Anthony Wilson is absolutely steeped in Old School. He’s been up to his eyeballs in the Great American Songbook occupying the guitar spot in Diana Krall’s band since 2002. His father, Gerald Wilson, was a luminary in the whole “West Coast” jazz scene. He has rubbed elbows with legends like Ted Greene and Dennis Budimir, played on records by Mose Allison and Diane Schuur, not to mention Sir Paul McCartney’s album of standards, Kisses On the Bottom. But he’s also stretched out, as a session player (see Joe Henry’s Fuse) and on his solo recordings, diving into Brazilian music (Campo Belo) and long-form compositions (Seasons: Song Cycle for Guitar Quartet).

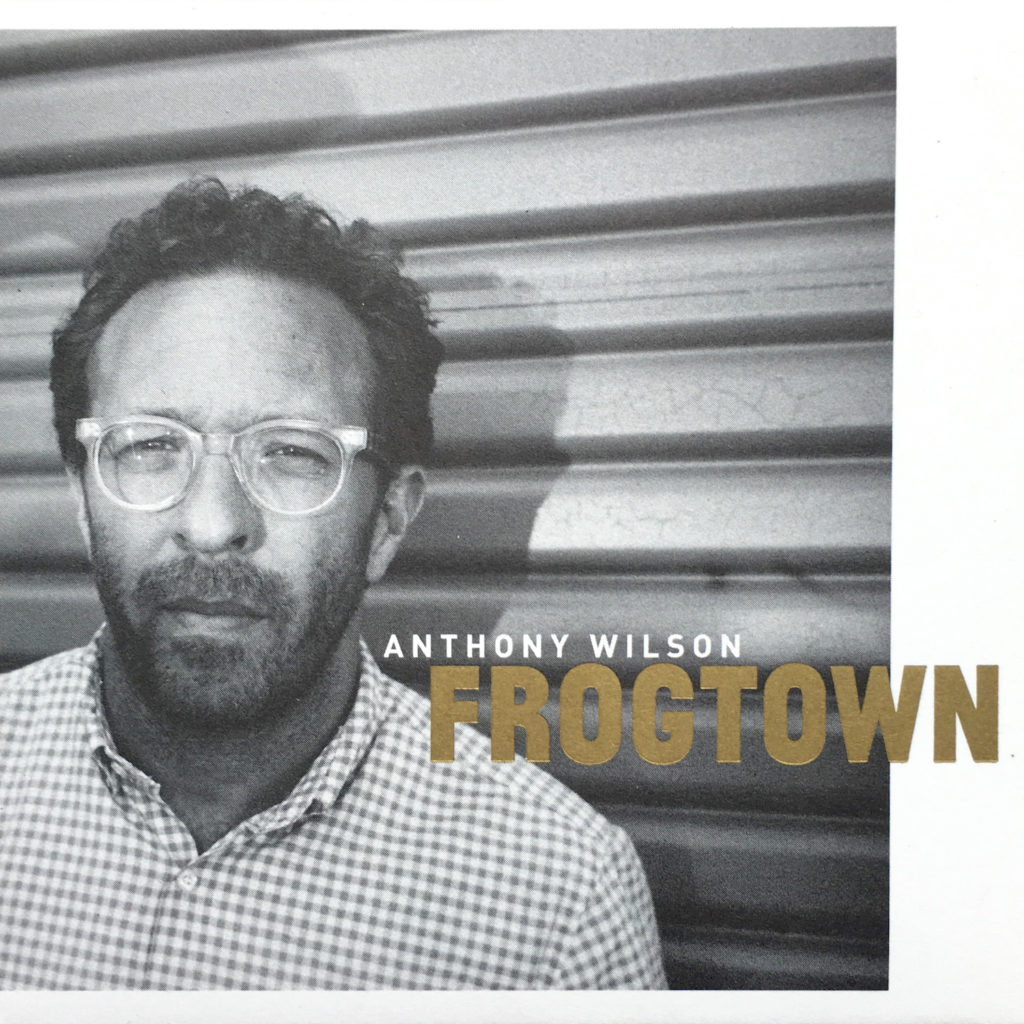

Under the circumstances, you wouldn’t expect to be surprised by a new Anthony Wilson record because you’re already expecting something different, and yet with his new album, Frogtown, Anthony does just that, delivering something akin to a singer-songwriter record, but one that’s redolent with his history – as a player, a singer, a composer, an improviser and a student of Jazz.

Anthony was kind enough to chat with us not once but twice, taking a break in Perth, Australia while on tour with Diana Krall and checking in again when he got home. The conversation went deep and wide, amounting to much more than a single web article could hope to contain, so we’re presenting it in two parts (and leaving out the discussions of wine, food and Japanese sneaker shops). In Part I: Making Frogtown we cover a bit of what went into making the record – the composition process, recording, influences et cetera. In Part II: Guitar Talk we get into the guitar geekery, talking gear, technique and, of course, nail care.

Part I: Making Frogtown

Fretboard Journal: I’ve read that a lot of what went into Frogtown developed as you played out with folks like Larry Goldings and Jim Keltner. How much of the album was “composed” and how much evolved through that process?

Anthony Wilson: Well, really, situations that I played in with different musicians over the past three years or so helped me to see what I wanted to do with my composing, and how I wanted performances to unfold and exist. The main thing that I started cluing into, playing with Jim Keltner, with Larry Goldings, with Patrick Warren, Mike Elizondo, Petra Haden, was this idea that, because I was starting with instrumental music, I had this intuition that I wanted to have songs that didn’t depend on the improvising for their existence. By playing with different people, who came from these different walks of life, who weren’t necessarily “jazz” players, so that their focus wasn’t on what they did with their solos. Of all those people that I’ve mentioned, I would say that Larry is the only one that you would consider to be, straight down the line, a “Jazz Man,” but at the same time Larry shares this feeling that I have, which is that the improvisation can provide context in a song, or it can provide texture in a song.

There are a lot of things that improvisation can do other than being solos, being something that becomes the focus of your attention when it’s happening. Larry’s got a compositional sense, or a sense of the song, and all of these other musicians… Keltner, that’s what he’s lived his life doing – he’s a born improviser, who came up most inspired by the jazz drummers of the day, but in his work he became a drummer who served songs better than almost any other drummer, ever. So there’s that sense that, “Oh yeah, we’re improvising, but we’re focusing on the song.”

That was where this all started for me, playing with people and seeing that we could get to something, even in instrumental music that was much more about delivering the song with our playing. That led to me trying many things with my writing, and one of the things that had been sitting there, kinda gnawing at me, was the fact that I wanted to sing again, after being in bands where I sang a lot, back in the day, throughout my teenage years and then stopping, then in these last four or five years going, “Wait a second, I’d like to sing again.” That seemed perfectly in tune with everything that I was feeling, because singing a song is about telling a story. That kinda created the track that I was going down, and all the music that I was listening to over the last five, seven years also put me down that track. And all my composing for anything that I did had to do with a real focus on the song, on creating a specific world in the song that we didn’t let go of just because there might be some improvisation, working on lyrics that could tell stories, working on my singing. Then, over time, playing with all these various musicians, it started to gel and come into focus, and that’s about the time that I decided to make the record.

FJ: How long was the composition process? When did you start writing these songs?

AW: I would say that the earliest song that I wrote that’s on this record is “She Won’t Look Back,” which is probably from 2014. We did sessions, playing shows with various people, shows at The Blue Whale in downtown L.A. that were kind of workshops for what I’d bring in. Once I thought I had a group of songs that was working, and a kind of a working ensemble, which is really the group of musicians that’s on Frogtown – Mike Elizondo being a really important part of that group of musicians because when he arrived, just because of his mentality, his sensitivity, his experience, both with hip hop and pop music production, as well as a session musician for so many people, and then a long-time previous association that he and I had, playing jazz, years and years ago…

FJ: I thought the connection was more recent, through Blake Mills or…

AW: Yeah. Much earlier, probably when I was in my earliest years of college and he was finishing up high school we got connected by a drummer named Trevor Lawrence in Los Angeles and we had a little trio. We played straight ahead jazz. We played a lot together, and then our paths diverged and I never even saw him. Then one night, Blake Mills put together a band to do one of the Mollusk Sessions [jam sessions at the Mollusk Surf Shop in Venice, Calif.], so he called me and he called Mike and he called Stuart Johnson… I walked in and there was Mike, and I was so happy to see him, I hadn’t seen him in so many years, and we played together that night and I said, “Man, we gotta start playing together on my shows as well.” As soon as that happened, it was like… it was the glue that put everything together. The songs started coming into focus about that time, which would have been springtime, 2015, we decided to go into the studio and I asked Mike to produce because I really felt that he would get it. I wanted every song to have a sonic identity, a musical identity, and he’s such a great producer, so great in the studio, but he never overworks thing, so we wouldn’t run into a situation where we were going too far with the songs. All of the songs are early takes, things that are overdubs tend to be the first take. Mike is real good at knowing, “OK, you got a great take. Let’s go a little further…” but once the idea is starting to get a little old and tired he never overworks things.

I knew that it would be like that with him in the studio, so that’s about when we decided to go and do it. For me, everybody that I play with it’s a pretty personal connection. I’ve known him for so long, so it’s kind of coming full circle, actually, which feels really great. For me to play with somebody I have to have that very personal thing. I think that putting together a band is that delicate of a thing, especially if the intention is to really render the songs the way that I intended them as a composer. One of the choices that could seem arbitrary is to call Charles Lloyd to play on my album, but it’s the least arbitrary thing, it’s the most family decision, because that song [“Your Footprints”] is really about legacy, it’s about ancestry, and it’s all about this idea of continuity and how we feel that in our lives as musicians. Charles was very, very close with my father, and I’ve known Charles for many years. As soon as I sat down and spent an afternoon writing that song with Dan Wilson [no relation], we made a little demo of it, and all I could do was hear Charles’s voice in that song. It was so much an idea that he stands for – one of the things that Charles likes to talk about is this idea of, as musicians we are “standing on the shoulders of giants.” The only reason we can have any kind of perspective, that our music can advance, is because of the perspective that we’ve been given by these masters that came before. As soon as the song was written, I was like, “This is Charles. He needs to be here with us.” And Petra [Haden], we went to high school together, so I’ve known her since I was in my teens. All of these players have given me something really personal, and, to make an album, that really helps me to do it.

Anthony Wilson and (a few of) The Curators: (Clockwise from Upper Left) Anthony, Patrick Warren, Matt Chamberlain and Petra Haden.

FJ: Where’d you record the album?

AW: Can Am… Back in the day (we’re talking, like, in the ‘90s) it was the headquarters of Death Row Records. It was a hip-hop studio, which I think is kinda awesome. Suge Knight, so Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Tupac, all these people were on that label, and this was kinda the house studio. Back in those days it was kinda rough, but I think Mike made the connection with the studio through Dr. Dre. It changed ownership, and Mike has a long-term lockout on the main room there because he does a lot of production and A&R for Warner Brothers, so it enables him to have a workspace. It’s a great room – it’s got a big live room which is great for drums, it’s got several isos. And Mike is a crazy, crazy collector of gear – everything from pedals to amps to vintage keyboards, guitars, basses – and basically his entire collection of gear is just there.

FJ: Sounds like it’s basically Mike’s home-away-from-home…

AW: It’s like you’re going to someone’s home, but it’s a real room, you know?

We did it in two sets of sessions, and then subsequent overdubs. We got the basic group in twice for about three or four days at a time, and then when I needed to put on any extra guitar overdubs, or a couple keyboard overdubs, or anything that Petra needed to do, we did those in separate days. Mike said, “Hey man, there’s a week open now at the studio. Do you think you can get Jim [Keltner] and Patrick [Warren] in the room and we’ll do the first sessions, see what we can get done.” And that’s how we did it. We piled in there for a few days, it’s a great room and everybody felt comfortable and he felt comfortable, because it’s like home and he really knows the space. Like, when Patrick was looking to… process the B-3 in a certain way, Mike was able to grab a few boxes and rig it up real quickly. So it worked out really well, and Mike was cool about, “Oh, you wanna try that guitar? Go ahead.” Everything was really well-maintained, all his guitars are really well-setup and all the amps – actually, Austen Hooks has been going through all the amps that Mike has, making sure everything is perfect, and that’s a lot of amps.

Mike Elizondo (left) and Patrick Warren dial in a bit of processing for the B-3.

Luckily, we’d all played the songs from the record at live gigs and had a sense of how they went, and how I wanted them to go. So when we got into the studio it was mostly: make the arrangements as tight as possible and go after something sonic that could really make the song be what it needed to be; that was really important. We didn’t spend a huge amount of time on any one song – we would do a take, two or three at the most. On “She Won’t Look Back” we started out by making a drum loop – Jim made a loop and then Mike put that through some kind of strange… basically sort of degraded the loop – and we used that as our basic rhythm, but when we played the song, once we’d recorded the loop, I can’t imagine that we played it more than twice. Jim can sometimes say, “Ah, let me try it again because I’m not quite getting what I want,” but Jim is so smart, he knows if he does something more than about three times, even if he starts to get to a part that feels more consistent something is in danger of getting lost. And Mike was also very cognizant of that, so if Mike trusted that we got it then he would never say, even, let’s try it again. It made for a good way of working.

FJ: What about working with Charles Lloyd?

AW: The way we made that one, it’s just one guitar track and it’s all done live except for Charles’ saxophone and my vocal. I knew from the first that I wanted Charles to play on it, but it took a while to find the timing when he could come, because he’s, like, on the road forever. I wasn’t really sure how it was going to work, because I didn’t have him to play off of… so he came in and, basically he did three versions of the song – he played it through, straight through three times, and we used pieces from two of his takes, which were wildly different, so we used the ones that were most integrated with what was happening. He was amazing; he said, “I’m just going to surrender myself to what’s there.” That’s why, I think, it works. He’s got this great sense of presence while he’s playing. It was amazing to see. He asked me a couple questions about the chords – we went to the piano and he said, “How’s that one voiced?” And that was it. Three times through and we were done.

FJ: A lot of your playing on the album might seem almost unexpected for folks who are familiar with most of your work, both as a solo artist and with Diana Krall. How much of that was dictated by the composition or by the instrumentation – not playing an archtop as much, in favor of a Tele, or a Les Paul, or a flattop?

Anthony stumbled upon this Kay archtop (vintage unknown) at the studio and ended up using it on the song “Occhi di Bambola.”

AW: Well, in the same vein, I wanted to play in a way that would serve each song the best. We didn’t spend huge amounts of time working on tones or trying lots of different things. If we found something that worked quickly I would stick with it. On “Occhi di Bambola,” Mike had this old Kay archtop, when I tried that, it really kicked in. A lot of the acoustic parts are a 1955 J-45 that had a beautiful chunkiness to it, a great bottom end, but clarity, so, a lot of the acoustic parts, I was just loving that guitar so much in the studio. I’ve got a Japanese Guyatone, and a Kapa Continental that I put some different pickups in and used those on a couple things, and an old, ‘50s Tele that Mike had on “Cares of a Family Man” and “Frogtown” – it had a nice bite, just beautiful presence within a track, and for the kind of lines that I wanted to play it seemed to work very beautifully. So, if a guitar could speak within the song, I used it. It was really about giving a voice to the song, so if some kind of simple slide part needed to be played, I played it.

As far as the playing itself, I feel that there’s a lot of things that people haven’t known about me for a long time – about the music that I’m interested in, and what I care about, and what my background is. I think, at a certain point, when I started to get known to anybody I was pretty much playing instrumental jazz. That’s how people came to know me, so far, but as any friend who comes to visit my house will tell you, we definitely don’t only reach for instrumental jazz albums. That’s been my life – I have a mom who listened to every kind of music under the sun, from Indian music to classical music to folk music to jazz to, you know… so much stuff. I’d say that it’s her openness to music – because I wouldn’t say that my father was very open to anything except jazz, that’s where he lived. As a child growing up in the ‘70s, being into all of the bands that were popular during that time, rifling through my mom’s record collection, and hearing the radio, all of that stuff became who I was as a musician.

FJ: It was kinda hard being a jazz fan in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

AW: Yeah, definitely. It was an odd period. Having a father who was a jazz musician, I know how he struggled at that time. A lot of musicians were in that same boat.

Now, when I meet teenage students, kids who are in high school or just starting college, because of the technology, the availability of music… what people have been able to access and hear in the jazz world is so much wider than what was available to me in 1983 or ’84 when I first started to be really interested in jazz, and really want to learn how to play it and dedicate a great deal of myself to knowing what it was. Gosh, you’d really have to be digging in order to find a lot of the things that very young people today already know about. When I was in middle school and high school I was one of maybe three or four people that I knew that had any interest in the music. That really, truly has changed. If you go to clubs in New York, or Los Angeles, all around you will see young people in the audiences. That just wasn’t the case.

Just to finish the thought, so much of all that I listen to informs my playing. Even my jazz playing is not typical. The players that I’m interested in, and have been interested in are a little bit different. I’ve always been interested in people like T-Bone Walker and Grant Green, or Billy Butler or Bill Jennings. Definitely I liked people like John Scofield and Pat Metheny growing up, but I would never really consider them foundations of my playing style. So even my jazz comes from, someplace a little bit different. I guess what I want people to know about me as a player is that, if I’m unique in any way it’s because what I’ve been drawing from is much different. And then there’s all these other things in the background from other styles. I would say to anyone hearing this record that you’re getting a much more well-rendered picture of what kind of player I really am, and all the things that inform it.

FJ: What about your singing? What influences would you cite there?

AW: I just feel like such a beginner again in the world of singing. I feel like I don’t even want to presume. What I like in singing is a sense of intimacy and honesty. I don’t like affectation in singing. There’s just so many singers that I like… All I wanted to do was give a voice to these stories. All I could think about during this process over the last couple of years, trying to get my voice open and out and into the music was this idea that, if I could sing in what feels like an honest way, without trying to be too singer-y, I would be happy. If I could achieve some sense that, when you hear the song, I’m kinda talking to you. There are just so many singers that I love… If I say that Willie Nelson is a favorite singer it’s just because of that beautiful way that he has with a conversational tone and a way of connecting. Rather than calling out influences I’d just say that if I could ever get to speak and have my voice communicate a song in that way at some point in my life, I sure would love it.

FJ: I half-expected you to mention the Mose Allison record you played on…

AW: Oh, he’s just an influence for me in everything. In fact, I would say something like that song called “I Heard It Through the Skylight” is, in some way, my attempt to inhabit the same kind of world that he’s in. Mose Allison’s one of my favorite artists ever. There’s just something so natural about him and, whether he’s singing his own original songs or whether he’s singing traditional blues songs, it’s something so natural, conversational. It’s not overworked. And there’s this beautiful sense of the blues that he has. That kind of talking blues approach in “I Heard It Through the Skylight” kinda comes from things I heard Mose Allison do, for sure.

Probably none of it was linear. I wrote that song starting as a little exercise because I had been listening to a bunch of Harry Nilsson, as if I could ever sing like Harry Nilsson. There is only one person who could do that and that was him, what an incredible artist, writer, singer… just presence in music.

I loved how Harry Nilsson in his songs used dominant 7th chords, and I realized that people are really afraid of dominant 7th chords these days – they don’t really use them, they tend to use more oblique chords. Dominant 7th chords tend to want to resolve, to go someplace. People want to use chords now that don’t go anywhere.

It’s like a thing, if you do that you’re sort of reaching back to an older form of harmony and another kind of connection to another kind of music. I don’t mean people in forms of music that are playing blues-related music, or folk-related music, where they use dominant 7th chords and it’s just a thing, but in popular music and in jazz… one of the strangest things to me in jazz right now is how afraid people are of a kind of an older form of functional harmony.

So this was kind of a digression, but going back to that song, I was listening to all these songs that Harry Nilsson would do and he would have dominant 7th chords that, sometimes they were resolving, or they would just move in different ways. It was a great sound, so I said, let me try to work with some of this, see if I can get a song that uses mostly exclusively dominant 7th chords, all kinda 6th chords and 6/9 chords, that has that kind of motion. It turned into a kind of talking blues song, which I was really happy about, so when you say Mose Allison, I guess all I can say is that’s definitely something that I used to hear him do on all those classic Atlantic recordings. So, I guess that’s in there, somewhere.

That record that we did, that Joe Henry produced – I only play on a couple songs, but the day that I spent there… I mean, he’s an improviser all the way, but the songs always retain the identity. He’s so much about the song, except he’s the most free piano player, the way he can solo and the language in the solos and his improvisation is just startling. It’s just, my god, it puts goosebumps on you, he’s so adventurous and still so based in the blues and the roots of the music.

BONUS:

Anthony invited us to premiere this video of a new song – “While We Slept” – performed live, solo:

Check out Part II: Guitar Talk.

For more information about Frogtown check out Anthony’s website.