husband or co-worker, though I can’t imagine him having any lack of success in these efforts. I knew him wholly in the context of guitarmaking. Our public personas were comparable to Muhammad Ali and Howard Cosell: Bluff and bluster and mock derision were countered by nonpublic acknowledgements and co-operation between us. Privately, we shared a respect for each other and mutual appreciation for how we both beat the odds against success in the making of genuinely superior guitars.

In later years, we both got busy and defaulted more to the roles our market had assigned us to. A hallmark of our tribe is being open source for each other: Some of us make sure that others know they are welcome to our expertise. Bill had an important image to manage, though he continued to reciprocate by safely translating through his trusted teammates.

Whatever effect that Bill had on any particular one of us, his body of work and influence will continue to bring a lifetime of joy to generations to come. One of Bill’s great assets is Steve McCreary, whose rock solid “hand on the tiller” management of the company will assure the best possible continuity of Bill’s legacy and his relentless attention to detail.

As long as acoustic guitars are played, Bill’s masterful influence will be present. The high standards set by Collings guitars will remain as an elusive goal of future factories and individual luthiers alike. I have personally learned some valuable life lessons because of that guy, and try as I ever may to do this on my own, Maestro Collings’ encouragement, disguised as derision, will always be in my peripheral vision. —Richard Hoover

I was already a fan, having been pointed in the right direction by Julian Lage some years previous. But when I met Bill at the Fretboard Summit in 2015, it struck me that I was in the physical presence of a genius. I was among a small choir of other Collings/Waterloo disciples, and on everyone’s face was the attentiveness you find in the presence of a master. Bill was explaining how preventing anyone from working too long on any particular task could force more greatness into the end result. I figure by then my own awe had taken over my face, too. I also remember being envious of the way Bill’s hands displayed so much character; roughed-up from so much loving and frustrating trial and error, and still having a softness. I wondered how much constant contact with the surface of the craft it takes before the skin on your hands becomes like polished stone. Even the numerous nicks and cuts looked smooth and sculpted. It’s a memory of Bill’s hands that reflects this idea found in his Waterloo guitars: that details can serve the art of imperfection. Safe travels, Bill, and thanks. —Blake Mills

I worked for Bill Collings a decade or so ago, and was very fortunate to learn how to build guitars there. Collings instruments are of the utmost in quality and consistency, and that is a reflection of Bill’s dedication. I recall one weekend, I was making a soprano uke from rosewood and spruce scraps I had. Bill was nice enough to let us come up to the shop and work on our own projects on the weekends. Usually the shop was about empty, but Bill was often there.

Collings was not yet making ukuleles, but when Bill walked by, he stopped and said, “That looks good, you could probably make the kerfing thinner. You going to do shellac or varnish for finish?” He then proceeded to talk to me about how a finish affects an instrument. He talked about bracing and wood. He talked about mandolins and guitars. He saw that I wanted to make this ukulele as nice as I could and went out of his way to teach me a great deal. I was lucky to have a number of learning moments like that with Bill, as well as all of the fun and ridiculous moments. Like the time he ran around in a gorilla mask on his birthday, or the snake he lowered onto a worker from the rafters with a fishing pole.

Bill, and the amazing people he surrounded himself with, have been my biggest supporters, inspiration and motivation. Not only in my efforts to meet their expectations as an employee but in my efforts as a luthier since then, as well. I could never express how grateful I am for my time at Collings, or for those special moments with a man I admire like no other. They say you should never meet your idols, but some people become idols because we were lucky enough to know them. Bill was absolutely one of my favorite people, and he will be greatly missed by many. Fortunately, my shop is full of things that remind me of him every day, and his shop is full of people who will continue to build his instruments and cases the way he intended. Thank you, Bill Collings. —Travis Django Wade

I’ve been reminded far too many times in the past five years of the brief obituary that Miles Davis wrote for Ralph Gleason, the publisher of Rolling Stone magazine, back in 1975. I was still in high school, an avid reader of RS, and I was saddened by Ralph’s death. When a tribute came out in the next issue, I only wanted to read the one from Miles Davis, a great friend of Ralph’s and one of my favorite artists. All Miles said was, “Give me back my friend.” Made no sense to me back then, it sure does now: I think and say that driving my car to work, in my shop, waking up, every time I think of Bill Collings.

As we know, Bill was an innovator, engineer, artist, creator, he was all of those, but more than anything, to me he was a friend, the kind we don’t have enough of in this world. As I read and talk to folks about Bill, I’m saddened that in this busy world we didn’t spend more time together; when we did, life was a better place. We should have done a lot more things, but hell, at least we did some. It’s hard to fit all you want to do in your life, you have to pick and choose; I’m just glad that I met him when I did and got to spend the time we did together.

I first meet Bill Collings 25 years ago at the International Bluegrass Music Association in Owensboro, Kentucky. StewMac had just begun making Waverly tuning machines; Bill liked what we were doing and made Waverly the tuner on all their acoustic guitars. He pushed our quality to new heights: no one cares as much about the shape of the mounting screw head as Bill and his crew, we thank them all for making us a better company. Our friendship developed as the years rolled by: I made several trips to the factory in Austin and always talked about doing a side trip, we just never fit it in our busy schedules until this May.

StewMac is in southeast Ohio. Ohio University dominates the town of 22,000 residents, since the school has the same number of students as the town has residents. It wasn’t this large in 1970 when Bill entered the university as a pre-med student. Actually, I’m not really sure he entered or attended more than a few classes; his interests were motorcycles and females, and he quit after one year. In that year, he met a neighbor of mine, Steve Trout. Bill and Steve remained friends after that first year of school. Steve and I talked of going to Austin and spending a weekend with Bill—we started talking about this four years ago, got close a few times, but got urgent when we learned of Bill’s health issues.

Steve loves to fish; Bill knew this and talked with JT Van Zandt, a master angler on the Texas coast. It was up to me to set up the trip. First question from JT was what kind of fly fishing do you guys like to do? “Uh…we don’t even know how to fly fish.” Silence (unusual for JT). “Why are you doing this?” “We just want to hang out and get Bill out of Austin.” JT didn’t learn of Bill’s illness until we arrived at his boat on the morning of May 24.

Steve hadn’t seen Bill in 20 years, I hadn’t seen him for over year, we didn’t know what to expect when we drove up to the shop. There was Bill working on the big Chevy van that would take us to the coast, dry humping the door…same ol’ Bill. We drove the three hours to the coast with two old friends, reminiscing about motorcycles and girls…time moves on, but the thoughts between two minds that have shared time together stays in their last shared moment.

Now, Steve is an Ohio bobber fisherman (strike indicators, according to Steve), Bill and I fish when invited on trips, none of us had any experience fly fishing. JT sent us videos to watch; Bill and I got practice rods, Steve laughed. All a practice rod does is inflate your confidence. Standing in your backyard is easy; standing on the bow of a boat with a 20-mile-an-hour wind, glare, JT barking orders: Don’t bend your wrist…10 o’clock to 2 o’clock…rod straight… tip up… Shit, we all failed miserly. The elusive redfish didn’t have to worry about us; they could have been jumping in the boat and we couldn’t have caught them. Did it matter? Hell no, we were high school kids telling stories, enjoying the water, listening to JT’s tales, listening to Bill…cancer, fuck that. I mean, the subject was there: This wasn’t an escapist trip, we talked about what Bill was up against and it sounded somewhat positive, it did. But you know in the back of your mind it’s gonna be a fight. We all know too many people who’ve already gone down this road, but Bill was trying a new treatment, you just never know…

In the end, we didn’t catch any fish—we caught up on old times and found new ones that Steve, JT and I will have with us until we’re gone. It turned out that this was Bill’s last good weekend. When I drove us back to Austin, I could see Bill asleep in the rearview mirror, the most precious cargo I could be bringing home. I wanted to be able to take him to a place that could cure him, though we know that place doesn’t exist. What I got was three hours of watching Bill sleep as we rolled through the Texas countryside. I’ll take that memory.

Steve McCreary, Bill’s right-hand man for many years, summed it up perfectly when he said Bill was a cross between Steve Jobs and the Three Stooges: you got it all with Bill. Engineering brilliance and fart jokes all rolled into one man who moved us forward with his eccentric acts and off-the-charts craftsmanship. Because of William R. Collings and Collings Guitars, the guitar world is an extremely better place.

As a friend, Bill, you will be forever and sorely missed. —Jay Hostletter

Although I only spent a little over three years working at the Collings factory, Bill made a huge impact on me. I’m forever grateful for the time he allowed me to spend with him and the wisdom he instilled upon me. However, that came with a price: From day one Bill knew that he could get the best of me. It was this twisted gift he had, being able to sense the [weakness] and go in for the kill. As much of a genius as that man was, he was equally a tormenter. He seemed to prey on folks in the shop, figure out their breaking point and just never let up. Unfortunately for me—being a shy 20-year-old hippie kid from North Carolina fresh out of lutherie school and the first time out on my own—he saw an easy target. It wasn’t too long before he found out my greatest fear.

The following story has gained a bit of legendary status, from what I understand. But this is my take on it.

I had only been working there a little under a year, in buffing and finish within the mandolin department, when I had been given the task of buffing out my first MF5V: a beauty of a varnished F5 mandolin that retails for a little over $10,000. Needless to say, all my attention was focused on this instrument and making sure I completed it to the best of my ability. Being late summer, the shop had a tendency toward being invaded by the odd bug or two. Engulfed in my job, I felt something graze the back of my neck. Thinking it was one of these seasonal pests, I swatted it away from me. It soon tapped me again, and I continued to shoo it away, thinking little of it. Eventually, whatever was accosting me started smacking me in the back of the head. Confused and agitated, I rose up from my bench and, for some reason, held on to the mandolin I had been working on. At this point, something is fiercely flying around my noggin. In a panic, I lunged forward and tripped into my stool, throwing the $10,000 mandolin onto the concrete floor. As I scurried off to grab the mandolin on my hands and knees, I happened to look up. There, within the rafters above me, was Bill, doubled over, crying he was laughing so hard. He was holding a fishing rod with a dead copperhead attached to it. A month earlier, he had found out my ghastly fear of snakes. He had been biding his time, waiting for the right moment to pull one over on me.

Completely mortified and disgusted, I gathered myself and went home for the day. By the way, he didn’t give a rat’s ass about the mandolin. In fact, it ended up perfectly fine and even went on to be displayed at the next NAMM Show. At the time, I was living in a house with three other Collings employees. When the first one came home that evening, he called me down to tell me what had happened after I’d left. Shortly after my departure, management had called a meeting in the conference room for all available staff. Once gathered, popcorn was served and a video that had been taken of the incident was screened. Bill’s audaciousness had no bounds. I never saw the film, but I hope one day it surfaces so the whole world can see that side of Bill.

In addition to that, I had live scorpions dropped down the back of my shirt, coral snakes and wolf spiders hidden amongst my tools—not to mention countless interactions that should never reach publication. Still, with all that being said, I cannot describe how much I’m going to miss that man and how thankful I am to have had him in my life. —Christian McAdams

I still remember the first few Collings guitars I ever saw. The blend of build-quality and tasteful experimentation was like nothing I’d ever seen. One of Bill’s goals was to manufacture guitars in Austin that succeeded in the marketplace between the top individual builders and the upper end of the big labels’ custom shops.

He was making a few archtops himself back in 1991, and hand-signed the inside back surface with a pen. I went back and forth with Richard Johnston at Gryphon, and finally decided I’d buy it. In the meantime, Bill had called and asked if he could have it for his booth at NAMM. Richard said I’d have to take delivery after they got back from the show.

There was no guitar-building contest at the NAMM Show, but the Collings archtop got a spontaneous “Best of Show” and a cover picture from Guitar Player. When I got the guitar back, I decided I should go around and buy up some magazine copies for documentation. I bought nine.

I spoke with Collings on the phone at Gryphon now and then. I heard more about him from Lyle Lovett at a meet-and-greet. Lyle said that Bill built him anything he wanted, and in exchange, Lyle occasionally handled difficult customer phone calls for Bill. Yeah, really.

Bill Collings spoke at the first Fretboard Summit in Pescadero, California, a couple years ago. I got another chance to speak with him. I said I’d like to shake the hand of the man who has more of my money than anybody except my wife and I, and identified myself as the guy who bought the 17-inch” archtop that appeared on the cover of Guitar Player.

“I remember that guitar!” he said. “That cover picture was a surprise. I went out to the bookstores and newsstands and bought a bunch of copies of that issue.”

“So did I!” I said. “Um, how many did you buy?”

“I bought nine,” he said. —Harold Fethe

I was never a great client of Collings Guitars (though I’ve owned my share), but I had known Bill Collings for some 29 years, during which time he and I became good friends and fellow gearheads. I’d go down to the factory every so often from my home in Dallas and we’d talk guitars, wood and all things mechanical. He’d get so engrossed in talking that he’d sometimes forget what he was doing. Once, in the early days, he was enthusiastically explaining some nuance of his Porsche to me while he was gluing a piece on an archtop guitar. He then clamped it and kept talking. I looked at the piece and noticed in horror that it was glued on backwards! Of course, Bill being Bill, he laid into me with his usual colorful language for distracting him.

A few years later, my brother had bought a 930 Turbo Porsche in Austin and, knowing that Bill was an expert in these matters, I took it to him for his approval. He immediately dropped everything he was doing and took me for a shakedown of the car on the rural and hilly roads behind the old factory on Signal Hill. He had the car airborne on at least two occasions before he brought me back, white-knuckled and shaking, to the factory. He said something was not right with the car and recommended I take it to a Porsche specialist he knew. A few days later, the car was perfect. Expecting a bill in the thousands, I was told that Bill had taken care of all costs and I did not owe anything. This was just one of many, many examples of his genuineness and extreme generosity. I have taken many well-known guitarists to his shop, and he frequently took us to lunch, and on one occasion even put us up in a fine hotel, all on his dime. The culture of excellence and friendliness he instilled at the factory is reinforced by manager Steve McCreary, Bruce “Almighty” Van Wart (the wood guru), and the rest of the great staff. Bill was an incredibly unique, genuine, funny and brilliant American. The world is a poorer place for not having him here. —Jeff Khan

I remember when I first started hearing about those guitars was quite a while ago. I saw something where Joni Mitchell had one—she was talking about the guitar and that brought my attention to it. And then the first one I got to play that blew my mind was when I first met Danny Barnes, when he moved to Seattle. He had a herringbone dreadnought one and it was like, holy shit.

What really flipped me out and what was so inspiring was that there are these individuals who make these unbelievable instruments, but at the factory, you go in there and every single person in that place is like, their whole life is on the line with every little thing they’re doing. The guy making the knobs…it’s not just like he’s stamping them out. It’s like they care about every little piece of the guitar. They really raised the bar.

In this day and age, to see a group of people cooperating and working together like that—it was so inspiring. They care about every single one that comes out of there. And Bill had this crazy, obsessive vibe hovering over everything. —Bill Frisell

Bill enjoyed telling whoppers and watching folks’ reactions. At a NAMM Show in the early ’90s, I heard him spin a yarn about working up to the last minute on one of his show guitars. “We sprayed the lacquer just two nights ago,” he explained. How, his listener wondered, was it possible to buff such fresh finish? “On the flight out here, Steve, Bruce and I sat in the same row and took turns buffing the guitar by hand.” You must have glued the bridge and set the guitar up, then, in your hotel room? “Oh, we did that back at the shop.” So how were you able to buff so cleanly right up to the bridge? Bill looks his questioner in the eye, and with perfect poker face declared, “My guys are good.” —Dana Bourgeois

I am the proud owner of a beautiful Collings D2H. It’s simply a beautiful instrument: beautiful-sounding, beautiful to look at. I visited the Collings Guitar factory in Austin in 2007; tours were not provided on the day we arrived, but a Collings staff member graciously provided my wife, my daughter and myself a mini tour. Bill Collings was actually working at one of the benches. He was trying to get the top of a new model seated on the body of the guitar. My daughter took a picture of Bill as he was working strapping the top down. We moved to another area of the tour as a yell of wahoo was sent across the building, to which the Collings staff member said, “I think Bill finally got that guitar top to stay down, he’s been at it all morning.”

I was saddened by the passing of Bill Collings, I loved his vision of making “things,” his love for making guitars. I loved to listen to Bill talk about what inspired him about making guitars, cases and more. He had great passion for the art of guitarmaking, he will be missed. —Tim Ryan

I flew to Austin and did a cover story on Collings for Bluegrass Unlimited, and also spent time with Bill in other settings. One story that comes immediately to mind is watching him ruin not one, but two $600 archtop guitar tops as he was programming the laser cutter Collings uses to cut f-holes. He meticulously set one top up on the machine with his usual precision and attention to detail, programmed in where he wanted the holes cut, watched the laser create some very expensive Adirondack spruce smoke, and then looked puzzled as he realized the f-holes were in the wrong place on the top. He took that one out, then methodically replaced it, reprogrammed the cutter and the same thing happened. He was convinced it was the machine’s fault, not his!

I was also there when he was just starting to tinker with varnish finishes on his mandolin. But being Bill Collings, he had to test for himself whether or not there was a noticeable difference between lacquer and varnish. He’d borrowed a Nugget F5 and had a Gilchrist, so he asked me and Alex, who heads up the mandolin department, to play those instruments, plus identical Collings F-5s, one in lacquer, the other varnished. Alex and I traded mandolins and played for maybe 20 minutes as Bill sat with his back to us trying to hear which mandolin was which. He eventually decided the varnished model did sound better and added that to his options. —David McCarty

Probably one of the earliest stories I have with Bill was at the NAMM Show. That was when Ken Parker was first exhibiting the Fly guitar. Ken always wore glasses with a loupe on them. Bill and I got together and Bill wound up picking up a pair of glasses with about 10 loupes on them…sticking out everywhere, like spider tendrils.

Bill went up to Ken Parker’s booth, picked up a Fly and started inspecting it carefully with each different loupe. Ken Parker walked over—he was rolling on the floor laughing. He thought it was the funniest thing in the world. —Michael Gurian

Photo by Lyle Lovett

Bill once showed up at Mandolin Brothers on Staten Island to look at archtops, since he was about to start making more of them. Somehow he ignored the cornucopia of new and vintage archtops cluttering the room and made a beeline for what was my then-favorite archtop in the store: a 1980 D’Aquisto that was just the most unbelievably good example of D’Aquisto’s gift, which to my mind had blossomed to its most beautiful sound during those years.

This one still had plastic binding, but already had the enlarged S-shaped holes. Bill was holding the guitar close to him, plucking the strings quietly while the soundhole was facing his ear, his head was bent at an angle and he was muttering something to himself, completely absorbed by the guitar and oblivious of the people around him. I slowly walked up to him to hear what he was mumbling to himself…

What he was saying was, “Damn him, Damn him.” —Flip Scipio

This article originally appeared in the Fretboard Journal #40.