Guitar legend Bob Bain used to have a print-out summarizing some of the many sessions he appeared on. He’d present it to visitors like me, making the pilgrimage to his beachfront Oxnard, California home, eager to meet a man who helped shape American popular music.

The list on that coffee table went on and on… a who’s who of jazz, pop and rock greats along with some of the most acclaimed soundtracks ever recorded: Ella Fitzgerald, Nat “King” Cole, Buddy Rich, Rosemary Clooney, Sinatra, Elvis, Bonanza, Peter Gunn…

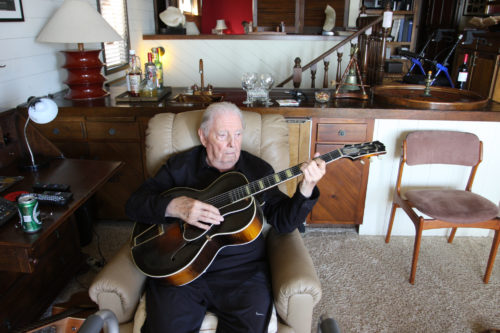

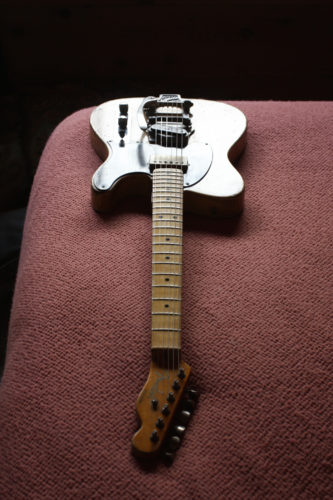

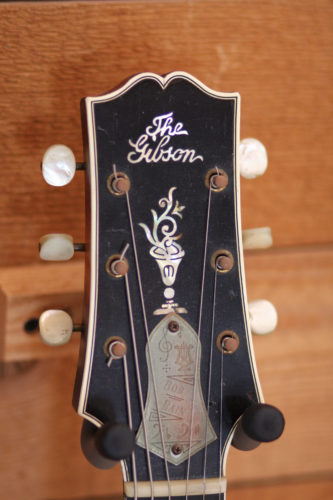

Bain connected all these pivotal dots. And he had stories to tell. He kept the instruments that mattered from way back when – the Gibson L-5 that appeared on so many sessions, the Bigsby’d Telecaster he used on Peter Gunn and alongside Doc Severinsen on The Tonight Show – and, most importantly, he just kept playing. For nearly 80 years, he was a working musician, whether that meant being in Tommy Dorsey’s big band, bringing Henry Mancini (who Bob would always reference as “Hank”) scores to life or just playing monthly jazz gigs at his favorite Southern California restaurants, as he did well into his 90s.

Bob passed away at the age of 94 this week. Over the years, we were lucky enough to make that pilgrimage to Oxnard a few times. What follows is Adam Levy’s portrait of Bain from the Fretboard Journal #36, along with all of the videos we were able to film with Bob (and friends) over the last decade and some photos of Bob and his gear taken by Kevin Kinnear. –Jason Verlinde

Gunn Slinger: True recording-studio tales from Bob Bain

By Adam Levy

My grandfather was a musical arranger who worked in television throughout the 1960s and ’70s. He used to take me to work with him sometimes when I was a kid and just getting into music. It was a thrill, to say the least. These were my first opportunities to see professional musicians at work, and the guys were so good. At a few of the sessions I witnessed, there’d be two or even three guitarists on the job. The guys would be deadly serious whenever the red light was on, then crack each other up between takes. Their camaraderie was palpable. “This,” I remember saying to myself, “has got to be the best job in the whole world.”

I still think so, though the business has changed dramatically since then. The halcyon days of tracking live with a roomful of players seem to be all but gone, and many once-busy professional studios have shut their doors for good. A recording session for a guitarist in 2014 may be as modest as an overdub assignment via a buddy’s living-room ProTools rig, or even the player’s own home setup if they have the gear and the know-how. Work is work, but low-budget sessions like these are a far cry from the way things were for a few golden decades between Eisenhower’s last term and Clinton’s first. That’s when studio musicians thrived. There was no shortage of work for players who could read and play their parts spot-on in just one or two takes. Guitarists were jobbing steadily in live radio orchestras, on soundtracks for TV and movies, and on record dates.

If anyone knows about the glory days of studio recording, it’s guitarist Bob Bain.

Bain’s recording credits are far too numerous to mention here, but among the highlights are the themes to the Peter Gunn and Bonanza TV shows, a handful of choice Frank Sinatra cuts, Nat “King” Cole’s original recording of “Unforgettable,” and the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s, where Bain strummed the actual “Moon River” chords that Audrey Hepburn mimed to. He often worked alongside other busy guitar sessioneers such as Tommy Tedesco, Howard Roberts and Dennis Budimir. Bain also regularly played in Doc Severinsen’s band on The Tonight Show from 1972 to ’92—the last 20 years that Johnny Carson hosted. I got the chance to interview Bain earlier this year at his beachfront home in Oxnard, about an hour north of Los Angeles, and I leapt at the opportunity.

To meet Bain, you’d never guess he was born in the 1920s. He still has a sharp memory and a wit quick, and he still plays wonderfully. Throughout our conversation, Bain would pick up his early ’60s Martin 0-18 to demonstrate a musical point, or just to play a few sweet impromptu chords. At one point, he asked me if I played any jazz. I do, so the two of us wound up jamming on a few vintage tunes, including “Honeysuckle Rose” and Django Reinhardt’s “Nuages.” Bain even gave me a little lesson, showing me some interesting chord shapes for a 12-bar jazz blues and demonstrating the authentic bossa-nova rhythm pattern that he’d learned decades earlier from Brazilian guitar virtuoso Laurindo Almeida.

Bain worked his first professional gig in 1939, when he was just a teenager, playing bass with a trio in an Italian restaurant on Sunset Boulevard. (Early on, Bain was handling guitar and bass with equal gusto. The goal was to work, and he was glad to play whichever the gig required.) Bear in mind, playing guitar—professionally or otherwise—was far less common back then than it is today, and there weren’t many star players one could look to for inspiration. Guitar as a phenomenon was still 25 years off. (Many consider the Beatles’ 1964 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Showas Ground Zero for American popular culture’s fascination with the instrument. Bain was already a pro before any of the Fab Four were even born.) No, it wasn’t any guitar hero that led Bain to pick up the instrument. It was simply a chance meeting with a boarder at his family’s rooming house.

“I was living with my grandmother at the time,” Bain says. “She had one tenant who was a guitar teacher. I used to hear him practice, and I got to know him. He had an acoustic guitar—a Kalamazoo—and he showed me some chords. I liked that immediately.” Not long after, Bain took some lessons with Russ Stout, who was a banjo player with the Coon-Sanders Orchestra. “He was a marvelous player,” says Bain. “He’d switched from banjo to guitar. Some of the guys back then were switching to tenor guitar, because it was tuned in fifths like a tenor banjo. That’s what Eddie Condon did. Switching from banjo to [standard] guitar meant that you had to learn different fingerings altogether.”

One of Bain’s first big breaks as a player was a steady gig with bandleader Tommy Dorsey. This was in the early 1940s, at the height of the big-band era. He played on “Opus No. 1,” one of Dorsey’s biggest hits. Bain was more felt than heard with the band, however. “Rhythm,” he says, “that’s all it was.” Bain played a 1939 Gibson ES-150 on the gig, equipped with a bar-style “Charlie Christian” pickup. He played the ES-150 acoustically, as Dorsey had no interest in amplification. That guitar had been a gift, in 1940, from Joe Wolverton—a fellow guitarist and mentor. “Joe told me, ‘I think you should have an electric guitar.’” Bain left Dorsey’s band after a few years and looked for more work at home in Los Angeles, but the studio scene was slow going at the time. “As Sweets used to say,” says Bain, referring to jazz trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison, “it’s hard to be melodic when work is so spasmodic.’” Bain was able to drum up some nightclub gigs, but he was soon offered a touring gig with Bob Crosby’s band and he took it, just to keep working regularly.

At the end of 1946, after about a year on the road with Crosby, Bain came back to town and again went looking for studio gigs. This is when things finally began to happen for him. “I worked at NBC a lot,” he says. “I had my own group there for a while. We played what were then called ‘sustaining shows.’ There were no commercials—it was just music. You’d have a girl singer and a quartet or quintet, and you’d play for half an hour. NBC had the Red Network and the Blue Network back then. The Red Network was commercial. The Blue had no commercials. It was a public service, like PBS. Then I went to MGM and started to work there, and then worked at Fox a lot. By that time, all the radio shows had begun using guitar and that’s where all the guitar players were. You know, you couldn’t find a guitar player sometimes. You’d call 15 guys and they were all working!”

By the early 1950s, many top bandleaders and orchestrators were favoring electric guitar as the hot new sound—in part due to the popularity of hit records by Les Paul. Prior to that, Hollywood arrangers had thought of the guitar as a solo instrument for Spanish-style classical music, or as a rhythm instrument for jazz and swing. Bain says that it took some time before anyone in town really knew how to write for the electric.

“I remember that [film composer Dimitri] Tiomkin had asked his orchestra who was playing on that hit record he’d heard. It was Les Paul. Tiomkin said, ‘Can we get that sound?’ This was for a John Wayne picture that Tiomkin had written the score for. But when I got to MGM for the session, the orchestrator told me, ‘We didn’t write any guitar parts. It’s all piano parts. Just come in when you think it’s right.’” Bain set up next to the French horn player on the session, Vince De Rosa. “He and I were pals,” Bain says, “so I thought I’ll just sit here and come in when Vince comes in. His part was written into the piano part, already transposed, so I could look at it and read it just like a guitar part, in the right register. Tiomkin thought it was just great! At the end of the session, he looked at me and said [mimicking Tiomkin’s Russian-Jewish accent], ‘Mein boychik, you give me good record sound.’”

Of course, it wasn’t just Bain’s sound or his reading chops that kept him in high demand. It was also his temperament. As orchestrators were often stabbing in the dark when scoring guitar parts, some of the things they wrote were unplayable—or nearly so. Rather than making a big deal of the problem parts, Bain was always more tactful. “If the part is impossible to play,” he says, “there’s no reason to try to play it. You go to the composer and say, ‘I can play something likethis,’ and that will be fine. Don’t try to play it, then make him look bad and yourself look bad. You have to learn to not be afraid, say, ‘I can’t play this.’ It takes experience to learn to do that. With some leaders, you learn that they don’t mean for you to play what they’ve written literally. They’re showing you what they’d play on piano, and you figure it out on guitar yourself. But you have to know the leader. You have to have the experience of knowing what he wants and get used to knowing what they mean.”

“Now, a guy like Hank,” Bain continues, “he would never do that.” Bain is talking about Henry Mancini, one of the composers who wrote lots of electric guitar into his film and television scores in the late 1950s and early ’60s, and who hired Bain whenever possible. Mancini, the guitarist says, always knew exactly what he wanted. Over time, as these two got to know each other better, the composer would sometimes use shorthand to convey the sound or feeling of what he wanted. To illustrate this point, Bain tells the story of one particular session where Mancini trusted him to play the right thing with only minimal ink on the page to indicate direction. “We were recording ‘The Second Time Around,’ which features a vocal group with the orchestra,” he says. “Hank wanted to get the feeling of older people. This song is not teenagers. There’s a guitar cadenza at the top and then the singers come in, so he wrote a big E-flat chord symbol with a note over it that said Eddie Lang. That could be anything. All kinds of things you could do. I played something old fashioned [Bain picks up his Martin and demonstrates] and he loved it. We were at a party not long after that, and [guitarist] Jack Marshall walked up to Hank and said, ‘Hey, that was really a beautiful thing you wrote for Bob on ‘The Second Time Around.’ Hank just smiled and said ‘Thank you.’ What else could he say?”

At times, of course, there were plenty of little black dots to be read, and Bain could handle those. But, he attests, knowing when to play the notes and when to just make music—manuscript be damned—comes down to experience. “You’ve got to know what to do at the right time,” he says. “Don’t get upset or get excited, and don’t ask too many questions. That’s a hard thing to teach younger musicians. I sent a sub in to play the Tonight Showone time, and the guy asked Doc a question about a note on one of the charts. Now, we’d been playing the chart for three years already. Doc gave him a look, like You’re gonna ask a question about a note? Figure it out for yourself. The band is playing. If you don’t like it, fix it, but don’t ask me!That’s the thing. You learn not to ask dumb questions.”

As the guitar grew in popularity throughout the 1960s, it became more common to have two or three six-stringers on recording sessions. “Pete Rugolo and Lalo Schifrin were the composers I remember that started writing for two guitars. They would use the electric within the orchestra, more like a timbre, maybe doubling a flute solo. Or like the way Frank Comstock wrote for the Les Brown band—with the guitar doubling the trumpet. You still want a rhythm player, so they’d hire two guys rather than having you play rhythm, then stop and pick up your electric guitar.” It’s worth noting here that while “rhythm guitar” is a pretty general term, when Bain mentions it—as he did many times during our conversation—he has something specific in mind. To Bain, and to many players of his generation, it means an acoustic rhythm part played on an archtop instrument, à la Freddie Greene with the Count Basie Orchestra. Bain will sometimes even use the phrase as a noun. For instance, he calls his prized 1934 Gibson L-5 his “rhythm guitar.” “We always referred to it as a ‘rhythm guitar,’” he told me. “The band leader or contractor would say, “Bring your electric, bring your rhythm, bring your gut-string.’ Some people might say ‘acoustic,’ but that could mean anything. ‘Rhythm guitar’ meant bring your Freddie Greene guitar. Early on, you could walk into a session with that and 99 percent of the time, that’s all you’d need. Electric was never asked for.”

That’s something that may be hard for modern-day players to comprehend. From the beginning of the jazz and swing era, up through the late 1940s, the guitar usually wasn’t considered a feature instrument. It was there to keep time, strumming chords on each quarter note, functioning almost as a connective tissue between the drums and the acoustic bass. Sometimes the guitars—usually archtop models—would be miked, sometimes they’d have to share the microphone with another instrument, as was the case when Bain recorded “The Minor Goes Muggin’” with Dorsey and his orchestra on a date featuring guest pianist Duke Ellington. “I sat in the crook of the piano,” Bain recalls. “In those days, sometimes they picked up the rhythm guitar on the piano line, because they only had so many inputs for the board. They’d have a mic on the drums—one mic, that’s it. There’d be mic on the bass, or maybe they’d put the bass and drums on the same mic. Sometimes they’d put the bass, guitar, and the drums all on the same mic and have the piano alone. But for some reason this guy [the engineer] wanted me to play to this piano mic, in the crook, facing into the piano. Duke kept smiling. He was so relaxed, even though they were playing tunes he didn’t know.”

Still intrigued by the image of studio guitarists working in tandem, I asked Bain how the pecking order was decided on such sessions. In other words, who’d play the Guitar 1 book, who’d play Guitar 2, and so on. “It would usually depend on the leader,” he says. “If it was Billy May, Al Hendrickson would play first guitar, because Al worked with Billy all the time. If it was Hank, of course I’d play first. For instance, I used to do a show with Howard [Roberts], and I was the first guitar player. Stanley Wilson was the leader. But if there was a guitar solo written in the first part, I’d automatically open the book and tell Howard, ‘This is your part.’ Stanley loved the way he played too.” However, Roberts—ever the tinkerer—didn’t always have his full attention on the music at hand, according to Bain. “Howard would always be sitting there with his mind running, like, How can I change this tailpiece to make this guitar sound better? He had all these prototypes that Gibson was making for him at the time. So if we had three or four cues in a row with no guitar parts, he’d find the nearest phone booth and be making calls.” If Roberts was still gone when it was time to play again, Bain would try to find a way to play both parts on his own. When Roberts returned, he’d ask Bain, “Did I miss anything?” Bain says, “I’d tell him, ‘No.’ Nobody knew the difference.”

Like many session players of Bain’s generation, he’s a jazz man at heart. Throughout his career, he has played lots of the music on film and TV dates, on nightclub stages, and as a sideman on records. He still likes to drop in now and then on John Pisano’s Guitar Night, a jazz-slanted concert series that happens weekly in Burbank. He also gets together with fellow studio vet Mitch Holder to play a few tunes at home, whenever their schedules align.

One of the first jazz players that piqued Bain’s interest was Gypsy-swing guitarist Django Reinhardt. Very early in Bain’s career, he had a touring job as the bassist for a Western swing trio. The group took a portable record player on the road, along with a stack of Reinhardt records. “We had all his records on Decca, maybe 15 or 20 of them. We’d listen to them in our hotel room after the job each night. Listening to Django, you couldn’t go wrong. It’s amazing how Django has become an in thing. You’re supposed to know who he is now. Back then, nobody knew who he was except guitar players.”

Bain spoke of Reinhardt with such enthusiasm, I was curious to know whether he had ever tried to learn any of the master’s work, note for note. “Yeah,” he says. “It’s fun to try to duplicate Django, and now there’s so many fellas that do it very well. But I don’t care who it is, you can pick Django right out. There’s Django, and then there’s somebody that sounds like Django. It’s like I can pick out Wes Montgomery. I don’t think anybody can sound exactly like him. There’s just something that’s not there with the other players. His sound, the way he phrased things, and the ease with which he played those phrases—you know, playing in octaves. I did a lot of sessions for Time Life records where we’d have to duplicate old original recordings. One was Wes’ version of ‘Tequila.’ That was an easy one to do. But there was another one that I did that was amazingly hard. I had to do it maybe five or six times to get it right. Still, when I listened back to it, it’s not Wes. It’s not even close to getting his sound the way he did. He had that sound. And that’s what I think about Django.”

“There’s something in your fingers,” Bain continues, “or it’s in—well, I don’t think it’s the guitar. Because Django sounded good on any guitar. He didn’t have to have that one Selmer. Barney [Kessel, famed jazz guitarist] told me about one time on a recording date when Django came in without a guitar. His had been stolen. Somebody in the studio knew somebody nearby, and they borrowed another guitar for the session. It wasn’t anything like Django’s guitar, but he sounded the same! He didn’t say anything about that guitar not being like his. He just played. Incredible talent. I think it’s in the way you feel the strings. To be able to feel that on electric guitar, that’s tougher. But Django on those electric guitar records, those few solos, it’s amazing how he was able to adapt. It didn’t seem to hang him up at all.”

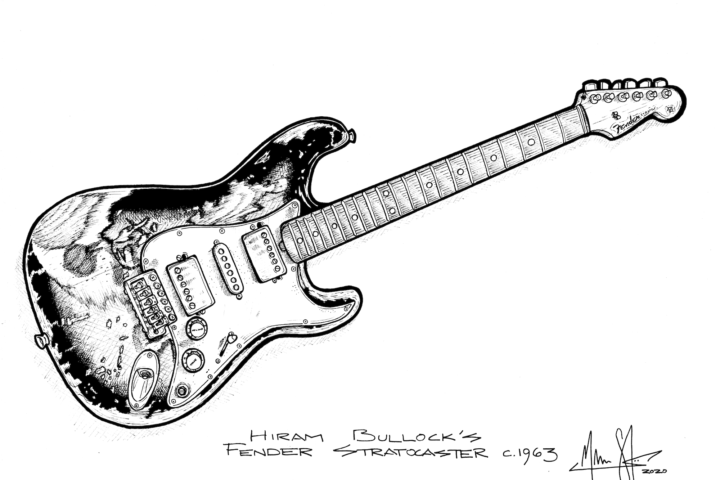

At this point in the conversation, Bain and I had been chatting for a couple of hours, covering several decades of his personal and professional history. Bain was a charming host, offering elephant-ear cookies and Dr. Pepper when we took a short midinterview break, but I didn’t want to take up his whole afternoon with my questions. Still, I had a few more things I wanted to talk about with him—like his 1953 Telecaster. That’s the guitar played on Mancini’s Peter Gunntheme, as well as on countless sessions of all kinds. I’m glad I asked. Bain told me how the storied Tele came to be his main axe. It wasn’t his first electric guitar, as it turns out.

“Les [Paul, Bain’s dear friend] told me to get a Les Paul guitar. This was in the late ’50s. He said Tiny Timbrell [guitarist and West Coast sales rep for Gibson at the time] had a good one for sale at [Wallich’s] Music City [a well-known Hollywood record store that also sold instruments]. I went and got that guitar, and used and loved it. Then something happened where even the band leaders got to know the name Fender. So you’d get a call from a contractor and they’d ask, ‘Do you have a Fender?’ That was the rock-and-roll sound they were looking for. I went back to Music City and traded my Les Paul for this ’53 Telecaster. I thought it was okay, but there was so much highs in the sound. I asked Tiny what could be done, and he said, ‘I have an idea.’ He took the guitar and put a humbucker up by the neck. He had to put a shim under the neck to lift it up, because the strings would hit the humbucker. Tiny set it up so it was perfectly in tune. I used that guitar on everything since then.”

Bain was happy to let me play this amazing piece of musical history. I can vouch for the fact that it still plays perfectly in tune. I was a little surprised to find that Bain’s choice of strings weren’t particularly heavy. I’d presumed that players of his generation preferred the heaviest strings they could lay their hands on. Bain tells me that Barney Kessel—who he knew well, and often worked with—would use a .013 or .014 for his high string. “I couldn’t hardly push it down,” says Bain. “I used thinner gauge, but it’s a matter of choice with strings.” Another surprise to me—the strings on Bain’s instruments weren’t flat-wound. I’ve long thought that flats were a key part of the electric guitar sound of the ’50s and ’60s. Bain shakes his head. “Flat-wounds are great, and of course the string noise is a lot less. But I didn’t think flat-wounds punched out as nice. I always liked regular strings, and I was one of the few guys that used an unwound third string.”

While on the topic of strings, Bain tells me that he changed his at least once a week during his busiest years. “That,” he says, “is something that Les would always say. ‘Younger guitar players coming up, they don’t realize how important it is to change strings.’ They just lose something after you’ve played them for a week. Howard [Roberts] would sometimes change strings on a 10-minute break or at intermission because he felt they’d already lost something. I wasn’t that kind of a person. In fact, on certain instruments—like my Danelectro six-string bass guitar—the older they were, the better it sounded to me.” It wasn’t uncommon, Bain says, to be asked to play that Dano along with the actual bass part on a recording session, adding a timbre that neither the guitar nor the bass could render alone. On the original theme from the Mission Impossible TV show, for example, Bain played six-string bass guitar along with Carol Kaye’s propulsive bass line. “That put a little edge on it,” he says.

It was finally time for me to go. Before saying goodbye to Bain, I ran the list of questions I’d wanted to ask through my mind one last time. Yes—there was one more thing I wanted to know. I hadn’t looked up Bain’s exact age prior to our interview, though I knew he had a lot of history behind him. I figured it was fair to ask, and he answered without hesitation. “Ninety,” he says, eyes glinting. “That’s a lot of years of C7.”