Nineteen thirty-five was only three weeks old but it already looked to be one of the snowiest years on record. A winter storm had come down from Canada, dumping a foot of snow on the Northeast before moving out to sea a few days later. By January 23, some businesses in eastern Pennsylvania remained closed–but not the C.F. Martin Guitar Company, where a workforce of just more than 30 men arrived for their normal shift. It was business as usual for the mostly rural folk of Nazareth, Pennsylvania.

New sales orders had arrived, and while the heating system creaked back to life and the sounds of power tools began to fill the otherwise quiet workspace, Martin’s shop foreman, John Deichman, directed his attention toward a new assignment: initiating work on a batch of 12 rosewood-bodied dreadnought guitars.

The first step was at once the simplest and the most momentous. Mahogany neck blocks had already been cut on the table saw and dovetailed on the shaper table, and now they were brought to a workstation where a set of metal hand stamps was kept: individual tools for the numerals 0 through 9, plus a dash and a few uppercase letters. Working freehand, the stamp man devoted one line to the model designations and then moved down to the next line for the serial numbers. (It was a point of some pride that C.F. Martin & Co. had been making fretted instruments for just more than a century–and their total production now numbered in the tens of thousands.) Within the hour, the neck block for the last guitar of the batch was completed:

D-28

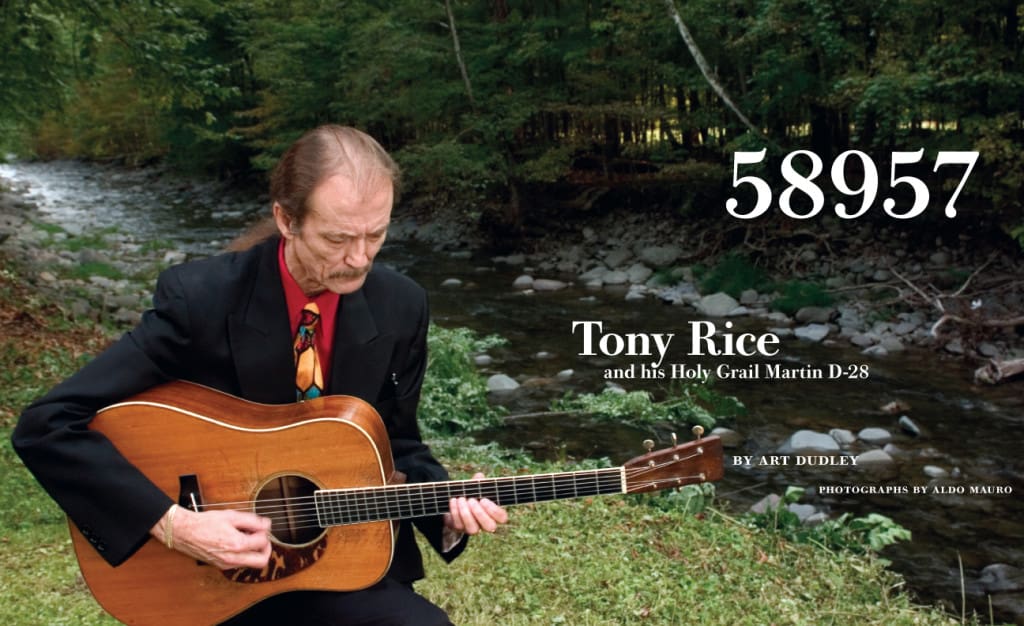

58957

Later that day, the neck block was glued and clamped to a pair of bent rosewood sides, which had been selected from the many such pieces drying in the attic of Martin’s North Street factory. The rosewood sides had been shaped on a hot bending iron, using one of the cleanest templates in the shop as a reference. The 14-fret dreadnoughts were among the newest additions to the standard Martin line, having been added to the catalog the year before.

Strips of kerfed lining were glued to the inner edges of the rims. Meanwhile, a tree-size pinwheel of clamping jigs–which, according to company lore, began life as a railroad switch before Frank Henry Martin spotted it 30 years earlier and adapted it to a higher calling–held the two-piece top and back that would be trimmed, braced and voiced with painstaking care, then glued to the rims. The body was bound and decorated with imported herringbone purfling, which was carefully taped to hold it in place, and set aside for the glue to dry.

Elsewhere in the two-story factory, work was started on other components. Necks were machined according to model – style 28 necks had diamond-shaped darts or volutes, style 18 necks didn’t, and so forth – and stacked on carts accordingly. Eventually, a Martin employee who was trained as a fitter selected one of those roughed-out style 28 dreadnought necks and mated its dovetail precisely to the body that was built around the 58957 neck block, after which he penciled the same serial number underneath its heel. The fitter pressed a steel T-bar – actually a length of sled-blade stock that might otherwise have become part of an American Flyer – into the portion of the neck that was slotted to accept it, then glued on the slotted fingerboard.

Next, a shaper clamped the neck, fingerboard side down, onto a wooden fixture and carved it: first with a drawknife, then with rough and fine rasps and finally with files and sandpaper. A whittling knife and a very sharp paring knife were used to cut the diamond. The shaping was all done using small metal templates. The first, rough template had the width of the neck at the first and 10th frets; after arriving at those dimensions, the shaper blended the neck profile carefully between the two points. Then he used other templates to create the proper heel-cap shape, the inside curvature of the neck heel, the final shape and thickness of the headstock and so forth. In all, it took about a half an hour to shape the neck and another 15 minutes to whittle the diamond.

The neck was sanded, and the fingerboard was fretted. The mahogany was filled and stained, as were the body’s Brazilian rosewood back and sides, followed by a sealer coat. Lacquering followed, along with still more fine sanding, then more lacquering and some light sanding. The neck was glued to the body, and the ebony bridge was glued down after that. Finally, a little more than two months after the shop order was written and the neck block was stamped, 58957 was strung, packed in a case and shipped out.

From there, its story is lost to us – for a while.

Intrigue, discord, rumor and even a bit of fallacy seem intertwined in the history of any great musical instrument, and so it goes with 58957, a guitar whose place in the history of American music is now, quite literally, the stuff of legend. Ask a hundred people about this one Martin guitar and you’ll get a hundred stories. One luthier claims he replaced its top and neck about 40 years ago. A merchant whose well-known shop has often been associated with the guitar now denies having sold it – or even having seen it. A musician who claims to have played 58957 says it’s an unusually quiet guitar, while another calls it a “hoss.”

Here’s what we know for sure: In 1959, the guitar was purchased from a Los Angeles music store by the young bluegrass musicians Roland and Clarence White, who were out shopping for instruments with their bandmate, Billy Ray Lathum. The boys’ father, Eric White Sr., had taken them along on earlier such trips, during which he’d bought other prewar herringbones, usually for no more than $70 each, always with the intention of fixing them up and selling them for a modest profit. (The Whites sold one such Martin to John Cohen of the New Lost City Ramblers, who kept it for a number of years.) But this time out, 15-year-old Clarence wanted a D-28 he could call his own.

Unfortunately – or fortunately, depending on how you look at these things – Roland and Clarence didn’t have much money that day and didn’t find a single D-28 they could afford at any of the dozen or so pawn shops they frequented. But there in the music store, propped in a corner alongside other pending repair jobs, was 58957. For the princely sum of $25, they bought the 1935 Martin herringbone as is.

The White brothers took the unstrung guitar home, hoping their father could bring it back to life, but the minute he cast an eye on the ratty-looking D-28, the elder White declared it a hopeless cause. Some anonymous whittler had carved the poor thing’s soundhole away to the centermost rosette rings, leaving an opening almost 4 5/8” in diameter. Its original fingerboard was missing entirely, temporarily replaced with an ebony board that was held to the neck with tape. The pickguard was peeling away from the top, and it took the boys only a short time to coax it the rest of the way off.

The next day, Roland and Clarence brought their Martin to luthier Milt Owen, who would eventually gain fame as Hollywood’s “guru of guitar repair” for his work at Barney Kessel’s shop. Owen’s prognosis was more encouraging than that of the boys’ father. Nothing could be done about the soundhole, of course, but he rooted through his parts bin and came up with a fingerboard that fit well enough: a white, plastic-bound Gretsch blank with 22 frets, the spacing of which was based on a scale almost the same as that of a Martin dreadnought. The boys were dismayed to hear that the repair would cost as much as they’d paid for the guitar itself, but they’d come too far to turn back.

A week later, they retrieved their D-28, now sporting a set of light-gauge strings and sounding very much as it should. Before they left, Owen cautioned the young pickers against using heavy-gauge strings, lest they “belly it up” and render the guitar unplayable–which is what they did anyway, of course.

Here’s something else we know for sure: During the years when he owned and used the now-modified Martin D-28, Clarence White changed the course of bluegrass guitar.

There were other guitars in the White family’s arsenal of instruments, such as the 1952 Martin D-18 that dad bought new from a Los Angeles piano store, where it had languished for almost three years. But in spite of its motley appearance–and in spite of its steadily rising string height–the herringbone was Clarence’s and, as such, it became linked in the minds of many with a caliber of playing that comes around only once in a generation, if that.

It was in 1960 when a 9-year-old bluegrass performer named Tony Rice – a recent transplant to Southern California and a guitarist in a family band, just like Clarence White – spotted the guitar backstage at a music show that was being broadcast over a local radio station.

“It was the first time I’d appeared anywhere,” Rice recalls. “I saw that old D-28, and it didn’t have a name on the headstock, so I asked, ‘What kind of a guitar is that?’ and Clarence said, ‘It’s a Martin.’ I’d never seen one like that. I thought all dreadnoughts were D-18s! So I asked, ‘Is that a D-18?’ He said, ‘No, that’s a D-28.’ I’d never heard of a D-28. The only thing I knew was that it looked like hell but it sounded like a million bucks to a 9-year-old kid!”

Clarence White let the younger boy play the herringbone for as long as he wished. “The action was so high it was almost impossible,” Rice says. There were no obvious portents, but some connection may have been forged on that day.

The White brothers and their colleagues carried on with their musical endeavors, first as the Country Boys, later as the Kentucky Colonels. Clarence’s playing with these bands was revolutionary and it set his herringbone on its way to becoming the Holy Grail of bluegrass guitars.

Ironically, as Clarence White’s reputation grew, he used the D-28 less and less often because of his growing frustration with its declining playability. The D-28’s sad condition may have led to the dumbest of all dumb-kid stunts: the day Clarence leaned the guitar against a tree outside his home and shot it with a pellet gun. The guitar bears the scar to this day.

In fact, the herringbone was rarely out of danger. After a Kentucky Colonels gig in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Clarence accidentally ran over both of his Martins while at the wheel of the group’s van. The D-18 was much worse off than the D-28 – which suffered only a side crack or two–and since the Colonels were on their way to Ann Arbor, Michigan, they brought both guitars to repairman extraordinaire Herb David, who worked day and night to put them back into service. (According to Roland White, Clarence liked the sound of the D-18 better after the mishap: “He said it had more sustain!”)

Finally, in 1965, guitarist and guitar parted company. There weren’t enough paying gigs for bluegrass bands in Southern California, and Clarence didn’t want to move, partly because he’d just gotten married and partly because of new opportunities for session players–at least session players who had electric guitars. In order to raise enough cash for a Fender Telecaster (and, hopefully, a honeymoon), Clarence used the herringbone as collateral for a loan from an acquaintance named Joe Miller.

He and the guitar would never be reunited.

By the time of Clarence White’s death in 1973, Tony Rice had begun to find his own voice as a guitarist. He worked for three years as Dan Crary’s replacement in the Bluegrass Alliance, then joined J.D. Crowe’s influential New South. It was while playing in Crowe’s band that Rice had his first chance to work alongside a former member of the Kentucky Colonels, fiddler (and bassist) Bobby Slone.

One day in 1975, Rice and Slone got to talking about Clarence White. “Bobby told me the story of why Clarence had given the herringbone up to Joe Miller,” Rice remembers. “And he started telling me more and more about Joe Miller and who he was. He used to play football for UCLA. His family owned a chain of liquor stores in Pasadena….

“And I began to think: I’d never met the guy, but Joe Miller just might be willing to let this thing go. Here’s where it gets really, really weird: I’m living in Kentucky at the time and I get on the phone and I call information for Pasadena, California, for a listing for Miller’s Liquor. And they go, ‘Yeah, we got about 20 of ‘em. Which one you want?’”

Rice rolls his eyes and laughs ruefully at the memory. “I said, ‘Give me the first one on there.’ So I called that first number and I said, ‘I’m looking for Joe Miller.’ The guy said, ‘No, Joe ain’t here now–but he’ll be back in about two hours.’ I called back and I talked to him. I said, ‘Joe, this is Tony Rice… Do you know who I am?’ He said that he did. I asked him if he had Clarence’s guitar, and he said, ‘Yes, I sure do. It’s been under my bed for nine years. Hasn’t been touched.’ I said, ‘Would you consider getting rid of it?’ He said, ‘Yeah – to you, I would.’

“This was in ’75,” Rice continues. “So here I’m thinking, Joe Miller knows what he’s got. I’m going to have to go down to a bank and talk a banker into loaning me some enormous amount of money, thousands and thousands, to get this guitar.” Sure enough, its owner insisted on having the Martin appraised by a professional before he’d name his price. Rice agreed to the plan, and the two men arranged to speak on the phone the next day.

That afternoon, Miller brought the Martin to a nearby violin shop, which, as it turned out, was also the last place Clarence had it worked on. The man at the violin shop suggested that it was worth less than one might have expected, given its present state. According to Rice, “Joe Miller called back and said, ‘I’ll take five or six hundred bucks for it.’ I said, ‘Tell you what: I’ll split the difference. I’ll give you 550.’ He said, ‘You’ve got it.’ The next day I was on a plane bound for L.A.”

A luthier friend let Rice borrow his new Mark Leaf case to carry the guitar back, and the transaction took place at LAX airport. “I kept waiting to wake up,” Rice says with a smile. “For days I was thinking, ‘It couldn’t possibly have been this easy.’”

Buying the legendary herringbone proved easier than playing it, at least at first. “It had action like a Dobro,” Rice laughs. “Although, I did a session the day I got it. It was just a coincidence. [David] Grisman was in L.A. doing a session, playing on James Taylor’s Gorilla album, on the day when I got the guitar. So Grisman came to the airport and got me and took me over to the studio. I had just picked the guitar up an hour ago!

“I opened the case and started fooling around with it, even though the action was like that,” Rice says, spreading his thumb and forefinger a half an inch apart. “And Kate and Anna McGarrigle were there, doing this album for Warner Bros. I was out in the hall of the studio, tinkering around, just diggin’ on the tone. But Grisman and the producer came out to hear me tinkerin’ around with it, and said, ‘Hey, man, we’ve got to have you on this stuff! We’ve got to have you play on a couple of these tracks!’ And I thought, ‘Well, OK, but this is the only instrument I’ve got.’ Then Grisman chimed in, ‘Hey, man, it worked for Clarence. Get in there and do it!’”

As far as anyone knows, 58957’s neck has been removed only once: by luthier Randy Wood, who did a reset soon after Tony Rice bought the guitar. As sometimes happens, the action began to creep back up within a year or two of the reset–by which time Rice was living in California and working with David Grisman. Another member of the Quintet, violinist Darol Anger, introduced Rice to Richard Hoover, Anger’s erstwhile partner (along with David Morse) in a mandolin-building venture. When he was still working as a luthier, Anger had reinforced the worn-out maple bridge plate on Rice’s herringbone with a thin ebony overlay that remains in place to this day. Among other things, Hoover performed what Rice refers to as a “tweak reset.”

The lower treble bout (and the bass bout) of 58957 feature some interesting and slightly crude repairs where herringbone was damaged and patched. Photo: Art Dudley

“Today, I wouldn’t dream of doing that without removing the neck,” Hoover says. “But at the time I did it, the body of knowledge was much more limited. In fact, at that time, there were very few people who even understood the problem, let alone how to fix it. Back then, Martin was still taking the frets out, planing the fingerboard, shaving the bridge… trying to create the geometry to get proper playability. And what I did was something I learned from violin building. The technique was called slipping the back, wherein the binding was pulled back a bit, the back was separated from the neck block and then, with a harness, you pulled the neck into the proper angle–then reglued the back onto the block, trimmed the excess and put the binding back on.

“It’s horrifying to think about this now, on such a priceless guitar,” Hoover adds with a laugh. “But at the time, it wasn’t a priceless guitar: It was a really stinky, modified old Martin! It hadn’t gained its fame-osity yet!”

In 1976, Richard Hoover co-founded the Santa Cruz Guitar Company and went on to create various incarnations of Tony Rice’s other famous guitar. (A brand new custom dreadnought is in the works, using wood from the same reserve that was tapped for the SCGC guitar Rice has used for the past seven years.) Prior to that, Hoover performed a few other repairs on 58957. “We replaced the nut, which I think is still there,” he recalls, “and there was a crack in the lower bout, on the right-hand side as you face the guitar, that I fixed for him. And we did a partial refret–which also is rarely done nowadays–and refretted, probably, the first five to seven frets.” Hoover adds that they installed the frets using the traditional hammer-in method. “A lot of my approach to repair work, even at that time, came from my training in art and museum restoration: Don’t do anything that can’t be redone later with better technology. So it’s unlikely that we would use any glue.”

In all, some of the best names in lutherie and acoustic music have been associated with the famous D-28. The bridge pins, modeled after Clarence White’s own, were made by builder Ervin Somogyi. When a new bridge was needed, the late Mike Longworth of C.F. Martin hand-selected a new old-stock blank, and the famed luthier and author Hideo Kamimoto installed it–and did a literally seamless job of filling the existing saddle slot with ebony, then cutting a new one that allowed more precise intonation. Friend and fellow musician Todd Phillips added black position markers to the white binding on the bass side of the fretboard. (Interestingly, he followed the old-time convention of putting a dot at the 10th fret, rather than the ninth.)

Harry Sparks of Cincinnati made one of the most important contributions of all, howsoever quietly. In March of 1993, Tony and Pam Rice were living in Crystal River, Florida–not just near the water but right at the water’s edge–when a tropical storm slammed into the Gulf Coast. They were awakened in the middle of the night by emergency personnel who insisted they evacuate immediately, without so much as a moment to gather up personal belongings. When the sun rose a few hours later, Rice begged a neighbor to retrieve the Martin from his flooded home.

That memory is enough to change the tone of the conversation: “Yeah. Crystal River, Florida. It was under water for at least an hour and a half, totally submerged. More like two hours. In the case. But the case wasn’t waterproof. So it was totally saturated. And it was really f***ed up. And it didn’t sound like itself for five years, at least.

“Harry Sparks came down from Cincinnati and took it under his wing. Slowly dried it out. You couldn’t just, like, stick it in an oven; you had to slowly dry it out or you’d run the risk of cracks–which did happen anyway. It cracked in several places on the back. Most of the bracing in it came loose–the back bracing.”

Rice’s mood brightens, however, when he recalls the services of luthier and friend Snuffy Smith, who lives about 45 minutes away from him in King, North Carolina. “I knew there wasn’t a damn thing that was happening to the D-28 that couldn’t be fixed,” Rice says. “And then, a few years ago, Snuffy reglued all the internal back bracing and a couple of top braces.”

Snuffy Smith, for his part, remembers how grateful Rice was to have the herringbone restored to its former glory. “He called me up after the fact,” Smith says, “and said he couldn’t play it in the basement any more: He was afraid it would crack the foundation down there! Regluing the braces really helped the volume of it.”

In the 10 years or so that Snuffy Smith has looked after the D-28, he’s completed a variety of jobs on it. He’s done a couple of fret jobs, which he glues in for stability. He leaves the fret slots sufficiently narrow so that the use of oversize fret tangs in select portions of the neck can still compress the wood enough to add back bow where desired. Smith has also reshaped Kamimoto’s original bone saddle.

The most nerve-wracking job of all came fairly recently, when Smith had to replace one of the original top braces. “There was a brace that had been cut almost in two,” he says, “at the very front of the soundhole, right under the fingerboard there. Long ago, someone put a pickup there or something, and the brace had caved in. And Tony said, ‘I’ve looked at this for 25 years and always griped about it….’

“Dick Boak at Martin sent me three braces that I could choose from. They were all old, and Tony and I picked out one that was originally going to go into a ’41 D-18. I took and chipped one little piece of the ribbon out on one side and I was able to get the old brace out that way. I lowered it on that side and I actually pulled it out of the other side where the ribbon is.

“I did it that way and got the old one out, trimmed the duplicate and left just a little bit extra in it for the bow. And when I put it back in, I was able to slide one end into the hole that it came out of and I was able to slide it up to where I’d taken that chip out.” At this, Smith laughs and sighs, more or less at the same time. “I glued it there, then I glued the chip back in, and… well, I lucked out and got the chip back in just exactly like it came out! You can’t tell it! Tony sat here for an hour with a mirror and said, ‘You could never get that out! How’d you do it?’

“Once in a while you do something like that that comes out real nice.”

Rice himself enjoys pointing out another of Snuffy Smith’s recent triumphs. If you look carefully, the tuning machine for the sixth string looks different from the others, suggesting that it was replaced at one point. Also, the finish surrounding the third string tuner indicates that it was replaced as well. “The oddball one, Snuffy and I put together as a quick fix, about four or five months ago,” Rice says. “The story with the machines is that they’re original, except for one that was on there when Clarence had it, which was a Kluson–he had a closed-back Kluson as the third string gear.

“After I got the guitar, it was still on there, and Frank Ford, out in Palo Alto, provided me a third string tuner he found as a replacement that was identical to the original. So Frank Ford put the third on. Then, about four or five months ago, the sixth string tuner–the low E–finally gave out. The worm gear and the pinion were just stripped out. Snuffy found an old Grover handle and worm gear assembly, so he constructed a new tuning gear out of parts. It kinda works!”

For his part, Snuffy Smith says that the work is never really done on a guitar such as this one: “We’re eternally doing something; it’s almost a never-ending thing…. Fortunately, Tony has had some good people work on it. That makes it a lot easier for me.”

The next project? Rice points to the tortoiseshell-colored pickguard that a fan gave him during a 1985 tour of Japan. It’s remarkably beautiful; its lines suggest movement, even when the guitar is perfectly still. “I’m going to have it taken off and re-put on,” he says. “The guy that put it on used to work for Martin. I was in Florida at the time. He did a fairly good job, but it could be better. That pickguard needs to be taken off, thinned down and put back on.”

Then Rice uses the thumb and middle finger of one hand to span the nut: “The peghead nut width, the width of the neck right here, is probably going to be changed, and reasonably soon. I’m going to have Snuffy take the binding off the next time it’s refretted, widen it with a couple of microstrips of ebony–probably about a 32nd of an inch–and put the binding back on before he puts the frets in.”

After that, Rice hands the guitar to me: “Why don’t you pick on this for a while?”

My first response to actually holding 58957 is one of surprise: How could a rosewood-bodied guitar weigh so little? My second is a brief flash of alarm–something’s come loose!–until I remember an article I’d read somewhere.

“Tony, is that the rattlesnake rattle I’m hearing?”

“Yeah,” he replies. “There should be two of ‘em in there.”

Imagine a car where the connection between the pedal under your foot and the motor under the hood is a short, straight piece of steel. It’s not that the thing goes fast all of the time–although there’s no mistaking that it has tremendous power in reserve–but rather that it responds instantly to your imagination’s every extreme.

Ever the motoring enthusiast, Rice echoes my unspoken thoughts from the next room: “It’s probably like playin’ with a Ferrari, right after driving a few Volkswagens!” he offers with a chuckle. “It’s almost like it plays itself.” Hell, yeah!

A number of people who’ve heard it up close have described the herringbone’s unusually good balance – every note in its range has equal prominence and projection. That’s true, but there’s more to it than that. With every chord or string of notes, you’re not thinking about bass or treble. It’s simply impossible to keep from being impressed, almost overwhelmed, by the rich, complex and altogether stunning tone that comes from the depths of that box.

For the most part, every Martin dreadnought is impressive in some way. But 58957 is on another plane. It’s not the loudest D-28 around–although it does have a wider dynamic range than most–nor does it have the deepest of lows or the highest of highs, but it is the most expressive. It sings with a voice that simply can’t be ignored.

It’s also very playable in its present state. To satisfy my inner dweeb, and with Rice’s approval, I took a few measurements–noting a string height of just a shade over 6/64” for the low E, measured at the 12th fret, and just over 4/64” on the high E. The neck width at the nut is only 1 5/8”, with the string slots cut surprisingly low, especially on the treble side. (It’s a testament to Snuffy Smith’s setup work that the guitar simply does not buzz–unless you really go nuts on it.) Measured from the center of the sixth-string bridge pin to that of the first, the string spread is exactly 2 1/8”–perfect for a player like Tony Rice, whose hands aren’t the least bit oversized. Hideo Kamimoto’s bridge is sized precisely to Martin specs, although its front-edge height is just a shade lower than some, at 19/64”. Another myth has it that the herringbone’s body has slightly less depth than average, but that’s not so; if anything, it’s a tad deeper than average, at both the neck block and the end block.

I ask Tony Rice, “Have you ever heard a flattop guitar that comes close to this one?” He takes a moment to reflect. “Yes,” he says, “there’s a guitar that comes very close: [Norman] Blake’s ’34. He sold it years ago to [well-known Japanese instrument collector] Mac Yasuda.”

Another long pause: “Yeah, to answer the question, there’s a couple of them. The second-favorite D-28 I’ve ever played was Blake’s ’34. And probably the third was Eric Thompson’s herringbone. It’s either a ’40 or a ’41. Those are the two that come to mind.”

Rice takes the herringbone back and says, rather softly, “It’s still here.”

“I can’t play it now,” he says. “I ain’t even warmed up yet!” But he plays anyway–with the fluidity of technique and imagination that other pickers have tried to duplicate for 30 years. He plays a phrase that spans the seventh through 12th frets: “Up here is where this guitar really sings,” he offers, before launching a series of chords and lines that morph into “Summertime.”

Ten minutes later, 58957 is back in its pretty new carbon-fiber case, the plain leather strap still attached to the pegs and laid out over the strings. Rice sighs deeply before closing the lid: “It’s a beautiful instrument. I never pick it up but that I don’t think that. It’s got to be the Holy Grail.”

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the Fretboard Journal #5. For additional stories and videos featuring vintage (and new) Martins, click here.