The Backstory

In Ivory’s Ghosts: The White Gold of History and the Fate of Elephants, author John Frederick Walker notes that by the 19th century ivory had become “the plastic of its time, used for everything from buttons to scientific instruments to billiard balls to geegaws.” Oh, and up through the early twentieth century, binding, saddles, nuts, bridge pins and sometimes bridges and inlays on guitars.

Although mass production techniques allowed a few of those trinkets to reach the homes of the middle class, most came to rest in display cases of the more privileged in society. Some 1,200 of the more impressive of those baubles ascended to the top rung of the social ladder that is Buckingham Palace. Although the Royal Collection Trust contains a number of pieces carved in Medieval times from walrus and whale ivory, catalyzed by increased trade with Africa in 18th and 19th centuries, the bulk of the collection consists of works wrought from African elephant and rhino ivory.

Those curios of the rich and famous stablished an artistic and decorative aesthetic that not only survives, but continues to drive ivory trade. In essence, folks see the beautiful, old ivory works in museums and private collection, develop a yearning for something similar, and search for a vendor who in turn searches for a dead elephant. Sure, it’s possible to tranquilize an elephant and to leave the beast breathing after it yields its tusks. But, dead animals are more predictably compliant and it’s typically easier to kill rather than to sedate a large animal. So, execution is the poacher’s method of choice.

This economic model is especially apparent, observed National Geographic in its 2013 film The Economics of the Illicit Ivory Trade, in China where a 2,000 year old tradition has combined with the buying power of an emerging middle class to produce an all time high in demand for ivory. That demand in China and other Asian countries like Vietnam has driven the price of ivory to $60,000 per kilo, more the cost of gold or cocaine. The illegal slaughter of elephants now averages around 20,000 per year, a killing rate that National Geographic estimates will eliminate the African elephant from the planet in a decade.

In February 2014, forty six countries, including the US, convened for The London Conference on Illegal Wildlife Trade. The meeting resulted in the issuance of a declaration recognizing “the economic, social and environmental consequences of illegal trade in wildlife” and emphasizing in particular the threat to “the survival of elephants in the wild.” In response, the participating nations resolved to strengthen law enforcement, increase international cooperation, endorse the action of Governments which have destroyed “seized wildlife products being traded illegally,” and to raise awareness of the problem.

While the London group would raise awareness though conventional public education programs, the International Fund for Animal Welfare has suggested a more dramatic methodology: to offer “a token of support for elephants,” private individuals should destroy their ivory possessions. Prince William has joined the chorus by suggesting that the Crown lead the way by destroying those 1,200 royal trinkets.

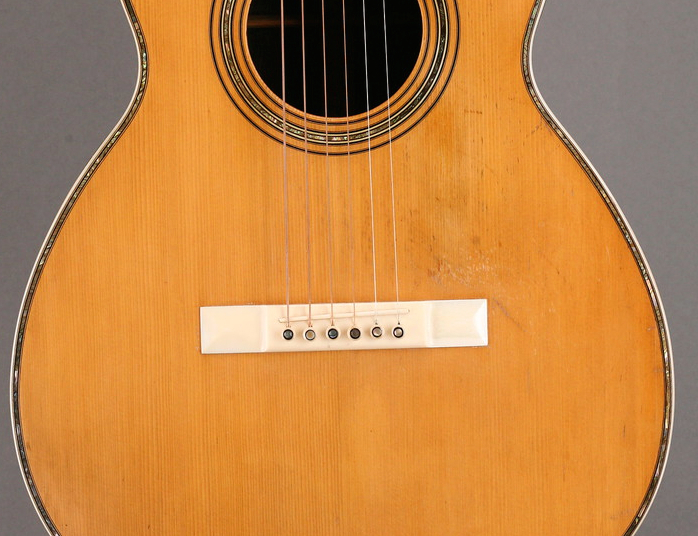

This 1905 Martin 00-45 has an ivory saddle set into an ivory bridge with ivory bridge pins. And the binding? You guessed it. Ivory.

The New US Law

Although the US has not taken up the mantel of the Princely proclamation, on February 11, virtually contemporaneously with the London Conference, the Obama Administration issued a National Strategy for Combating Wildlife Trafficking. The administration used ominous language in announcing its environmental call to arms:

In the past decade, wildlife trafficking—the poaching or other taking of protected or managed species and the illegal trade in wildlife and their related parts and products—has escalated into an international crisis. Wildlife trafficking is both a critical conservation concern and a threat to global security with significant effects on the national interests of the United States and the interests of our partners around the world

Echoing the London group, the Administration intends to address the crisis with a three pronged strategy of strengthening enforcement, reducing demand and building international cooperation. The Strategy is particularly focused on trade in elephant ivory and rhinoceros horn and assures that “nearly all commercial trade” in those substances “will be prohibited.”

So, nearly all trade in those ivory-bearing guitars will be prohibited in the US. If you own one of those instruments festooned with the “plastic of the 18th and 19th centuries” or are considering acquiring one, you might want to know what “nearly” means in this context. No sales? No importation or exportation?

As of this writing, we don’t know the specifics. In accordance with administrative law precepts, the governing agency, in this case the US Fish and Wildlife Service, will propose a regulation that will be posted for 90 days of public comment and then, potentially revised in light of the comments and if not withdrawn, will be promulgated as a regulation with the force of law.

What we do have at this point is the US FWS summary of what it expects to propose. In general, the proposal would ban the import of all raw ivory, except if you are importing a live elephant or, if the pachyderm who made the involuntary donation is no longer among the living, you killed the poor thing yourself. Really. Zoos can still import elephants and FWS has promised that its “administrative actions will not significantly impact the import into the United States of African elephant sport-hunted trophies.” So, hunters can kill up to two elephants annually and drag home their heads to impress the neighbors. (But, only if FWS reaches the counterintuitive conclusion “that killing the animal will enhance survival of the species.” )

“Ah,” but you say, “I’ve got all the elephants I need, living or dead. But I do have an old guitar with suspicious looking white stuff for binding, nut, and saddle. May I still keep the guitar without fear of FWS officials breaking down my door and grabbing the instrument?” Yes, legal possession will remain legal.

“But,” you add, “what if I want to sell it or maybe buy another to augment my collection of Civil War era Martin guitars?” Well, if that suspicious stuff is ivory, you’re going to have trouble selling it or buying a mate for it.

So, how to determine if that binding is real ivory and not synthetic ivoroid? If you’ve the time and money, you should contact Samuel Wasser, Director of the Center for Conservation Biology at the University of Washington. As reported by National Geographic in a 2013 article, A Powerful Weapon Against Ivory Smugglers: DNA Testing, by utilizing DNA analysis not only can Wasser distinguish ivory from synthetics, but he can differentiate among elephant, hippo, walrus, hornbill and sperm whale ivories. Better yet, if that stuff is African elephant ivory, Wasser and his team can pinpoint the location of the elephant who made the sacrifice for your guitar to a 160-mile radius. You could make a pilgrimage to the elephant’s homeland and erect a “a token of support” for him on the very spot where he yielded to the demand for the plastic of the day.

Not willing to part with your guitar long enough to have its DNA analyzed? You’re in luck if your guitar is a Martin. The company and its legion of fans have accurately documented the Martin ivory era. Prior to 1918, all Martins of style 28 and higher sported ivory binding. In addition, pre-1918 style 42 guitars featured ivory bridges.

Other early guitar manufacturers have followed similar though less well documented time lines, so you’ll have to hunt down your local DNA testing services or scour the Internet for information. While you’re Googling your way around cyberspace you’ll undoubtedly come across vendors offering nuts, saddles, and bridge pins made of, yep, African elephant ivory (as well as similar-looking ivoriod, bone and fossilized walrus ivory). So, even if the guitar that you wish to sell or buy is but days old, you’d still be wise to scrutinize those white parts.

This 1890 Martin 2-20 has ivory friction pegs.

Selling, Importing, and Exporting Guitars

OK, let’s presume that you either have or want a guitar that spots ivory parts. What’s the bottom line? According to FWS’s February 25, 2014 directive, two legal provisions apply.

Your guitar is exempt from the new regulation if it’s an antique.

First, your guitar is exempt from the new rules if it qualifies under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) as an antique. An antique is “not less than 100 years of age” and its ivory parts have “not been repaired or modified” after December 27, 1973 (the day before the ESA went into effect). And you, rather than the government, have the burden of proving that the guitar fits the exemption. You’ll have to supply the sworn statement of an “appraiser” because “Notarized statements or affidavits by the exporter or seller, or a CITES pre-Convention certificate alone, are not adequate proof that the article meets” the antique exemption. And the vintage guitar dealer you enlist to write a report must have “earned an appraisal designation from a recognized professional appraiser organization for demonstrated competency in appraising the type of property being appraised, or can demonstrate verifiable education and experience in assessing the type of property being appraised.”

Remember, too, that if those slots in the nut have been filed or the binding repaired in the past 100 years, the guitar loses its antique status and, presumably, the 100 year wait begins anew from the date of the repair. Or, you can simply swap out that nut for one made of something other than elephant ivory. You could also replace that ivory binding with ivoroid but a change like that won’t serve either the instrument’s aesthetic of its market value.

Provided that you can prove that your guitar meets the antiques exemption, you can export it to another country, even to sell it, but you can’t import it to buy it. You can sell it anywhere in the US, though.

Your guitar is exempt if you acquired it before February 26, 1976.

“But,” you say, “my guitar is old, but not that old. I do prefer guitars from the steel string era.” FWS has a second exception to the “nearly complete” ban on the commercial trade in ivory:

Orchestras, professional musicians and similar entities will be allowed to import certain musical instruments containing African elephant ivory if the instruments qualify as pre-Convention and are not destined to be sold. Worked African elephant ivory imported as part of a musical instrument will continue to be allowed provided the worked ivory was legally acquired prior to February 26, 1976; the worked elephant ivory has not subsequently been transferred from one person to another person in pursuit of financial gain or profit; and the item is accompanied by a valid CITES [Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species] musical instrument passport or CITES traveling exhibition certificate.

That reference to February 26, 1976 is to the date when ivory was added to Appendix I of CITES, the treaty’s most restrictive category. That “musical instrument passport” is a relatively new addition to CITES that provides a three-year, renewable and non-transferrable passport that allows the crossing of borders without the otherwise required import and export permits. Here’s a how-to guide to getting a passport for your guitar. Remember, though, that you can only get that passport if your guitar complies with all relevant CITES restrictions. So, that Brazilian rosewood bridge and Hawksbill sea turtle “tortoise” pickguard must have been acquired legally.

Let’s take a close look at the fine print. First, this exemption only limits imports. So, provided your guitar, whenever you acquired it, complies with CITES, you can take it out of the country. But, you’ll only be allowed to bring it back if you’ve owned it since February 26, 1976. Didn’t save that receipt? Remember, the burden is on you to prove that your guitar complies with the law. So, get a letter from the seller, preferably notarized, or leave that guitar at home.

OK, now what about your ability to sell an ivory-bearing guitar that you’ve owned since 1976? Remember, 100 plus year old “antique” guitars can’t be imported for sale, but can be exported for sale and can be sold anywhere in the US, though. The restrictions on non-antique guitars are much tighter. You cannot sell your guitar across state lines. Moreover, you can only sell your guitar within your own state, and only if you’ve owned it since 1976 and haven’t repaired the ivory parts. Your buyer won’t be able to resell it until it reaches 100 years in age. Presuming that you bought the guitar on February 26, 1976, the guitar won’t again be able to be sold until February 26, 2076, and then only if its ivory parts haven’t been modified in the century.

There are a couple of obvious loopholes here. First, you can simply replace the ivory parts, which will be easily accomplished if they consist of nut, saddle, or bridge pins. Second, if you’re desperate to sell or acquire a particular guitar, you could facilitate an intrastate sale by relocating to the state of the potential sale. That, though, would almost certainly require establishing residency in that state, which typically requires providing evidence of intent to live permanently in the state, demonstrated by indicia like home purchase or lease, auto registration, and voter registration. By doing so, you’d certainly set new standards for the symptoms of Guitar Acquisition Syndrome!

This 1890s W.A. Cole’s Eclipse banjo has a nicely engraved pearl man-in-the-moon, but as with most good quality instruments from this period, the nut is ivory.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is that if you are planning on traveling with or selling or purchasing an ivory-bearing guitar, you’ll need to educate yourself about these new restrictions. True, we don’t yet know all of the specifics, but FWS has outlined the policies in fair detail and it has stated that all of its “employees must strictly implement and enforce all” of the new provisions. Proceed with caution and, in the words of Joe South’s Walk a Mile in My Shoes, “you’d better be careful of every” step.

Alternatively, to show your solidarity with Prince William, you might also consider piling those Civl War-era Martin guitars in your front yard and setting them on fire. But, first check to see whether your community’s ordinances allow for open fires.

All photos courtesy of Frets.com.